Low Fertility Trap Fears Cloud China’s Release of 2020 Census Data

Low Fertility Trap Fears Cloud China’s Release of 2020 Census Data

The results of China’s seventh national census were released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) on May 11, after more than a month’s delay. NBS commissioner and deputy leader of the State Council Leading Group for the Seventh National Population Census Ning Jizhe (宁吉喆) announced at a press conference that China’s population was 1.41 billion, marking a slight increase of 72.06 million from the results of the sixth national population census in 2010 (NBS, May 11). The data reflected an average annual growth rate of 0.53 percent, down from 0.57 percent in the previous decade.[1]

Looming over the 2020 census results was a growing sense that the severity of China’s population decline was worse than previously thought. As recently as last December, a paper published by the government-affiliated China Population and Development Research Center (中国人口与发展研究中心, zhongguo renkou yu fazhan yanjiu zhongxin) predicted that China’s population would peak in 2027 (State Council Development and Research Center, December 23, 2020). Following the release of census results, even previously bullish experts revised their analyses to predict that China’s population would likely decline “as early as 2022” (Global Times, May 11).

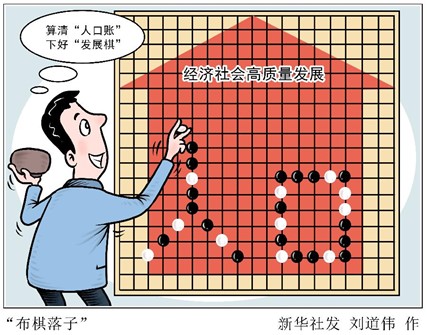

Such demography debates are not merely academic. Population decline will have major implications for macroeconomic policy making and development planning. State planners must address a transition away from China’s historic booming economic growth, which has been supported by a robust labor market and a long-standing “demographic dividend” (人口红利, renkou hongli), to a more mature economy driven by an “talent dividend” (人才红利, rencai hongli)—i.e., advances in technology and skilled labor—that can also support growing demands for more social support.

Census Results

“High Quality” Growth

First, the good news. China’s working population (aged 16 to 59) remained strong at about 880 million, and the average age is relatively young at around 38.8 (SCIO, May 11). Life expectancy continued to increase, and there were improvements in reducing illiteracy (2.67 percent) and increasing educational attainment. China’s infant gender disparities also became slightly more balanced over the last decade, with the sex ratio at birth improving from 1.18:1 (male:female) in 2010 to 1.11:1 in 2020 (NBS, May 11).[2]

Growing Urbanization

Twenty-five out of 31 provinces saw population gains, with Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong and Henan seeing the largest growth (The Paper, May 11). Much of this was driven by growing urbanization and migration to richer eastern regions, while central and northeastern regions saw population declines. The population in the three “rust belt” northeastern provinces of Liaoning, Heilongjiang, and Jilin fell by roughly 10 percent, or around 11 million people (NBS, May 11; Andrewbatson.com, May 12), demonstrating the unevenness of China’s development.

The proportion of the urban population increased by 14.21 percentage points, as China pursued aggressive policies to transfer underutilized rural workers to urban centers under poverty alleviation and economic modernization policies. China’s “floating population” (流动人口, liudong renkou)—defined as the population living in provinces outside of their household registration (户口, hukou)—increased by a staggering 69.73 percent (SCIO, May 11). Because access to social services is closely tied to residency, the census results further underscore the necessity for hukou reform. China’s urban authorities have begun taking steps to relax residency restrictions, and hukou reform was emphasized as a priority in the 14th Five Year Plan (FYP, 2021-2025) (South China Morning Post, May 13).

Birth Rate Decline

Ning Jizhe reported that China registered 12 million new births in 2020, marking an 18 percent decline year-on-year and a fourth consecutive annual drop, following a slight one-year increase after the relaxation of the One Child Policy in 2016. China’s fertility rate in 2020 was 1.3, far lower than the normal replacement level of 2.1 (last achieved in 1992) and also well below the expected rate of 1.8, leading one researcher to state that “China has fallen into the ‘low fertility trap’” (Caixin, May 11).[3] Ning suggested that the unexpectedly low fertility rate reflected effects from the pandemic. He also pointed to the higher fertility rate for second children and the fact that the number of children aged 0-14 grew by more than 30 million since 2010 as signs demonstrating the success of the relaxation of family planning policies (SCIO, May 11).[4]

Other Chinese demographers were more skeptical of the state’s success in boosting new births after 2016. Chang Qingsong (常青松), a demographer at Xiamen University, explained that “[the] Chinese have switched from policy-driven birth control to unwillingness to have children” (Caixin, May 17). Likewise, the popular economist Liang Jianzhang (梁建章) argued that low birth rates were both cultural and systemic: “China has the highest child-rearing costs of anywhere in the world, in turn leading to the lowest fertility rates in the world” (Caixin, May 13).

The census press release emphasized that China’s ethnic populations grew by more than ten percent (NBS, May 11)—a fraught claim amid accusations that China has committed genocide and crimes against humanity in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The provincial breakdown reported that the population in the XUAR was 25.8 million, representing an increase of 0.2 percentage points (NBS, May 11). But an independent study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) based on annual provincial-level data and released on the same day as the seventh national census results found that the birth rate across the XUAR fell by 48.74 percent between 2017 and 2019 following the implementation of “strike hard” campaigns aimed to “reduce and stabilize a moderate birth level” in 2017. (Ethnic minorities had previously benefited from exemptions to national family planning policies.) (ASPI, May 12). On May 13, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson complained that the ASPI’s reporting was “anti-China” and questioned its conclusions, saying that “between 2010 and 2018, the Uyghur population in Xinjiang increased by 25 percent” (PRC Foreign Ministry, May 13).

Related to the falling birth rate and growing urbanization, household size also fell below 3 people for the first time in history, which could have significant implications for parenting and elderly care (Yicai, May 12). The demographer Nicholas Eberstadt has argued that the transformation of the Chinese family structure will have broad economic ramifications: “It amounts to a radical change in a society historically defined by the importance of filial ties…It will impose financial burdens on individuals and limit their ability to move and pursue risky entrepreneurial careers” (Foreign Affairs, April 7).

Rapidly Aging Population

The number of people over 60 now accounts for 18.7 percent of China’s population, up 5.7 percent from 2010. The working age population fell by nearly 7 percent during the last decade. Ning Jizhe noted that more than half of the elderly population was aged 60-69 and still healthy enough to contribute to society; policymakers have sought to leverage the labor capabilities of this population by encouraging the (re)employment and support for older workers, as well as launching pilot programs for private pension funds to reduce strain on the national pension system (Xinhua, March 12; CBIRC, May 15). The aging development expert Yuan Xin (原新) was calm but pessimistic when interviewed about the census results. Yuan forecast that China’s elderly population would increase to more than 300 million in 2025 and 500 million by 2050, effectively doubling the current proportion of elderly people. “Population aging is the result of historical laws of population development which cannot be changed” (Guancha, May 11).

Conclusion: Consensus That Wide-Ranging Policy Changes Are Needed

Many of these population problems have long been anticipated by policymakers, but experts debate how best to ameliorate them. In the 14th FYP, Chinese leaders promised to implement a strategy to cope with the problems of low fertility rate and a rapidly aging population, including measures to develop an affordable child care system, reduce childbearing and education costs, and gradually raise the retirement age (Guancha, March 13).

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC)—usually more concerned with macroeconomic and monetary policy than demographics—released a working paper in April titled “Understanding China’s Population Transition and Counter-Measures” (关于我国人口转型的认识和应对之策, guanyu woguo renkou zhuanxing de renshi he yingdui zhice) calling for the full liberalization of family planning policies and more social programs to boost economic growth (SCMP, April 15). They concluded that policymakers should acknowledge that “China’s population conditions have already changed and the demographic dividends which were once a source of convenience require the repayment of a debt…education and technological progress cannot compensate for the decline in population” (PBOC, March 26). Similarly, the Global Times cited the independent demographer He Yafu (何亚福) as saying, “there is no doubt that China will fully lift family planning policy in the near future…[possibly] as early as this autumn during the [Sixth Plenum]” (Global Times, May 11).

Fully liberalizing family planning will not be enough. One expert panel suggested that Chinese state planners must focus on “how to make China more gender-equal and family-friendly society,” with suggestions ranging from increasing maternal/paternal leave, boosting affordable housing and childcare, increasing immigration and investing in technologies designed to help with workplace automation and elder care (ChinaFile, May 6). The popular economist Liang Jianzheng recently made a viral suggestion that the government should offer parents 1 million RMB ($156,000) for each newborn child, and calculated that the state would have to spend 10 percent of China’s current GDP (in cash grants, tax relief, or housing subsidies) to raise the fertility rate to the replacement ratio of 2.1 (Caixin, May 17). While the details of their suggestions are myriad, experts seem to agree that the state must be proactive and creative in dealing with the end of China’s “demographic dividend.”

Notes

[1] In addition to digitally collecting data for the first time, census takers also took down respondents’ identification numbers for verification purposes for the first time. Citing anonymous sources, the Financial Times had earlier reported that the census results would show China’s population had declined in 2020 for the first time since the Great Leap Forward (Financial Times, April 27; SupChina, May 11). NBS published a short statement rebutting the report the next day (NBS, April 29). After the results were released, commentary published in the state tabloid Global Times argued that the delay was due to the need to process more abundant data that had been collected digitally. It cited remarks made by the NBS’s chief statistician Zeng Yuping (曾玉平) saying that the population undercount rate was lower than international standards, and that the seventh census results were “true and reliable” (Global Times, May 11).

[2] The overall sex ratio was 105.07—only slightly changed from 2010 figures. The combined effects of of a cultural preference for male descendants and the long-standing One Child Policy (1980-2015) led to a gender imbalance that Chinese health authorities once called “the most serious and prolonged in the world” (Scientific American, January 21, 2015; Inkstone News, January 18, 2019).

[3] The “low fertility trap” is generally thought to occur after a nation’s fertility ratio falls below 1.5 and population decline becomes self-reinforcing.

[4] Critics noted that the census data appeared to show an excess of 14 million children in the 0-14 age group compared with annual birth statistics—although the data mismatch could have been due to a combination of reporting differences in the less-thorough annual statistics, the discrepancy of more than 5 percent led one longtime skeptic to call the 2020 results “the most unreliable census,” suggesting that the data had been artificially adjusted (Nikkei Asia, May 13; see also AEI, May 11).

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.