Forum on China-Africa Cooperation: Beijing’s Blueprint for Foreign Relations or Sui Generis?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 23

By:

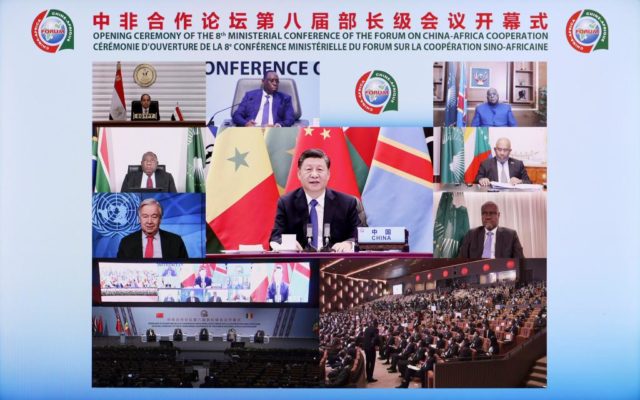

The triannual Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC, 中非合作论坛, Zhongfei hezuo luntan) convened in Dakar, Senegal this week (Xinhua, November 29). This year’s meeting was held at the ministerial level, a departure from the last two fora, which were leader-level summits. More African heads of state, 50, attended the 2018 FOCAC meeting in Beijing than the UN General Assembly that year. The summit was a particularly successful moment for President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy as he welcomed three new participants — Gambia, Burkina Faso and Sao Tome and Principe that had recently switched their diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) leaving Taiwan with only one diplomatic partner in Africa, Eswatini (Xinhua, September 3, 2018; FOCAC 2018). This year’s meeting occurs at a more difficult juncture for China and many African states with countries in Southern Africa facing fresh travel bans following the emergence of the Omicron variant, and China limiting its foreign investment as it focuses on economic challenges, including ballooning debt, at home.

Despite the different atmospherics surrounding FOCAC 2021, the scaled-down version of the meeting is due to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, and is not the result of any noticeable depreciation in relations between China and African states. Xi addressed the opening ceremony virtually, with many African leaders watching via videoconference, as Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with counterparts from 53 African countries in Dakar (Xinhua, November 29). This continued high-level of official participation indicates that FOCAC still carries great significance for many African countries and China, where the China-Africa relationship is hailed as a “model for South-South cooperation” (南南合作典范, nan nan hezou dianfang) (Guangming Daily, November 19).

A Framework for China-Africa Relations

The PRC uses FOCAC to institutionalize and provide a strategic framework for its engagement with Africa. At the 2018 summit, Xi launched eight major initiatives: industrial promotion, infrastructure connectivity, trade facilitation, green development, capacity building, health care, people-to-people exchange, and security (Xinhua, September 3, 2018). Some of these efforts have weathered the impact of COVID-19. For example, China-Africa trade volumes are at their highest level in history amounting to $185.2 billion over the first three quarters of 2021 (Xinhua, November 17). China has also pushed through with the establishment of ten Luban Workshops, which seek to boost local African capacity through technical and vocational education training programs (China Brief, November 5).

Other areas, particularly people-to-people exchanges, have been stymied by the deleterious impact of COVID-19 on international travel. For example, in 2018, Xi stated “more African countries are welcome to become destinations for Chinese tour groups”, which is how many Chinese travel overseas, but tourism flows from China have largely dried up during the pandemic (Xinhua, September 3, 2018). For example, in 2020, travel from China plunged by 87%, and has only recovered to a fraction of pre-pandemic levels (Reuters, November 22).

China’s economic reorientation may also be affecting its investment in African countries through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China investment in energy and infrastructure projects in Africa has declined by around 70 percent from a peak of $11 billion in 2017 to $2.8 billion in 2019, and $3.3 billion in 2020 (Baker McKenzie, April 29). The decline, underway well before the pandemic, indicates China’s appetite for investment in Africa may be waning. China has also vigorously denied recent speculation that it might take possession of Entebbe airport in Uganda due to Kampala’s failure to meet stringent conditions for loans provided by the China Export-Import Bank, which if true, would contravene Beijing’s mantra that Western allegations of “debt trap diplomacy” are completely groundless (VOA, November 29; CGTN, November 30).

China-Africa Relations and Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy

China derives tangible diplomatic, economic and security benefits from its engagement with Africa, but there is also an important normative and global governance element to the relationship. The PRC State Council recently released a new white paper, which coincided with FOCAC, entitled “China and Africa in the New Era A Partnership of Equals” that lays out the core principles of China-Africa relations, highlights recent successes of the relationship, and provides a roadmap for future cooperation (State Council Information Office (SCIO) , November 26). The principles that the PRC attaches to the China-Africa relationship are drawn from its emerging foreign policy canon-“Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy” (习近平外交思想, Xi Jinping Waijiao Sixiang), which is a synthesis of the principles advanced by Xi on the conduct of international diplomacy and global development since 2013 (FMPRC, November 26). Taken together, these concepts present an alternative, Sinocentric model for the international system. For example, per the white paper, the first principle of China-Africa engagement is “amity, sincerity, mutual benefits and shared interests,” (真,实,亲,诚, zhen, shi, qin, cheng). This term was originally used by Xi in his October 2013 address at a symposium on diplomatic work in neighboring countries, and has since been enshrined as a guideword for China’s preferred form of relationships with friendly countries in the near abroad and Global South (China News, October 10, 2014).

Establishing strong relations with the Global South is a central pillar of Xi’s emerging vision for a global order- centered on a “Community of Common Destiny” ( 人类命运共同体, renlei mingyun gongtongti), which China has sought to translate from aspiration to reality through BRI and corresponding programs (Xinhua, March 24, 2020). In practice, the “Community of Common Destiny” provides a normative paradigm for China’s efforts to bring about a loosely hegemonic, Sino-centric international sub-system that is largely centered in the Global South (NBR, January 2020). In this emerging order, China’s interests are afforded pride of place, and participating states are required to demonstrate at least pro forma obeisance to Beijing.

A China “Model for World Development and Cooperation”?

China has long celebrated its special relationship with African countries. In his FOCAC keynote, Xi stated that “over the past 65 years, China and Africa have forged unbreakable fraternity in our struggle against imperialism and colonialism, and embarked on a distinct path of cooperation in our journey toward development and revitalization” (FMPRC, November 29). However, Xi has departed from his predecessors, in promoting China-Africa relations as “a shining example for building a new type of international relations”, i.e., a model for China’s relations with other regions and the world (Xinhua, November 26, 2021). By contrast, in his 2006 FOCAC address, President Hu Jintao celebrated China and Africa’s “major contribution to the advancement of human civilization”, but did not explicitly cite the China-Africa relationship as a model for world affairs (Xinhua, November 4, 2006). The new White Paper also cites China-Africa relations as “an Exemplary Model for World Development and Cooperation” that will set “an example by increasing the wellbeing of humanity, creating a new type of international relations, and building a global community of shared future” (SCIO, November 26).

In recent years, China has sought to create new institutions, or revive old ones, along the lines of the FOCAC that could best be approximated as “China plus many” [with China in the center] in order to promote alternatives to traditional international institutions, which Beijing sees as dominated by the West (National Interest, September 4, 2018). In contrast to formal US alliance systems, these regional groupings contain networks of strategic partnerships with titles that denote varying degrees of amity. For example, China-Russia relations, which amount to a de facto entente, are designated as a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for a New Era, the top tier of partnership in the PRC’s hierarchy of foreign relations (MERICS, August 24). A rung down are “all around strategic partnerships” with countries that China has cordial and productive relations, for example this term was applied to China-Germany relations in 2014 (MFA, March 29, 2014). Finally, a strategic partnership, which is the most widely used designation, denotes relations with countries that China cooperates with, albeit sometimes selectively on international issues, and has been used for relations with a wide range of countries from Brazil to Sudan to Ukraine.

Apart from FOCAC, China’s success in creating, viable Sinocentric multilateral institutions in other regions has been marginal. The 16+1 initiative between China and Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries has lost momentum. Enthusiasm among CEE states for deepening ties with China has waned as Chinese investment pledges have not fully materialized, and concerns over China’s political interference, and human rights record have heightened. Lithuania left the group in May calling it divisive, and to Beijing’s chagrin, has subsequently deepened its ties with Taiwan (Politico EU, May 21) As China has lost ground in the region, Taiwan has found willing partners in its quest for greater international space, which was highlighted by Foreign Minister Joseph Wu’s visits to the Czech Republic and Slovakia in October (Taiwan News, October 28).

The Shanghai Cooperative Organization is an important vehicle for China’s engagement with South and Central Asia, but lacks the Sino-centricity of FOCAC or 16+1 due to the presence of Russia, which is still a major player in the region, and now India. Likewise, the ASEAN-plus China dialogue is a key part of China’s engagement with Southeast Asia. China certainly has influence in ASEAN, including through proxies such as Cambodia, but Beijing has no hope of formal membership to say nothing of advancing a Chinese alternative, which would fall flat given the centrality of ASEAN to regional diplomacy.

These limitations indicate that for Beijing replicating the success of FOCAC outside the African context is increasingly unlikely. Nevertheless, under Xi, China is likely to remain undaunted in its push for a “new type international relations.”

John S. Van Oudenaren is Editor-in-Chief of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, please reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.