Is there a Revival of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan?

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 39

By:

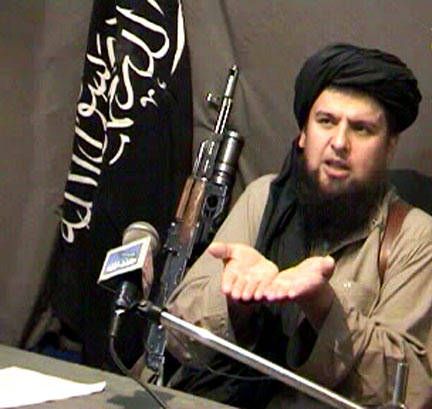

The death of Tahir Yuldash, the late leader of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), in an August 2009 U.S. Predator airstrike in Pakistan raised questions surrounding his succession and the continued viability of the IMU as a terrorist organization. Yet a year after the killing, and following many more years of targeted attacks by Coalition forces in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the IMU not only has a new leader, Abu Uthman Adil, but is also supposedly becoming more active in Tajikistan and the northern areas of Afghanistan (for Adil, see Furqon.com, August 17). Assessing the capabilities and future of the IMU is thus highly pertinent in light of intensified drone attacks against the group’s forces, the planned U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan and ongoing talks with the Taliban.

The IMU originally had a strong presence in the impoverished Fergana valley of Central Asia, where it had unsuccessfully attempted to establish a caliphate by replacing the secular regimes of the post-Soviet Central Asian countries. In practice, most of its efforts centered on Uzbekistan. Faced with resistance after some initial success, the group was forced to retreat to Afghanistan, where the Taliban regime provided it with a sanctuary in the late 1990’s. As a result of the military response by the United States and its NATO allies following the 9/11 attacks, the IMU suffered heavy losses, with most of its members following the Taliban to the Afghanistan-Pakistan frontier to regroup and raise funds. Over the years, the IMU has worked closely with al-Qaeda and the Taliban, training jihadists in Pakistan and Afghanistan and capitalizing on the regional drug trade.

According to General Abdullo Nazarov of the Tajikistan State Committee for National Security, the IMU consisted of three factions in 2009 (Deutsche Welle, April 25, 2009). This may well indicate flexibility and adaptability rather than disunity in the organization. The IMU is known to have produced an offshoot called the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU), which operates in Europe and espouses a much more global jihadist agenda (see Terrorist Monitor, November 8, 2007; April 9, 2010). It also has its own allies, including al-Qaeda, the Taliban and the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM). Operational and financial constraints have apparently led the IMU to seek the support of other jihadist organizations in advancing global jihad. The IMU, for instance, trained militants who recently planned al-Qaeda-coordinated attacks against European cities (Nezavisimaia Gazeta. October 15).

Currently, the IMU’s strength is unknown, but recently forces have been targeted by intensified drone attacks in both Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, which may be forcing them to flee and step up their activities in Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan (tjknews.com, October 4). The group may also be seeking to undermine the Northern Distribution Network that runs NATO supplies across Central Asia to Coalition forces in Afghanistan.

In September 2010, the IMU issued a statement claiming that inmates who escaped from a prison in Tajikistan in August 2010 were passed to a safe place. According to Muhammad Omar, the late governor of Afghanistan’s Kunduz province, most of the escapees took cover in the Taliban-controlled areas of northern Afghanistan (Newsweek, October 3). On September 3, a suicide bomber set off an explosion at a regional police unit in Khudzhand. Officials initially blamed the IMU for the attack, which was later claimed by a previously unknown group calling itself Jamaat Ansarullah. A regional prosecutor claimed on October 14 that the new movement was part of the IMU, but a week later Interior Minister Abdurahim Kakhorov disregarded the claim, saying a full investigation into the group was required (Kavkaz-Tsentr, September 8; Rian.ru, October 14; IWPR, October 21).

The IMU also claimed responsibility for the September 10 ambush of a military convoy in the Kamarob gorge that killed 28 soldiers, though the government accused Tajik militant Abdullo Rakhimov (a.k.a. Mullo Abdullo) of carrying out the attack (ferghana.ru, September 24; centrasia.ru, October 14; tjknews.com, October 4; see also Terrorism Monitor, October 4). The attacks were allegedly in response to Tajikistan’s support of Coalition forces, restrictions on Muslim practices and arrests of a number of Muslim activists.

Critics of the Tajik regime believe that the authorities inflate the IMU threat in order to secure Western support and assistance (www.ferghana.ru, October 4). However, if claims about recent IMU attacks in Tajikistan are true, northern Afghanistan and Central Asia may encounter a more potent IMU threat as Coalition forces scale down their military presence in Afghanistan. For now, the available data suggests that the IMU has survived the death of its longtime leader, even if IMU forces may be running from the intensified attacks of Coalition forces. Compromises with the Taliban could allow the IMU to regroup and intensify its operations in Central Asia.

How the military campaign ends in Afghanistan will thus affect the IMU’s future. Talks with the Taliban will not only determine the post-war position of the Taliban but also that of the Taliban’s ally – the IMU. The role of the Pakistani military will also be critical for the IMU’s future operations. Currently, Pakistani tribal leaders host IMU fighters, while the Pakistani military is unwilling or unable to clamp down effectively on the Taliban and its affiliates in the country’s tribal areas. Pakistan fears that doing so would deprive it of an opportunity to use the Taliban as an asset in a confrontation with India.

The extent to which Central Asian states, their partners and regional security bodies are capable of thwarting potential IMU infiltrations will determine the IMU’s future trajectory. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are particularly weak in this regard. The two countries already experienced IMU incursions in 1998. Both states are also experiencing high levels of political instability, with Tajikistan enduring frequent terrorist attacks and Kyrgyzstan becoming vulnerable to external threats in the aftermath of the April 7 government overthrow and clashes between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in the Fergana valley. The support of Russia, the United States and China, as well as the Collective Treaty Security Organization (CSTO) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), will therefore be crucial in bolstering regional defenses against a reinvigorated IMU threat. Cultivation of the region’s traditionally tolerant Islam and advancement of socio-economic and political conditions will further contain the influence and operations of radical and terrorist movements such as the IMU.