Lavrov Returns to Africa

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 91

By:

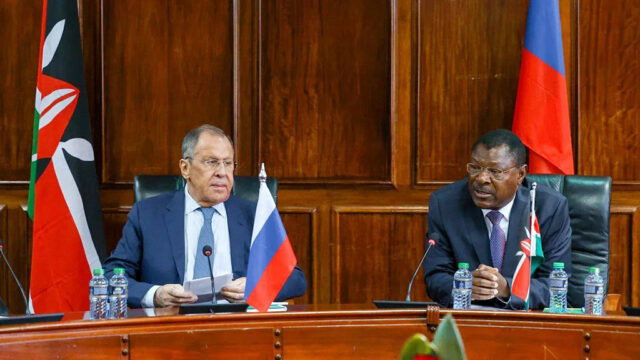

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has engaged in vigorous activity in Africa and Latin America over the past six months. He visited Brazil, Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua in Latin America, while in Africa, the Russian minister traveled to South Africa twice, Eswatini, Angola, Eritrea, Mali, Mauritania, Sudan, Kenya, Burundi and Mozambique. His visits to the African states have been presented under the pretext of preparations for the second upcoming Russia-Africa Summit in St. Petersburg starting on July 26 (RIA Novosti, April 21; Vedomosti, May 30).

The list of Latin American countries visited by Lavrov is no surprise. All have been close friends of Russia, and Brazil, with its new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, speaks in an appeasing mode in favor of Moscow’s aggressive war against Ukraine and its determination to dismantle the world’s security architecture (Gazeta.ru, April 7).

The same can be said about those African countries on the Russian foreign minister’s itinerary: Many have a positive history of relations with the Soviet Union (Angola and Mozambique) or currently host a significant Russian presence (Mali and Sudan). South Africa, for example, has been courted by Russian diplomacy for decades, resulting in it joining the BRICS economic bloc (loose grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). In August 2023, the country is set to host the upcoming BRICS Summit in Johannesburg—though it remains to be seen if Russian President Vladimir Putin will attend due to the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant against him (Business-standard.com, January 27; see EDM, April 19).

The Russia-Africa Summit is a serious achievement for Russian diplomacy, which is trying, with some success, to play on the interests of African countries in developing relations with significant centers of power to gain access to sources of funding, humanitarian aid and technical assistance, as well as to strengthen the political weight of the African states themselves (Rossiyskaya gazeta, October 24, 2019; Mid.ru, January 25, Mid.ru, February 7; Mid.ru, May 30). In this, the continent is keen to move beyond regional issues and raise its voice in addressing global challenges (Izvestia, May 25).

The natural desire of many developing states to diversify their foreign relations can be used by Moscow to its advantage, for example, to gain access to critical rare minerals in Africa, and, in something that has recently become increasingly important for the Kremlin, to drive wedges in the potential unity of the Global South in condemning Russian aggression against Ukraine. Obviously, Lavrov’s efforts in Africa and Latin America are primarily aimed at convincing those countries most exposed to the Russian perspective of the virtue of Moscow’s actions, or at least to try to ensure that these states do not join anti-Russian initiatives—for example, as part of the United Nations or regional organizations as well as Western sanctions (Mid.ru, June 1; May 30).

In this regard, South Africa’s peace initiative for the war, joined by several other African states, was likely conceived, inter alia, as a result of conversations with both Russian and Chinese representatives. The South African initiative is, of course, a product of Pretoria’s desire to contribute to peace efforts and thereby enhance its international reputation (Gazeta.ru, May 16). However, it lends itself well to Moscow’s unspoken request for the Global South’s intervention in the course of the war in Ukraine on the side of the aggressor. As far as one can tell from this initiative, its authors postulate that Russia has legitimate interests and concerns in Ukraine that must be taken into account—an idea quite coherent with the views expressed by Brazil and China (RBK, May 4).

It is becoming clear that, in the context of the war in Ukraine, such an approach initially suggests a significant head start for the Russian side in courting the Global South. Therefore, it would not be an exaggeration to say that it may have been Russian diplomacy that attempted to cultivate the South Africans’ desire to mediate and focus their diplomatic efforts in resolving issues the way Moscow wants.

Moreover, the peace initiative presented by the African countries will be a central topic at the upcoming Russia-Africa Summit. And it would be flippant to think that any reasonable and unbiased plan would be presented at a high-level meeting with Russia.

It cannot be ruled out that China, which has its own interests in Africa and has significant leverage in many countries on the continent, may also in turn provide some assistance to Russian efforts in contacts with the African states (Regnum, January 17, 2022).

For its part, Ukraine is trying to counteract these efforts. For example, Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba recently toured Africa promoting President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s peace plan—one that restores Ukraine’s full territorial integrity. Tellingly, Lavrov rushed off on his third tour of Africa shortly after his Ukrainian counterpart’s trip (Ukrainska Pravda, May 25).

Russia still has a great deal of “soft power” in the Global South, accumulated in its relations with developing countries during Soviet times. Obviously, the need to capitalize on this potential and formulate a comprehensive policy is recognized at some level in the Russian Foreign Ministry; Lavrov’s activities testify to that. Russian officials are also trying to play up old anti-colonial and anti-hegemonic narratives to promote Russia’s “alternative” world order (see EDM, April 23). Overall, it cannot be said that such an approach is being wholly rejected in Africa or Latin America.

Yet, Russian diplomacy is being challenged by the organic failures of the Putin regime—first and foremost, its inflexibility and sole focus on working with the centers of power, ignoring other actors such as opposition movements or civil society organizations. However, Moscow is counter-balancing these setbacks by actively using unconventional but quite effective tools to strengthen its influence in Africa, such as through mercenaries (e.g., the Wagner Group). Nevertheless, the question becomes how long will such a forceful resource of influence remain in control of the Russian leadership. And as its influence expands in the Global South, it would be naïve to remain hopeful that Russia’s troubles with limited resources will last, as this situation may still be countered by stoking anti-Western sentiments among developing countries, which takes extremely little to stir up.