Kazakhstan’s Next Parliamentary Election May Lay Foundation for Eventual Presidential Succession

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 142

By:

In early July, Kazakh media reported on a new political initiative announced by a group of young activists headed by Olesya Khalabuzar (Informburo.kz, July 8). The group proposed the creation of a political party under the name “Spravedlivost” (“Justice”). This “new left” project seeks to build a multi-ethnic organization that would advocate building a society of equal opportunities. The project needs to attract at least 40,000 members to become officially registered as a political party and participate in the next parliamentary elections, scheduled for 2016.

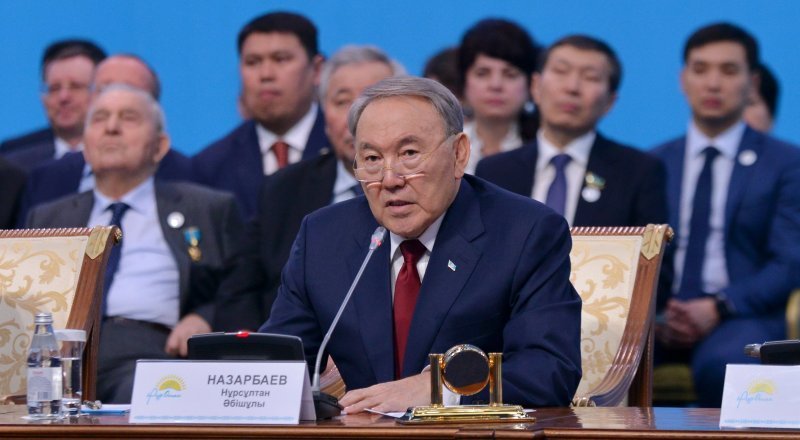

Most analysts expect that the parliamentary elections in Kazakhstan will be held in early 2016. Experts assign special importance to these elections because of the plans announced by President Nursultan Nazarbayev to grant more powers to parliament over the next five years (Ia-centr.ru, July 14). In fact, the timing of this transition is not entirely clear. During his presidential campaign in spring this year, Nazarbayev said that it would be appropriate to “decide on a new system of electing local executive bodies. A constitutional reform should be carried out stage by stage, envisaging redistribution of power from the President to the Parliament and the Government in accordance with our traditions” (Tengrinews.kz, March 11).

By late 2007, the presidential Nur Otan Party had become the only political faction able to pass the minimum 7 percent threshold to enter parliament that year. But in the 2012 election (which, along with the election of 2007, was held early), the Kazakhstani legislature ceased being a one-party experiment as two more parties joined the Majilis (lower chamber of the parliament): Ak Jol (representing the interests of big businesses) and the Communist Peoples’ Party of Kazakhstan (maintaining a leftist agenda and advocating for social justice). With some heretofore modest progress in promoting political participation and the president’s announced plans to strengthen the legislative branch, many thus expect that the political field in Kazakhstan may soon become a more interesting and competitive space.

Indeed, the domestic political agenda is becoming more diverse in Kazakhstan. In addition to the proposed Spravedlivost party initiative, perhaps most notable has been emerging demand for representation of more nationalist forces as well as a more active political movement for social justice (the Communist Party has largely failed this latter agenda and is increasingly seen as outdated). Kazakh nationalist forces remain generally fragmented but just recently have set up a Kazakh National Council that seeks to coordinate a unified agenda. Nationalist voices in Kazakhstan are, in fact, quite diverse and span a wide spectrum—from radical requests to grant special rights to the Kazakh nation, to more moderate demands to recognize the status of the language and history of Kazakhs (Kursiv.kz, June 29). As for a full-fledged nationalist party, its perspectives remain unclear as Kazakhstani legislation does not permit parties built on a nationalist, religious or racial basis. On the other hand, the government’s initiative to promote the nationwide patriotic idea “Mangilik Yel” (“Eternal Nation”) (Strategy2050.kz, March 4), combined with increased focus on Kazakh nationhood through jubilee celebrations of Kazakh writers and Kazakh historical milestones, give a stronger impetus to the nationalist agenda.

As opposed to the Kazakh nationalist project, Spravedlivost emphasizes its multi-ethnic inclusiveness and demands for greater social justice for all. At a time of low oil prices and constraints on government expenditures, the project will likely appeal to those suffering from inequality, corruption and limited economic opportunities. But the competition for votes between the nationalist and the multi-ethnic agendas, which may emerge, could be risky for Kazakhstan—particularly given Russia’s strong negative reaction to the rise of nationalist movements in those post-Soviet countries with large ethnic-Russian diasporas.

A number of other party initiatives were also announced this year, such as proposals for an Agrarian Party and a Democratic Party of Facebook (Sayasat, July 23). All these initiatives remain marginalized and have limited chances of succeeding in Kazakhstan, where the party-building process is strictly controlled from the top. Nonetheless, their existence highlights a growing demand in society for more active political participation.

Given the short period left before the start of the next campaign as well as the limited administrative and financial resources among the smaller parties and political forces, most if not all seats in the next parliament will probably remain in the hands of the three leading Kazakhstani factions—Nur Otan, Ak Jol and the Communists. And notably, the president himself did not include the initiative of strengthening the parliament in his “100 Steps”—a detailed plan for institutional reforms of the public service, judicial system, the economy, national identity and unity, and governmental accountability (Tengrinews, May 29). In his most recent interview, taken on his 75th birthday, Nazarbayev championed the executive over the legislature, saying: “presidential power didn’t oppress the people, but worked for the people.” He proclaimed he remains confident that parliamentary rule is often a source of disorder, like in Ukraine, Georgia or Moldova, which are “examples of post-Soviet parliamentary democracies” (The Diplomat, July 6).

Therefore, it is safe to expect that the plans to transition to a stronger parliament will not be fully realized for some time—most probably not until after the current president leaves power. While this next parliament will almost certainly resemble the current one, the composition of the parties elected in 2016 may accommodate new, more active personalities who enjoy higher status (Central Asia Monitor, July 9) and who may present a stronger counterbalance to the government. For example, President Nazarbayev’s daughter, Dariga Nazarbayeva, who is currently vice chairman of the Majilis, has a good chance of heading this legislative body after the next election. Smaller and newly emerging political parties or initiatives may have little chance of winning any seats in the next parliament, but their participation in the campaign should still diversify the debate on Kazakhstan’s most pressing issues.

Just as importantly, a parliament packed with more powerful members of the political elite will likely take part in the future succession plan. For President Nazarbayev, the main objective of succession is to ensure a stable system with loyal people in both the executive and legislative branches, capable of safeguarding his legacy. As the Kazakhstani head of state mentioned at the end of last interview: “my generation’s deeds will be remembered, because we are leaving a strong country for the future generations” (The Diplomat, July 6). Thus, for the foreseeable future at least, a strong parliament means a controllable parliament.