Hizb ut-Tahrir on the Rise in Bangladesh

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 23 Issue: 6

By:

Executive Summary:

- Since the ouster of Sheikh Hasina in August 2024, the banned Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir Bangladesh (HTB) has taken advantage of weak interim governance to openly campaign for its legalization, as well as stage protests and recruit among students, professionals, and elements of the security forces. The group poses a growing long-term threat to Bangladesh’s stability.

- HTB’s appeal lies in targeting high-achieving youth disillusioned with secular values, while cultivating links with military officers and bureaucrats to push its agenda of establishing a global caliphate. Although branding itself as nonviolent, HTB’s ideology has served as a pipeline to more violent jihadist groups.

- The group’s resurgence has been marked by propaganda campaigns, covert seminars, and large mobilizations like the “March for Khilafot” earlier in 2025, which drew thousands to Dhaka’s main mosque. These activities underscore its capacity to operate in the “gray zone” between politics and extremism, challenging state control.

- There are hundreds of trained members unaccounted for after prison breaks in 2024, and sympathizers are known to be in elite positions within Bangladesh’s interim government.

Since the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime in early August 2024, there has been an increase in activities by the banned group Hizb ut-Tahrir in Bangladesh (Bangla: হিযবুত তাহরীর বাংলাদেশ; the organization’s Bangladeshi chapter is referred to as HTB). Taking advantage of a dysfunctional administrative and law enforcement system, HTB began conducting political-religious activities openly, and demanded its name be removed from the list of designated terrorist groups (Prothom Alo Bangla, September 9, 2024). The Islamist group exploited the fragile state of the new Bangladeshi interim government to hold public seminars, appeal to remove its proscribed status, and engage in recruitment. These HTB activities primarily utilize online and in-person “gray zone tactics” (neither clearly legal nor illegal) that exploit the interim government’s weak and indecisive posture.

HTB’s Inception and Proscription in Bangladesh

Hizb ut-Tahrir (Arabic: حزب التحرير, “The Party of Liberation”; HT) is a pan-Islamist political organization founded in Jerusalem in 1953 that frames itself as a vanguard that seeks to bring about a unitary Islamic caliphate (For more on Hizb ut-Tahrir, see Terrorism Monitor, December 27, 2006). While HT frames itself as “revolutionary but nonviolent,” its doctrine is openly subversive, and Hizb ut-Tahrir is sanctioned in numerous countries—including nearly the whole Muslim world, and Bangladesh in 2009—on grounds of incitement to violence and radicalization (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, accessed September 16).

The organization’s Bangladeshi chapter, HTB, began in the 2000s with initiatives by several teachers from Dhaka University and Rajshahi University. The group was formed to establish an official HT presence inside the third most populous Muslim state in the world as well as work toward locally promoting HT’s global agenda of establishing a caliphate. To signify this ambition, Bangladesh was also designated as a wilaya (Arabic: ولاية, “state, province” of the prospective caliphate). Later, HTB spread its activities into the elite Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) and other major private universities like North South University (NSU) (Bangla Tribune, October 5, 2024).

HTB primarily targets, radicalizes, and brainwashes high-achieving students by tapping into the dissatisfaction of Muslim youths with the infiltration of Western-style secular and democratic values in Bangladesh. The group appeals to educated but conservative audiences by advocating the return of a caliphate in a similar form to the Ottoman Empire (Bangla Tribune, October 5, 2024; S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Commentary, April 25). The group was banned in October 2009 with a press note stating the organization was a threat to “peace, discipline, and public security” after former autocrat Sheikh Hasina came into power (BBC News Bangla, September 13, 2024). [1] HTB’s leader, Mohiuddin Ahmed, was kept under strict surveillance and later arrested in April 2010. [2] Since 2010, the group has moved underground, making occasional headlines in the media as a threat to national security.

In 2012, the Bangladesh Army shocked the nation when it announced in a press conference that it had foiled an attempted coup planned by mid-ranking officers and forcibly retired any army personnel linked with HTB (S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Commentary, February 7, 2012). It was not exceptional for HTB to infiltrate the army—the group has formerly attempted to incite officers of the Bangladeshi Air Force to overthrow the government following the Pilkhana Massacre (referring to the crackdown on a mutiny by the Bangladesh Rifles in 2009), a major contributor to its 2009 ban (BBC News Bangla, September 13, 2024). [3] HTB also arranged online seminars just before the 2024 national elections, which specifically targeted military officers. Interestingly, a faction of HTB’s leadership and members find Islamic-nationalist rhetoric more appealing than the pan-Islamist solution of a caliphate, which has generally lacked support in the country (S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Commentary, February 7, 2012). This particular faction repeatedly attempts to incite military officers to join their cause, claiming that they would end Western and Indian conspiracies against Bangladesh (Hizb ut-Tahrir Central Media Office, January 6, 2024).

HTB’s Covert Activities After Ban (2009–2024)

From 2012 until August 2024, HTB’s modus operandi was mainly based on indoctrination, infiltration, and recruitment. This included social media campaigns and targeted efforts to influence state institutions, including Bangladesh’s security forces. HTB’s main target was educated youth and established professionals in various fields, including academics, doctors, engineers, active and retired bureaucrats, police, and military personnel. HT broadly is notable for not advocating force or terror to achieve its goals. In its own words, it seeks to “overthrow governments through nonviolent means” in the countries where it operates (Wilson Center, August 7, 2012). Conversely, the group’s ideology easily serves as a pipeline to jihadism. This can most easily be seen in instances where al-Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates recruited HTB members, suggesting they see HTB as a potential recruitment pool (S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Commentary, April 25).

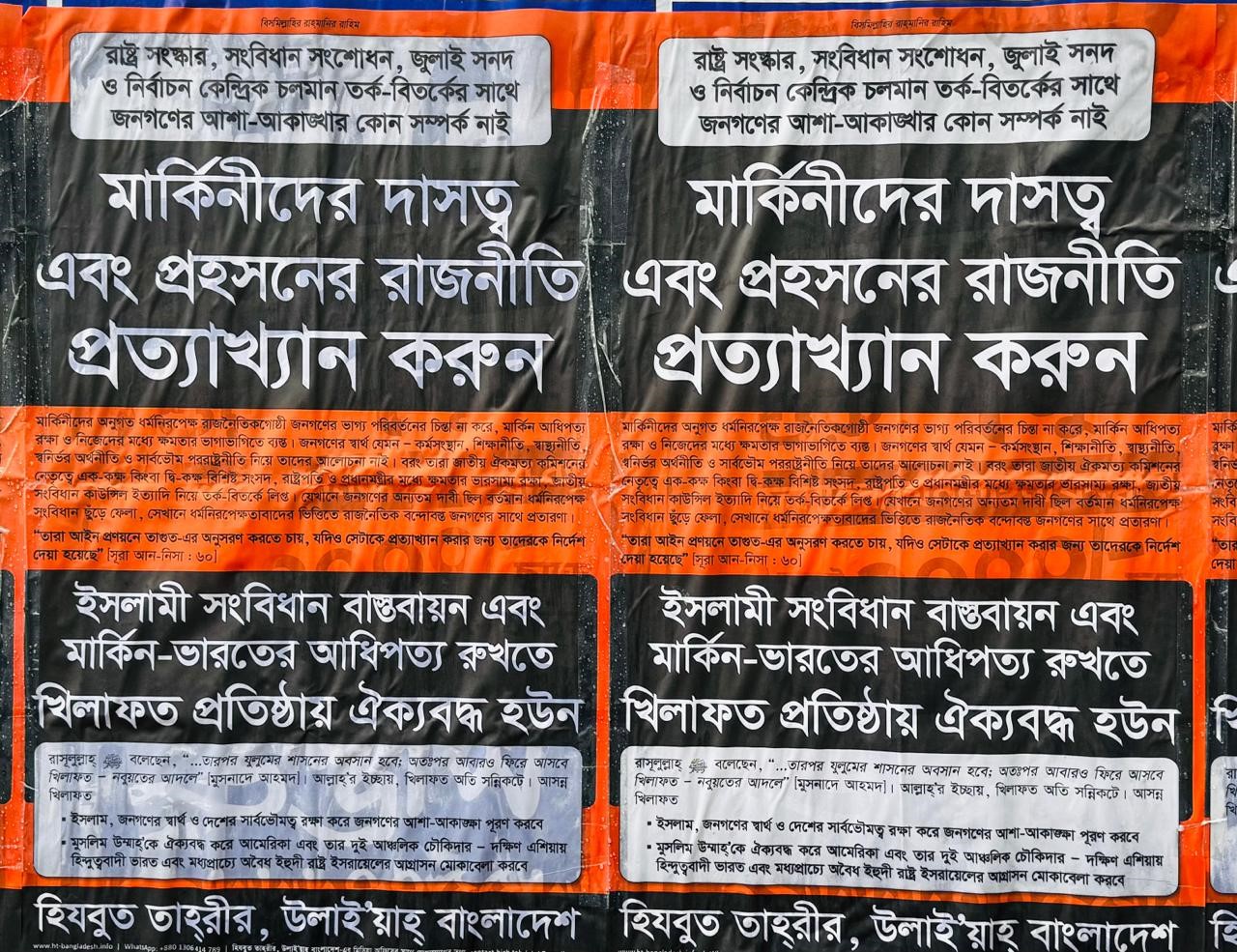

As of 2022, among HTB’s 10,000 to 15,000 members, there were 10 secret study groups of HTB where members gathered and discussed developments related to the Middle East, South Asia, and the West. These study groups used various books to suggest occurrences of torture, persecution, and abuse of Muslims all around the world (Ittefaq, October 30, 2022; Desh Rupantor, March 11). Recruitment likely increased after the fall of the Hasina regime in August 2024, with HTB promoting its goals by postering slogans in support of a new caliphate throughout Dhaka under the cover of night (Bangla Tribune, October 25, 2022).

In 2023, the Bangladesh Police’s specialized Counter Terrorism and Transnational Crime (CTTC) unit captured Touhidur Rahman Sifat, a Dhaka University graduate and freelancer. Sifat was the principal speaker in HTB’s online sermons and the mastermind behind the late-night postering (Prothom Alo Bangla, December 8, 2023). In addition, in early 2024, the group even mailed BUET students asking them to join its cause against “westerners.” HTB’s access to the list of student mail addresses exposed the extent of its infiltration of the administrative system of Bangladesh’s topmost engineering school (Daily Sun [Bangladesh], April 5; BBarta24, April 6, 2024).

HTB’s Activities in Yunus-Led Interim Government (August 2024–Present)

Just two days after the ousting of Sheikh Hasina’s regime on August 5, 2024 by a mass uprising led by students, HTB held a protest in front of the country’s national parliament, known as Jatiya Shangshad (Bangla: জাতীয় সংসদ). Hundreds of HTB activists waved white flags engraved with the Islamic Shahada (Arabic: شهادة, lit. “bearing witness”; testimony of faith), distributed propaganda leaflets, and carried banners demanding the establishment of the caliphate. The group also occupied the area around the Raju Memorial Sculpture at Dhaka University, which symbolizes the fight against terrorism, on the same day (BBC News Bangla, September 13, 2024). [4] In the same month, HTB posters appeared at Gulshan Police Station, where a memorial stands for two Bangladesh Police officers killed in the infamous Holey Artisan Bakery attack by Islamic State in 2016 (Dhaka Tribune, August 29, 2024).

In September 2024, HTB started to pragmatically revamp its activities in Bangladesh just weeks after a more Islamist-friendly interim government, led by Nobel Laureate Professor Dr. Muhammad Yunus, took control of the country. Taking advantage of weak governance and the fractured law enforcement system, the group held a seminar at a Dhaka Reports Unity, a key journalistic facility, focusing on the Pilkhana Massacre (Prothom Alo Bangla, September 2, 2024). This was organized under an obscure organization named Bangladesh Policy Discourse (BPD). The seminar centered entirely on Indian dominance in Bangladesh and the need to establish a caliphate, eschewing any real discussion of the Pilkhana Massacre. Speakers included Md Jobayer, a faculty member at Dhaka University; Enayetullah Abbasi, a religious speaker; Helal Talukder, a former government official; and Mohammad Abdul Haque, a retired Bangladesh Army colonel (Prothom Alo Bangla, September 2, 2024). Although hosted under the banner of BPD, the BPD seminar the seminar featured on HTB’s official website, which further indicates the latter’s role in sponsoring it (Hizb ut-Tahrir Central Media Office, September 1, 2024).

Just a week after the seminar, in a separate press conference, HTB publicly called for the repeal of the ban on its activities and announced that it had petitioned the Home Ministry to that effect (Prothom Alo Bangla, September 9, 2024). HTB’s media coordinator and second-in-command, Imtiaz Selim, even gave an interview where he claimed that HTB members had actively taken part in the mass uprising in 2024 to remove Hasina from power. All these actions indicate a coordinated campaign by HTB to seek the reversal of their banned status and obtain legal sanction to operate (BBC News Bangla, September 13, 2024).

In October 2024, the interim government suddenly adopted a stricter stance against HTB, and Imtiaz Selim was arrested and remanded (Prothom Alo Bangla, October 4, 2024). In spite of this, HTB posters about establishing a caliphate and returning its legal status continued to appear (Benar News, October 8, 2024). The most significant event in post-uprising HTB activity occurred on March 7, with the “March for Khilafot” (Bangla: খেলাফত from Arabic: خلافة, “caliphate”). After Friday prayers, more than 3,000 HTB supporters gathered for a commemoration of 101 years since the end of the Ottoman Empire at the Baitul Mokkaram national mosque in Dhaka, chanting “Freedom has one path, Khilafot, Khilafot” (AP, March 7). Security forces were aware of the event at least a week in advance and even detained three coordinators during a night raid the day before the march. However, the police failed to control the initial gathering, and when HTB members began to march forward, security forces pushed back (The Business Standard [Bangladesh], March 6, 2024; DW Bangla, March 8). Dozens of people were injured, including journalists and police officers, and more than 30 HTB members were arrested, including the organization’s spokesman, Saiful Islam (DW Bangla, March 8). This sparked nationwide outrage—especially since the event was openly announced and the interim government failed to prevent violence.

Conclusion

Since the “March for Khilafot” scandal, the interim government of Bangladesh has begun taking measures to prevent internal and external security threats posed by HTB. In March, the security forces conducted raids and arrested two students of Cumilla University with links to HTB. In the same month, the police also arrested seven people from Dhaka’s elite suburb of Dhanmondi who sought to hold an “anti-genocide” rally for Gaza after Friday prayers that showcased HTB banners and placards (Prothom Alo Bangla, March 8). In July, the government also issued directives to the Madrasha (Bangla: মাদ্রাসা from Arabic: مدرسة, an Islamic educational institution) Education Directorate and Vocational and Technical Education Boards to curb HTB activities and enforce government-sanctioned religious narratives (Bangla Tribune, July 8; Kalbela, July 9). The government further prepared a list of cases against the organization related to militancy, extremism, and terrorism, and the CTTC head promised constant online surveillance of extremist groups to prevent future incidents (DW Bangla, July 2).

Despite these measures, threats remain. Previously, under the instructions of deposed prime minister Sheikh Hasina, security forces had brutally killed, abducted, and tortured many of her political rivals and dissidents—as well as innocent victims—alleging they were “militants or terrorists” to justify state-sponsored repression (BSS News, June 5). This incarceration of individuals after labeling them as violent extremists on falsified or extremely skewed charges is popularly known as jongi natok )Bangla: জঙ্গী নাটক, “militant drama”), which came to light after her regime collapsed (Prothom Alo Bangla, August 18). Ironically, the Hasina-era repression has now created an easy scapegoat for ideologues, activists, and Islamist online influencers to discard any existence of violent extremism in Bangladesh. By capitalizing on Hasina’s jongi natok crimes, they question the existence of violent extremism and, in turn, push a biased narrative that “all incidents of Islamist extremism and extremists in Bangladesh are fake.” While there is no doubt about staged “dramas” concocted for malicious political ends, it is also beyond doubt that violent extremism and terror are real threats, which have unfortunately been politicized by Islamists to gain popularity (New York Times, April 3).

This biased narrative has been reinforced by some top officials in the law enforcement community, including the Police Commissioner of Dhaka, who publicly denied the existence of terrorists in Bangladesh (DW Bangla, July 2). Although prominent security experts in Dhaka widely criticized him for these comments, the commissioner’s statement has only reinforced the politicization of alleged jongi natok incidents by the Bangladeshi Islamists (DW Bangla, July 2). Moreover, the country’s police have lost track of 712 trained HTB members and 174 convicted terrorists who fled after prison breaks during the July uprising (Desh Rupantor, March 11; DW Bangla, July 2). HTB, meanwhile, has expanded its membership to female cells, reaching high school and college students, and even top government officials as well as other exclusive elements of Bangladeshi society (Bangla Outlook, May 28). [5] All of these trends pose major internal security threats to Bangladesh (Desh Rupantor, March 11; S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Commentary, April 25).

Overall, the threats of HTB in Bangladesh and the surrounding region must not be underestimated. Two Bangladeshi police officials affirm that HTB is more deadly than other groups, as it recruits “intelligent and talented youths who receive special training” (Desh Rupantor, March 11). Bangladeshi officials must be proactive to counter the gray zone activities of HTB and develop a clear strategy to curb the group’s activities.

Notes:

[1] Then-Home Minister of Bangladesh Sahara Khatun stated, “The organization has been banned, as it has been carrying out anti-state, anti-government, anti-people, and anti-democratic activities for a long time in the country” (The Daily Star [Bangladesh], October 22, 2009).

[2] Mohiuddin Ahmed taught at Dhaka University’s Institute of Business Administration (IBA), Bangladesh’s most prestigious school for Bachelor in Business Administration and Master in Business Administration aspirants. Ahmed received bail from the High Court in May 2011. He was re-arrested in 2016 and was under trial for three years but was acquitted by the court in 2019, as the state failed to prove the case against him. However, his two accomplices were found guilty and convicted.

[3] The Pilkhana Massacre was a mutiny staged in late February 2009 in Dhaka by rebel soldiers of the Bangladesh Rifles (BDR), who comprised the former border security force of Bangladesh. The rebelling BDR soldiers took control of the BDR headquarters in Pilkhana and killed 57 army officers, including the then-BDR Chief.

[4] This is a famous national sculpture built in 1997 to commemorate Moin Hossain Raju, a central leader from the leftist student group Bangladesh Chhatra (Student) Union, and an activist against on-campus political violence. Protesting a shooting incident on the campus, he was gunned down in a crossfire between two rival groups on the university’s premises. The sculpture is set up to pay tribute to his memory and symbolize the fight against political violence, terrorism, and extremism.

[5] In an investigative report by renowned Bangladeshi journalist Zulkarnain Saer, Mohammad Azaz, the administrator (de facto Mayor) of Dhaka City-North, was allegedly involved with HTB, having been previously arrested and serving as a senior leader in HTB (Bangla Outlook, May 28). He was later acquitted of his charges after the interim government took power, and surprisingly was given the position of managing Dhaka-North, allegedly without security checks and recommendations, by two influential advisors within the Yunus administration (Bangla Outlook, May 28). Although Azaz issued statements denying all accusations, the allegations, as well as substantial evidence from police records, have been enough to tarnish the reputation of the interim government (Dhaka Tribune, May 18).