Jihadists and Saudi Arabia in the Shadow of the Arab Spring

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 45

By:

In the 1980s the Saudi Arabia-United States alliance supported the mujahedeen in Afghanistan in their battle against the Soviet Union. Hostility has since grown between al-Qaeda, which formed later and the Saudi regime. Hostilities started after the 1991 Gulf War when the Islamic opposition became incensed at the decision to invite non-Muslim troops (i.e. the Americans and their Western allies) to use Saudi soil to attack invading Iraqi forces in neighbouring Kuwait. By then the jihadists had theorized on the “infidelity” of the Saudi state; an ideology Jordanian Islamist Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi described in one of his most famous works, Al-kawashif al-jaliyya fi kufr al-dawla al-Sa`udiyya (The Shameful Actions Manifest in the Saudi State’s Disbelief).

If al-Maqdisi laid the foundation for the enmity between jihadists and Saudi Arabia, Osama Bin Laden took it to the next level in the mid-1990s when he turned from criticizing the Saudi state to considering it explicitly a kafir (non-believing) state against which Muslims were obliged to wage a jihad. In this stage several small bomb attacks were committed in the capital of Riyadh. The most significant of these was the November 1995 car bombing that killed five U.S. citizens and two Indian citizens at the offices of the Saudi National Guard on Riyadh’s al-Olaya road.

After 2000 the violence escalated between both parties until it reached a peak in 2003, when Saudi jihadists returning from Afghanistan launched a jihadi campaign that lasted until 2007. Saudi authorities dismantled the structure of the Saudi jihadist movement in that year, leading them to migrate to Yemen, where they merged with Yemeni jihadists to form al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The newly formed movement quickly became a national threat to Saudi Arabia.

The Challenge of the Arab Spring

The “Arab Spring,” the disparate youth-led revolutions that toppled a number of long-lasting Arab despots, presented a challenge for both Saudi Arabia and the jihadists. The Saudis are concerned with their troubled neighbours of Bahrain and Yemen as well as the potential growth of political movements inside their own country. The jihadists, meanwhile, have lost much of their usual recruitment pool as the Arab youth movements provide an alternative to their violent ideology.

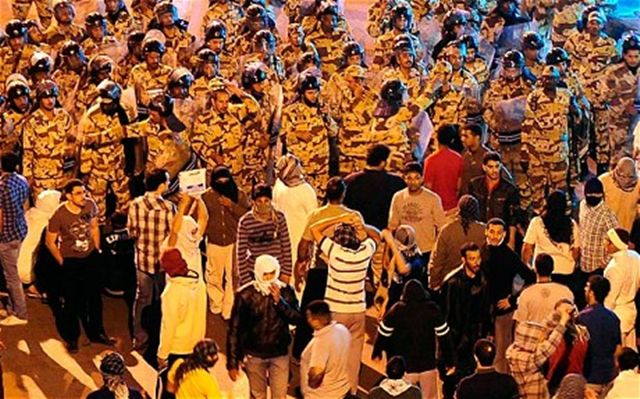

The Saudis have taken several steps to prevent any troubles within or along its borders, including the deployment of troops of the Gulf Cooperation Council’s (GCC) Peninsula Shield Force (PSF) to Bahrain and supporting the GCC initiative for a transition of power in Yemen (for the PSF, see Terrorism Monitor Brief, March 24). Locally, Saudi authorities have resorted to a stick-and-carrot policy. In February King Abdullah, according to an official statement read on Saudi state TV, “boosted spending on housing by 40 billion riyals ($10.7 billion)… earmarked more funds for education… raised the social security budget by 1 billion riyals…and ordered the creation of 1,200 jobs in supervision programs and made permanent a 15% cost-of-living allowance for government employees” (Saudi TV 1, February 23; Bloomberg, February 23).

On other hand the Saudi government cracked down on any opposition voices in the country. Amnesty International recently released a report claiming that hundreds of people in Saudi Arabia “had been arrested, many of them without charge or trial.” Prominent reformers had been given long sentences ranging from five to thirty years in prison following trials which Amnesty called "grossly unfair." [1] These trials increase anger among Saudi youth on social media outlets and have become a source of criticism of the Saudi government. Riyadh has witnessed several rarely-seen demonstrations demanding the release of prisoners.

The trial was conducted by a special criminal court in Riyadh and the 16 terror suspects sentenced to a total of 228 years in jail. The suspects – 14 Saudis, a Yemeni and a Syrian – reportedly belong to a cell called Istiraha (Rest House). The Saudi members of the group will not be allowed to leave the Kingdom after their release while the foreigners will be deported after serving their sentences. All of the defendants have rejected the court verdict while the public prosecutor said the suspects deserved tougher punishment (Arab News, November 23).

While many jihadists are among those imprisoned on political charges in Saudi Arabia since 2003, the Salafi-Jihadists — in line with new soft-political rhetoric they presenting since the Arab Spring movements swept, focused on the prisoners issue as a new campaign strategy in Saudi Arabia.

Why Has the Arab Revolution Not Reached the Gulf?

A well-known contributor to jihadist internet forums with the pseudonym Hamzah al-Bassaam was interviewed by a jihadi website regarding al-Qaeda and the Arab Spring. On the question of why the Arab revolution has not reached the Gulf countries, particularly the country of the two holy mosques [i.e. Saudi Arabia], al-Bassaam replied:

Regarding the country of the two holy mosques, there is a good movement and what we’ve seen recently from the protests [demanding the] release of detainees and raising the voice of their families to the world is healthy evidence. It is important these protests continue…what prevents the movement [in Saudi Arabia from going further] are two things: first, the security grip and maltreatment of any dissenting voice or one calling for a revolution. Second is the official religious establishment, which the Sa’ud family places in the throats of those who want to lift the injustice and change the regime” (muslm.net, September 19).

On November 18, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula released an audio message from its Shari’a advisor, Shaykh Ibrahim al-Rubaish, entitled “A’la Khota al-Gharb” (Following in the Footsteps of the West) which focussed on the appointment of Prince Nayf Bin Abduk Aziz as Crown Prince in Saudi Arabia (Ansar1.com, November 18). Al-Rubaish, who had previously set political conditions to stop fighting the Saudi royal family, indicated the sort of changes that have occurred in the jihadists’ thinking as a result of the Arab Spring:

The most powerful way to release the prisoners is jihad because what has been taken by force can only be restored by force, but if this is not doable at least people [should] continue gathering in front of the Interior Ministry periodically until they find a solution to this issue [of prisoners to be released] and if some of them [are] imprisoned or force used against them they must be resilient. Some people should be on the frontline and sacrifice to [let others] enjoy [the victory] after them… the reality has proved the fact that the will of the people is unbreakable. [We need] a will to steadfastly confront the cronies of Ibn Sa’ud, similar to the will of the people of Tunisia [who] succeeded in the expulsion of [Zine al-Abidine] bin Ali, and the will of the people of Egypt in imprisoning Hosni [Mubarak], and the will of the people of Libya in killing [Mu’ammar] al-Gaddafi.

Al-Rubaish criticized King Abdallah bin Abd-al-Aziz’s decision to grant women the right to take part in the municipal and Shura Council elections, saying that this decision was considered "a decisive victory" by the media and "scored a goal" for the liberals. He added that "the liberals deem the king’s days a golden age because he follows in the footsteps of the West." Al-Rubaish believes this shows "the weakness" of the Islamists, who do not dare to advise the king or blame him for listening to the liberals. Al-Rubaish concludes his message by warning the Saudis against the "Westernization" of women, saying that this will open the door for giving leadership to women.

Conclusion

Although the Arab Spring movements created new challenges for both the jihadists and the Saudi state, the Saudis are more interested in preventing internal dissent inspired by youth movements while the jihadists feel challenged by the loss of their recruitment pool. It is unlikely that al-Qaeda will be successful in mobilizing young Saudis in political demonstrations as they do not have the tools required for public political mobilization. Therefore it is more likely that they will continue to rely on Yemen as a launching pad for attacks inside Saudi territories. However, developments inside Saudi Arabia indicate a level of frustration inside the kingdom which could lead to a political deadlock if the government takes further steps towards political reform.

Murad Batal al-Shishani is an Islamic groups and terrorism issues analyst based in London. He is a specialist on Islamic Movements in Chechnya and in the Middle East.

Note:

1. See “Saudi Arabia: Repression in the name of security,” https://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE23/016/2011/en/126dda68-1c2f-4f3e-b986-3efa797d3b9d/mde230162011en.pdf .