How U.S. Banks Push the Caribbean Toward China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 17

By:

Introduction

The 14th Five-Year Plan adopted this past March has reaffirmed the significance of Renminbi (RMB) internationalization in China’s geopolitical ambitions (Gov.cn, March 13). Global RMB proliferation in cross-border trade would enhance China’s domestic financial security, which also makes it a key element of China’s “dual circulation” (双循环, shuang xunhuang) strategy for economic development (East Money, August 22). As Huang Qifan (黄奇帆), the former Chongqing mayor and renowned authority on Chinese financial policy, has said, “[the] dual circulation strategy will provide a strong opportunity and impetus for the further development of the BRI” (Sina, September 12, 2020). China’s financial policy should be understood under the context of the party-state’s larger foreign policy ambitions. One region that would readily embrace China’s aim to incorporate a greater financial element to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the Caribbean.

The Caribbean countries are small and import nearly everything to meet the wants and needs of their populations. Since these imports are mostly priced in U.S. dollars (USD), the Caribbean’s economic security depends upon its financial relationships with a few large U.S. commercial banks. But following U.S. regulatory changes that took place after the 2008 financial crisis, some Caribbean countries have either lost access to or been restricted from previously existing channels to U.S. banks, putting them in a precarious position. In an effort to build economic resiliency, some Caribbean countries have begun seeking new avenues for international trade finance, including using the RMB, which potentially opens a door to growing Chinese influence in the U.S.’ backyard.

Background

Although the abstract concept of an “international wire transfer” is easy to grasp, the reality involves a messy process to coordinate different domestic transactions. Like all small states, Caribbean countries depend on Correspondent Banking Relationships (CBRs), wherein banks in small countries (respondents) hold accounts in banks of larger ones (correspondents) that enable them to access international financial markets.

Following the 2008 crisis, U.S. regulators increased the stringency of banking compliance requirements for the purposes of anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT). This culminated in sweeping reforms including the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010 and the 2013 U.S. Department of Justice Operation Choke Point effort to reduce the risk of money laundering in the U.S. banking system.

Such reforms (particularly the Dodd-Frank Act) increased the fines faced by U.S. banks for the (actual or perceived) risks and procedural failings of their respondent clients (Baker Institute for Public Policy, September 6, 2019). The intent was not to harm small banks in small countries, but, as with many complex financial system reforms, there were negative externalities. U.S. banks were required to design their own internal control policies to manage the risk of doing business with small international banks. Instead, the banks—understandably not willing to increase their costs for no extra profit—restricted or outright terminated their relationships with small banks. The finance industry refers to this process as “de-risking.”

The Specter of De-Risking

Global de-risking severely impacted the Caribbean in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis (World Bank, November 3, 2015). For example, Belize experienced terminations of Correspondent Banking Relationships (CBRs) that accounted for more than half of their banking assets (CFATF, March-April 2016, accessed August 12).

In 2016, the Honorable Francine Baron, then-Minister of Foreign Affairs of Dominica, focused her speech to the United Nations (UN) General Assembly on what she saw as the greatest developmental threats to Caribbean nations – climate change and de-risking; saying that “today’s interconnectedness of global markets make access to the global financial system a prerequisite to economic development and a sine qua non for sustainable development” (undocs.org, September 24, 2016). Baron’s concerns were echoed across the region. Speaking a year later, the Ambassador to the U.S. from Antigua and Barbuda Sir Ronald Sanders warned that “de-risking is a serious threat to Caribbean security” (The Tribune, March 27, 2017). All of the multilateral finance organizations that operate in the Caribbean also published scathing reports outlining the negative effects of continued de-risking (Caribbean Development Bank, 2016; Inter-American Development Bank, February 2017; International Chamber of Commerce, October 2019; accessed August 12).[1]

In a 2019 survey of Caribbean central bankers, 91 percent of respondents indicated that de-risking remains a threat to the operational viability of the banks in their respective jurisdictions.[2] De-risking is not merely an esoteric topic for closed-door financial policy discussions. Since 2010 this has been one of the main animating concerns underlying current Caribbean foreign policy towards the U.S., and it continues unabated.[3] Accordingly, Caribbean governments and central banks have begun planning contingencies including the increasing adoption of the Chinese RMB.

Toward the RMB in the Caribbean

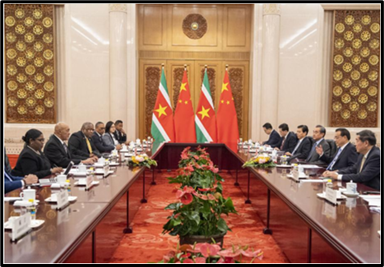

In 2015, the Central Bank of Suriname signed a Bilateral Swap Agreement (BSA), also known as a cross-currency swap agreement, for 1 billion RMB ($154.34 million) with China (Centrale Bank van Suriname, January 28, 2015). Such agreements give the recipient party (in this case, Suriname) the right to exchange currency with China at a fixed interest rate, reducing the risk of currency conversion fluctuations and lubricating cross-border trade. China has signed 35 BSAs globally, compared to the U.S.’s 14, and has historically used BSAs as a tool for internationalizing the RMB (The China Guys, July 6, 2020).[4] Suriname is currently the only Caribbean country whose currency is tradable directly with the RMB. Reflecting this unique relationship, a Chinese bank called Southern Commercial Bank (南方商业银行, nanfang shangye yinhang) issues UnionPay cards in Suriname (Southcommbanknv.com, accessed August 12).

Following the example of Suriname, other Caribbean countries could actively seek to attract more Chinese banks to fill the void left from the exodus of their traditional partners. Many U.S. banks have departed the Caribbean as profits dwindled, and the largest banks remaining in the Caribbean are currently Canadian. Many of these are now departing as well due to the rising costs of continuing to operate in the Caribbean. Just this year, the Royal Bank of Canada sold its operations in seven Caribbean countries (Newswire, April 1).

In contrast to the decline of Caribbean-U.S. CBRs, the number of Chinese CBRs increased globally from 65 in 2009 to 2,246 in 2016—representing growth of more than 3,355 percent (Accuity, accessed August 12). The rapid increase is a strong indicator that the trend will continue. Additionally, if the Caribbean can pay for Chinese imports using the international Cross-border International Payments System (CIPS, 跨境银行间支付清算, kua jing yinhang jian zhifu qingsuan) (CIPS, accessed August 3), this will lessen the region’s reliance on USD for trade. It also follows that if the Caribbean can use the RMB for imports, then it lessens the dependence on U.S. CBRs, improving the region’s economic resiliency.

The U.S. remains the Caribbean’s largest trading partner according to trade volume. This point is frequently made to demonstrate the strength of regional ties (e.g., The Hill, December 1, 2020). But the size of U.S.-Caribbean trade is the result of measurement constraints, not necessarily economic reality. As with much of the rest of the world, most products sold in the Caribbean are made in China and re-exported through the U.S. If the strength of bilateral trade is calculated based on the manufacturing origin of the goods consumed, then China could be considered the Caribbean’s largest trading partner.[5] The high volume of the U.S.-Caribbean trade is effectively phantom trade. There exists a possible future where goods are shipped directly from China to the Caribbean, circumventing the U.S.’ traditional position as a middleman.

Other factors could also lead Caribbean states to increase their trade purchases from China using the RMB. Traditional shipping routes have privileged trade from the U.S. to the Caribbean. But this is changing because of increased Chinese port construction across the Caribbean (Tearline.mil, August 14, 2020). Caribbean businesses in the past have not had easy RMB access and they have not established direct relationships with Chinese suppliers. But if more Caribbean central banks hold RMB reserves (following the example of Suriname) and more businesses develop relationships with Chinese suppliers (as they have been increasingly doing), their ability to bypass the U.S. dollar market grows.

RMB Internationalization

Wide-scale RMB usage in the Caribbean does not currently exist, and skeptics might argue that the RMB is not sufficiently internationalized to be able to replace the dollar’s comprehensive regional dominance. The Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) published a report in 2017 titled Chinese Renminbi in the Caribbean: Opportunities for Trade, Aid and Investment (CDB, accessed August 12). Most of the discussion centered on the prospects of RMB internationalization and how the Caribbean could potentially tap into this growing benefit in the future.

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) cross-border currency transaction data shows that the share of RMB is currently tiny (1.30 percent) compared to USD dominance in international payments (87.06 percent). The volume of global payments done via RMB is similarly small (2.20 percent) compared to USD (38.43 percent) (SWIFT, accessed August 24). RMB internationalization has not progressed much on a global scale. But Caribbean economies are themselves also small. If all of the Caribbean economies were to conduct all of their international trade payments in RMB, it would merely move the current RMB share of cross-border currency transactions by a few basis points. What matters for Caribbean economies is not aggregates of trade finance or payments throughput but instead sufficient access to RMB exchange, clearing and settlement facilities, which has seen material growth.

The Chinese government has recently signaled that it is willing to assist countries in developing such facilities. In January 2021, the China-Mauritius Free Trade Agreement (FTA) came into effect (The Mauritius Chamber of Commerce and Industry, October 17, 2019). Section 12.8(e) of this FTA stated that China will be “promoting the development of a Renminbi clearing and settlement facility in the territory of Mauritius” by sharing technical expertise and providing financial assistance. China’s willingness to assist in similar future endeavors with Caribbean countries should be considered in the context that Chinese banks tend to have higher risk absorption characteristics and would be more tolerant of the higher structural risk in the Caribbean.

Some have argued that large Chinese banks have less mature risk management capacity than their US counterparts, primarily because the rapid growth, marketization and internationalization of Chinese banks has outpaced their ability minimize risk management constraints.[6] But in this case it is necessary to remember that large Chinese banks are state-owned enterprises whose risk capacity has to be contextualized within the broader policy ambitions of the Chinese state. The Chinese economist Cheng Cheng (程诚) has argued that Chinese banks tend to practice “stem cell finance” (造血金融, zao xue jingrong) in emerging markets in Africa, making an analogy that—similar to the process of growing new blood cells—international development financing is unavoidably energy intensive and slow but unequivocally essential.[7] According to Cheng’s argument, Chinese banks acknowledge that financial profits can only be achieved after risks are absorbed in the long term.

This July, the central Chinese government announced the “Opinions Advancing a High Level of Reform and Opening Up of the Pudong New Area to Build a Leading Area of Socialist Modernization” [关于支持浦东新区高水平改革开放打造社会主义现代化建设引领区的意见], Guanyu zhichi Pudong Xinqu gao shuiping gaige kaifang dazao shehui zhuyi xiandaihua jianshe yin lingqu de yijian), a monumental plan to transform Shanghai into the core financial center of the world (Gov.cn, July 15). In addition to providing a framework for innovation and urban development goals, the plan calls for further liberalizing China’s capital account to enable RMB to trade more effectively on international markets. It envisions a whole-of-government approach to “deeply integrate [China] into global economic development and governance” (Gov.cn, July 15); this is the policy context that Chinese banks are working under. Under such state-driven imperatives, Chinese banks—in contrast to their U.S. counterparts—will strive to widen the correspondent reach of their national currency.[8]

Conclusion

AML and CFT compliance regulations are not typical geopolitical topics unless international sanctions are being discussed. For this reason, one of the most significant economic security threats facing the Caribbean has largely been ignored by U.S. foreign policy analysts. As the regulatory environment of U.S. financial markets continues to corrode the economic security of Caribbean countries, it is inevitable that they will seek to maintain resilience. With no other options available to them, this will likely mean the increased usage of the RMB. Such a development would be significant for several reasons. First, states have been haunted by the prospect of the U.S. weaponizing the dollar for geopolitical ends, but little concern has been placed on the lethal consequences of seemingly benign regulations aimed at addressing money laundering and counter-terrorism issues. The current Caribbean predicament brings this reality to light.

Second, the Caribbean has been colloquially referred to as “America’s backyard” by U.S. policymakers for decades, but the U.S. ineffectual response to its close allies’ worries is concerning and bodes ill for efforts to counter the growing economic security threat from China in further regions. Third, if the RMB takes a foothold in the Caribbean, it will act as a case study of countries in the Western Hemisphere becoming closer to China not because of China’s pull, but rather because they are pushed away by the U.S.

Rasheed Griffith is a Senior Fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue and Host of the ‘China in the Americas’ Podcast. His research focuses on China’s financial and geoeconomic engagement in the Americas.

Notes

[1] For examples, see: “Discussion Paper: Strategic Solutions to ‘De-Risking’ and the Decline of Correspondent Banking Relationships in the Caribbean,” Caribbean Development Bank, 2016, https://www.caribank.org/publications-and-resources/resource-library/discussion-papers/discussion-paper-strategic-solution-de-risking; Allan Wright and Bradley Kellman, “De-Risking in the Barbados Context,” Inter-American Development Bank, February 2017, https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/De-Risking-in-the-Barbados-Context.pdf; De-risking: the hidden issue hindering SDG progress and threatening survival of small island states, October 2019, https://iccwbo.org/media-wall/news-speeches/de-risking-the-hidden-issue-hindering-sdg-progress-and-threatening-survival-of-small-island-states/.

[2] See: ”De-Risking in the Caribbean Region: A Caribbean Financial Action Task Force Perspective,” CFATF, January 30, 2020, https://www.cfatf-gafic.org/documents/resources.

[3] After years of vigorously lobbying the U.S., Caribbean countries have achieved only moderate success in turning back the tide of de-risking. It will take years for the tentative support for anti-de-risking in legislation such as the William M. Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 to be presented, debated and implemented. See specifically Section 6215 (b)(2)(c) and Section 6215(c)(4) in the NDAA 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6395/text.

[4] As of January 2020, a full list of China’s currency swap partners includes: Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia, Argentina, South Korea, Belarus, Iceland, Singapore, New Zealand, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Thailan, Pakistan, UAE, Turkey, Australia, Ukraine, Brazil, UK, Hungary, Albania, Eurozone, Switzerland, Sri Lanka, Russia, Qatar, Canada, Suriname, Armenia, South Africa, Chile, Tajikistan, Georgia, Morocco, Serbia, Egypt, Nigeria, Japan, Macao, Laos (Hindu Business Line, December 2020).

[5] See: DeLisle Worrell, “China in the Caribbean’s Economic Future,” August 6, 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3668058.

[6] See: Hu Jiarui (胡佳睿), “Analysis on the Credit Risk Management and Control of [Chinese] Commercial Banks” [浅析我国商业银行信贷风险管理与控制], Taxation [纳税] 08 (2018), https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx; Deng Ye (邓野), “Discussion on Commercial Bank Credit Risk Management” [谈商业银行信贷风险管理], Shenyang Chemical Engineering University Economics and Management School, https://www.xchen.com.cn/tzlw/grxdlw/740646.html.

[7] Cheng Cheng (程诚), “The ‘One Belt One Road’ China-Africa New Development Cooperation Model: How ‘Stem Cell Finance’ Can Fix Africa” [‘一带一路’中非发展合作新模式: ’造血金融’ 如何改变非洲], Renmin University, September 29, 2018, https://www.cssn.cn/jjx_lljjx_1/lljjx_blqs/201809/t20180929_4663266.html.

[8] Specifically, the plan calls to “Support Pudong to take the lead in exploring the implementation path of capital account convertibility” (支持浦东率先探索资本项目可兑换的实施路径) (Section 5, Subsection 13), and “Innovate international-facing RMB financial products, expand the scope of overseas RMB [and] domestic financial investment products, promote the two-way flow of cross-border RMB funds” (创新面向国际的人民币金融产品,扩大境外人民币境内投资金融产品范围,促进人民币资金跨境双向流动) (Section 5, Section 13), https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-07/15/content_5625279.htm.