Identity Crisis in the Making of Sahel Militants

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 23 Issue: 8

By:

Executive Summary:

- Militant groups in the Sahel exploit widespread youth isolation and social breakdown—offering young men belonging, purpose, and brotherhood that mimic and replace weakened family and community ties.

- Radicalization often follows a predictable psychological path: limited personal agency and strict social conformity in childhood give way to confusion, alienation, and eventual dependence on militant “families.”

- Traditional Sahelian values of obedience and honor, once stabilizing, are repurposed by jihadist recruiters as moral justification for violence when clan or state authority collapses.

- Sustainable counter-radicalization must focus on rebuilding genuine community bonds and youth inclusion, using local clerics, elders, and mentors to replace the false intimacy that militant groups provide.

Youth participation in insurgency in the Sahel cannot be explained by poverty, politics, or ideology alone. High rates of radicalization in remote regions of Mali, Niger, and elsewhere in the region emerge from a serious psychosocial crisis affecting young men growing up amid family disruption, displacement, and collapsing social institutions. In this environment, militant groups exploit emotional and identity voids—offering recruits a sense of belonging, purpose, and fraternity that replaces absent social structures. This dynamic of isolation and “pseudo-intimacy”—where militant brotherhoods mimic genuine community—helps explain why extremist movements continue to regenerate despite years of counterterrorism operations.

Pastoralist Dislocation and Urban Despondency

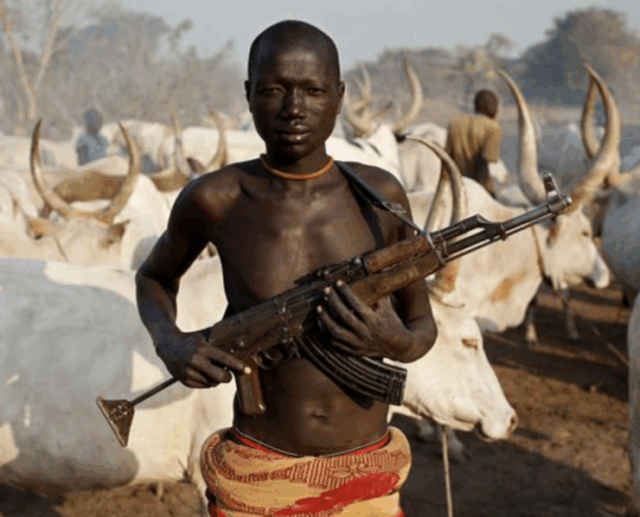

Many of the major ethnic groups in the Sahel find themselves at the crossroads of severe social and political crises. Pastoral groups like the Fulani and Tuareg traditionally rely on semi-nomadic forms of animal husbandry; the Tuareg mostly herd camels, goats, and sheep, while the Fulani are known for cattle herding. [1] Pastoral livelihoods depend on seasonal cycles that govern the movement of livestock. When these cycles are predictable, they allow for set paths and regular migration schedules and the ability to negotiate for safe passage and trade with sedentary communities along the way. Increasing desertification and more severe dry seasons in the Sahel force pastoralists to take unusual routes and contend with sedentary communities over limited grazing land and water, which frequently turn deadly (Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, February 8, 2019). What was once a reasonably predictable cyclical migration has become a life of flight, livestock theft, and killing vis-à-vis sedentary and other pastoral groups, fragmenting existing social structures. These peoples also have complicated relationships with local states, who view them largely outside of their purview, since their transnational migration patterns defy territorial control. Neglect contributes to even greater alienation and lack of access to services that abate poverty and promote maladaptation to social collapse. Pastoralism is also the heart of Tuareg and Fulani culture, without which they would endure loss and degradation. Many pastoralists end up in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, without their livestock, forcing them into banditry and criminal activity to survive (OECD, July 2021).

Urbanites in the Sahel suffer from similar societal dislocation in a different setting. While not as prone to militancy as their pastoral counterparts, endemic poverty, unemployment, lack of state services, overcrowding, and displacement in city slums from rural regions (some of whom are dislocated pastoralists) feed a similar form of individual isolation and social breakdown.

Local jihadist groups exploit these trends for recruitment. The Macina Liberation Front (MLF) and Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (Arabic: جماعة نصرة الإسلام والمسلمين, JNIM) take advantage of many Fulanis’ situation: geographic displacement, loss of cattle, and restrictions on the nomads’ grazing (Defense Web, November 13, 2017). Many Fulani villages are now deserted, as the conflict in Mali has displaced around 200,000 due to conflict, most of them in the country’s central Mopti region (Pulse Live Kenya, August 20, 2024). It is clear that Fulani youth sometimes join jihadist or other armed groups after their herds are taken, seeking self-defense or revenge before any ideological or religious conviction (Afrik Infos, July 31, 2025).

In Mali, jihadist groups are gaining more power over urban youth, who are unemployed and marginalized due to social and economic dysfunction. JNIM follows a similar strategy, exploiting regional instability, poverty, and weakened state structures in the Sahel (The Guardian, June 25, 2025). The phenomenon of urbanized recruitment appears implicitly in discussions of how youth in the Sahelian cities respond to failed state services, low employment, and social fragmentation (Defense Web, March 22, 2022).

Psychological Framework

The crisis affecting dislocated men in the Sahel can be understood in terms of modern psychology. German–American psychologist Erik Erikson (1908–1994) posited that an individual’s life comprises eight stages of development, each with a fundamental internal conflict to resolve. In this schema, the sixth stage of life, Young Adulthood (ages 19–40), is determined by the ability and desire to form close, mutual relationships. If a person proves successful, they become socially resilient and well-adjusted. If not, they carry forward relational deficits, including vulnerability to manipulation and an increased likelihood of continued isolation (Erikson, 1950).

James Marcia (1937–) developed Erikson’s model into four identity types. In Marcia’s framework, “exploration” refers to an individual’s search for identity through questioning one’s beliefs and goals, whether by choice (self-exploration) or as the result of a crisis that disrupts existing identity. “Commitment” indicates settling on a definite set of beliefs, values, or goals as part of an identity. The following are the possible Marcian methods of forming identity within a given Eriksonian stage of development:

- Diffusion: No exploration or commitment, with no significant impact on identity.

- Foreclosure: Premature commitment with no exploration. This involves settling on a predetermined identity or value system with little personal investment in the choice, often because of external pressure.

- Moratorium: Exploration without commitment. Moratorium is a state of experimentation (voluntary or not) or significant flux in identity, values, and goals, but with little to no commitment to a new way of life.

- Achievement: The settling of identity in line with exploration, essentially positive identity evolution (Marcia, 1993).

The path from childhood to militant recruitment can be understood through the following progression of psychological states:

Foreclosure → Moratorium → Isolation → Pseudo‑Intimacy

- Foreclosure through Socialization

In remote areas of northern Mali and western Niger, young men’s upbringing is significantly influenced by Islamic law, tribal honor codes, and hierarchies of communal obedience. Each of these elements reinforces the acceptance of collective opinion and discourages personal reasoning (Mali Actu, August 21, 2015). As such, foreclosure is a dominant result of stages throughout childhood, imposed through conservative schooling, family pressure, and strict community norms that restrict personal exploration or self-actualization.

Many Sahelian societies are marked by strict honor codes. Within the societies of the Tuareg, Fulani, and Songhai, the concept of asabiyya (from Arabic: عصبية), a group solidarity based on kinship, lineage, and allegiance, is vital to an individual’s identification. Men are socialized to protect collective honor (amana or laamu), obeying elders, and not expressing dissent. Among the Tuareg people, the code of asshak (honor and restraint) requires humility, discretion, and unswerving loyalty to clan hierarchies. The pastoralist Fulani people place themselves under the ethic of pulaaku, which prescribes self-control, respect for authority, endurance, and conformity. Despite differing in approaches, all these communities manage to maintain social order through their respective systems, which also promote foreclosure by limiting free thought.

Education also plays an important role in leading students to foreclosure. In northern Mali, this education system, heavily influenced by Maliki (Arabic: المالكي) law, easily brings about this mindset in its students, where a strong moral order is accompanied by limited self-exploration or critical thinking. In several parts of the Sahel, rural men are educated largely through madrasas and Quranic schooling, where the assimilation of the teacher’s (Arabic: مرابط, marabout—a traditional Islamic educator common in North and West Africa) will is considered the basis of moral education (Karamogo Mali, March 18, 2013). Islamic emphasis on scholarly discourse and reasoning (Arabic: اجتهاد), present in some Islamic societies, is nearly absent here, giving way to rote recitation and memorization. This approach breeds a culture of submission, respect for authority, and dependence on existing social structures.

Young men are subject to cognitive dissonance when marabouts and tribal leaders lose their credibility, and other authorities, like state elites, have failed, but their worldview craves direction before being able to question the need to submit to authority. In the absence of old, societally legitimate authority figures, they seek new sources of guidance.

- Moratorium and Radical Re-Socialization

In the moratorium phase, individuals undergo exploration—often through crisis—without being committed to an identity. Identity confusion and moratorium arise amid dislocation and trauma—resulting in a prolonged sense of uncertainty that militant networks exploit (Le Sahel, January 28, 2025). Without experiencing the process of healthy trial and error that is fundamental to development at this age, the adventure of jihadism or militancy looks far more attractive (International Alert, July 2020).

Extremists capitalize on this interstice by presenting jihad as a campaign to restore morality. Not only do they often claim to restore divine backing and the community’s honor, and to reinstate their position as the rightful heirs to tradition. This is an infectious message for a class of young men dependent on traditional leadership yet deprived of it.

Honor codes that previously functioned as social stabilizers can be twisted into tools of radicalization. The same deeply rooted obedience among the Tuareg, the code of asshak, is easily channeled toward militant ideologies when displacement, marginalization, and the erosion of clan or state protection weaken these traditional frameworks. Without a traditional leadership class to defer to, jihadist leaders easily recruit young men, presenting themselves as authority figures, moral protectors, and avengers of community dignity (Studio Amani, June 5, 2024).

When the situation of foreclosed identities coincides with the breakdown of institutions, young men’s loyalty, based on principles like asshak and pulaaku, inevitably finds a new authority to depend on. Militant recruiters make use of this situation by utilizing the present-day moral vocabulary of Islamic virtue, honor, and brotherhood, while re-socializing the recruits into new pseudo-families similar to traditional hierarchies. In this way, jihad no longer appears as a revolt—rather, it is considered a means of regaining power and respect during a period of prevailing disorder and corruption. Many youngsters in Douentza and Gao in Mali do not view militancy only as fighting for God’s cause, but as a form of “moral repair:” an individual and collective response to systemic injustice and the breakdown of trustworthy authority (Cultures of West Africa, October 9).

- Isolation: Withdrawal and Social Disconnection

If withdrawal lasts long enough, isolation gradually sets in. Social fragmentation in the Sahel has intensified over years of violence, migration, and loss of trust in both community and state. Individuals in IDP camps are often cut off from their sense of communal belonging, personal recognition, and purpose, a situation that feeds recruitment and a self-perpetuating cycle of breakdown and dependency. At this stage, recruits are invested in militant groups that now give them greater belonging than family and existing social networks.

Isolation can take various forms:

- Family: Orphans, young men cut off from care with no father-figures, or families torn apart by conflict or migration.

- Community: Minority ethnic groups, such as Fulani or Tuareg, are treated as outsiders. Their youth are ostracized by sedentary farming communities and have difficulty accessing state services. For example, the marginalization of Fulani pastoralists in Ghana has been highlighted as a driver of ethnic grievance (Foreign Policy, May 14, 2024).

- Economic: Unemployment or lack of vocational opportunities, particularly in the remote Sahelian regions where pastoralist livelihoods are collapsing due to drought. This is further compounded by land-access issues and poor governance (Euraafrica, March 25, 2023).

Militant organizations fill these voids by providing a sense of ambition, company, and close relationships, showing that recruitment is just as much about a false promise of self‑actualization as it is about any ideology.

- Pseudo‑Intimacy: Surrogate Brotherhood

The last stage of radicalization and social breakdown is pseudo‑intimacy, a condition in which emotional dependency on the militant group takes the place of a healthy community. In this stage, the new inductees go through a process of false kinship in the forms of vows, common routines, and shared hardships. This imitation of brotherhood prompts cutting family ties. Importantly, militant pseudo‑intimacy is conditional: love and support depend on following rules and adhering to ideology, while loyalty to the cause is the basis of trust.

The militant factions develop surrogate forms of intimacy that approximate real social relationships. Trust and loyalty are pretended through the practice of oath-taking rituals. Living together in camps, the militant analogy to a family, is composed of sharing habits, collective reliance for survival, and daily interdependence. The group’s belief system takes over the traditional ways of social recognition, reassigning value in terms of obedience and ideological conformity (International Alert, July 2020).

These manufactured relationships serve not only to reinforce loyalty and accelerate operational efficiency but further isolate the recruits from partaking in healthy existing communities, such as the natural decentralized networks characteristic of many pastoralist groups in the region. The youth–group interaction proceeds such that the youth’s emotional dependency strengthens the group’s control, while isolation from civilian life exists as both a result and a tool of prolonged radicalization—creating a vicious cycle of isolation and further investment in violence.

Illustrative Examples

The following vignettes are composite illustrations based on documented recruitment and identity patterns in the Sahel rather than direct case studies. While the characters are fictitious, they illustrate the psychological and environmental drivers for radicalization in the Sahel. [2]

Displaced Pastoralist: Aminu, rural Mali

Aminu is a young Fulani pastoralist whose formal education in a local madrasa left him with limited options to develop, causing him to reach foreclosure. Once he had already foreclosed, displacement due to cattle theft by local insurgents triggered a moratorium phase. In moratorium, Aminu looked for a familiar structure and authority to replace the existing structure he lost in displacement. He failed to find it, due to the breakdown of his family and community in their new location, leading him to the isolation stage. Islamic State–Greater Sahara (ISGS), then operating in this area of his displacement, and promising vigilantism against Tuareg who had assailed his family, offered him surrogate brotherhood, allowing him to attain pseudo‑intimacy with his fellow militants in exchange for operational loyalty and exploitation of his local mobility and networks.

Urban Youth: Ibrahim, Bamako

Ibrahim, a boy in Bamako (the capital of Mali), was cut off from family and community. Living in poverty, he is easily attracted by the militant networks’ offers of identity and purpose. While Ibrahim is not subject to the same Fulani honor codes and social pressures as Aminu, urban poverty, overcrowding, and lack of services, combined with a tight-knit and conservative-religious environment under tension produce many of the same harmful conditions that foster condition foreclosure (lack of personal exploration, acceptance of authority, reliance on social structures) into moratorium, in which breakdown of these structures triggers affected individuals to seek out new and similarly moralistic, conservative, and intimate structures, like jihadist groups. Ibrahim goes on to fight for al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) but is later captured and deradicalized.

Conclusion

Youth in the Sahel are attempting to survive in an environment marked by instability and lacking opportunity. It is vital for decision-makers, humanitarian organizations, and military planners to understand the reasons that lead youth to join extremist networks. Critical among these factors is social isolation and societal breakdown, which militant groups take advantage of by portraying their own groups as “pseudo-intimate.”

In both rural and urban settings, distinct psychosocial patterns can be seen clearly. Disrupted identity formation, caused by enforced conformity or social abandonment, opens the emotional space for militant groups to move in. The same human ties, if rightly understood, can be transformed from vectors of recruitment to tools for stabilization.

The health of youth networks can be a strong indicators of the risk of radicalization. Programs that incorporate local dialogue platforms, livelihood restoration, and peer-mentorship models have proven to be more resilient than purely kinetic or externally driven security interventions.

From a tactical viewpoint, the decentralized local networks prevalent amongst the Fulani and Tuareg should provide the military with superior intelligence and longer operational reach. These pastoralist and nomadic communities typically traverse areas with little state presence, possess knowledge of local terrain, move together as family units, and establish channels for informal communication among their different sub-groups. Insurgent groups can infiltrate as they assimilate into these networks: recruiting cattle herders who regularly cross borders, using existing clan ties to gather intelligence and provide supplies, and locating safe havens. Since these social networks are based on local socio-ecological movements rather than fixed installations, state forces unfamiliar with the local rhythms find it very hard to gain access to these social networks or interact with them in a meaningful way. Decentralized pastoralist structures become a double-edged sword: an excellent intelligence asset if engaged correctly, but currently a major advantage for militant groups when misunderstood and left unattended.

Under the paradigm of militant pseudo-intimacy, communities’ health must be understood as a part of the solution, especially to prevent early moratorium that leads young men to fall into the arms of terrorist organizations. The empowerment of credible local actors, teachers, clerics, ex-combatants, and women mediators can turn social cohesion from a liability into an asset for security (Punch, November 6). The same social structure that supports interpersonal relationships in militant camps can, if properly directed, be the source of genuine belonging and resistance to violent extremism.

[1] Fulani also herd goats and sheep, but at a comparatively lower rate.

[2] The “Aminu” and “Ibrahim” profiles are composite examples constructed from publicly available reports and research on youth radicalization in the Sahel.