Further Rapprochement in Russo-Chinese Relations? Opportunities Versus Roadblocks

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 74

By:

Russian President Vladimir Putin is scheduled to visit China for a summit in May. In advance of that meeting, Russian sources are again claiming that an agreement on a gas pipeline will be reached between Gazprom and its Chinese partners. Allegedly, both sides have agreed to the pricing formula and the volume of deliveries, though the actual price has yet to be decided. Russia will apparently supply gas from the Kovykta and Chayanda gas fields in Krasnoyarsk Kray. Clearly the prevailing tone here is optimism that China cannot do without Russian gas and will sign an agreement with Moscow. But there is also an implicit acknowledgment that due to the tensions with Europe over Ukraine, which are even greater than many assume, Gazprom needs to intensify its Eastern Gas program—something it has not hitherto done (Interfax, March 27).

However, this is a familiar refrain (Interfax, January 22), and there is still no sign of a final agreement with China. Nevertheless, there can be no denying that even before the Ukraine crisis, Moscow was trying to reorient its energy exports eastward—but with little success (see EDM, March 13, 2013; China Brief, November 7, 2013). Neither can it be said that all is well in the broader economic dimension of the Russo-Chinese relationship. Zhang Di, the minister-counselor in charge of foreign trade at the Chinese embassy in Moscow, said that China’s imports of Russian machinery were unjustifiably low. Moreover the Russo-Chinese chamber for promoting bilateral trade in machinery and innovative products has “yet to produce tangible results,” suggesting that perhaps such a low volume of imports must either be limited by uncontrolled economic factors, or there may be more problems in this bilateral trade relationship than is generally admitted (Interfax, March 26). Indeed, Zhang said that Chinese companies are actively entering the Russian market to open their own production facilities, a sure sign of the non-competitive status of Russia’s firms (Interfax, March 25).

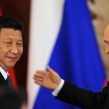

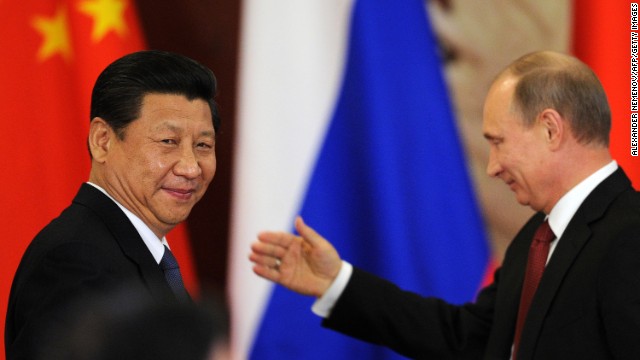

Clear strains persist in the political sphere as well. Both Putin and Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu have thanked China for their support of the Ukraine invasion and annexation (kremlin.ru, March 18; Interfax, April 1). But China’s government did not technically support it, although many experts did so in the press. In fact, President Xi Jinping told European audiences that China could not take sides. Moreover, it is clear that Russia’s entire Crimean annexation operation, from start to finish, created considerable anxiety in Beijing. Such policy precedents undermine the cardinal points in Beijing’s foreign policy arsenal concerning non-intervention in other sovereign states’ domestic affairs, the inadmissibility of foreign interest in Xinjiang, Tibet and Taiwan, as well as opposition to referenda, etc. (South China Morning Post, March 14; Reuters, March 28). So there are those in China who are clearly unhappy about what has been transpiring in Ukraine over the past several months.

To be sure, there are also those who want to use this opportunity to upgrade bilateral economic ties. Yu Zhangsheng, the chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, duly called for enhanced Sino-Russian cooperation in the international Association of Economic and Social Councils as well as in similar institutions (Xinhua, March 31). Yet, such initiatives pale in comparison with Russia’s other potential trade considerations. In fact, Putin, along with much of the Russian elite, appears convinced that Russia cannot afford to give up any leverage anywhere in the Chinese market—including with regard to high-performance weapons. So it is likely that China will receive such weapons from Russian manufacturers, or at least an announcement of such a sale is likely during the upcoming summit (Kanwa Defense Review, March 1). But even more compellingly, Moscow views its political relationship with Beijing as stable and beneficial—two characteristics that cannot be similarly applied to its ties with Washington (Kanwa Defense Review, March 1, 2014)

Finally, even despite its misgivings about Russia’s Crimean actions, Beijing stands to gain from any shift in Russian priorities to Asia, be they economic or political. Notably, the Crimean crisis appears to have created a major roadblock to the ongoing rapprochement between Tokyo and Moscow (see EDM, February 24), and China will undoubtedly be ready to pick up any slack in Russian energy exports and arms sales deriving from Western sanctions. But at the same time, the failure to generate an economically satisfying Russian agenda owes much more to Moscow’s failings than it does to Beijing’s shortcomings. After all, there is no compelling reason for China to buy inferior Russian goods when Russian bureaucratic obstructions and obstacles to reforms merely add to Russia’s economic dependence on China. And this dependence may well grow in the future and add to an already considerable dependence. Worse yet from Russia’s standpoint, if its rapprochements with Japan fails and if Moscow is isolated in the West, can it really say it is conducting an independent great power policy in Asia?