More of Georgia’s Muslims Try to Join Islamic State

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 71

By:

On April 2, two high school boys from Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge, populated by Muslim Chechens (known as Kists in Georgia), disappeared and later contacted their parents, notifying them that they were in Turkey. It is widely believed that the teenagers are heading for Syria, in order to join the Islamic State (IS; formerly known as Islamic State in Iraq and Syria—ISIS). Some unverified reports suggested that the two have already reached their destination (Civil Georgia, April 6).

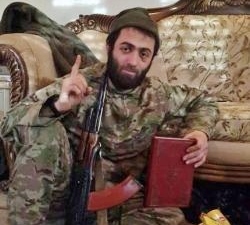

The two schoolboys’ departure for Islamic State–controlled Syria is beginning to look like an emerging pattern in Georgia. By some reports, about 50 Georgian citizens, most of them from Pankisi Gorge, are fighting for IS. And 11 of them have, reportedly, already been killed in the fighting (Ambebi.ge, April 4). Among those Georgian Muslims fighting in Syria is one of Islamic State’s highest ranking field commanders, Abu Omar al-Shishani (previously Tarkhan Batirashvili), who attracted worldwide attention for his tactical military acumen (see Terrorism Monitor, April 19, 2013).

As Georgia’s Ministry of Interior confirmed, many more Georgian nationals want to join IS. According to the interior ministry, it came across frequent cases of adults as well as underage men attempting to join IS, but those potential recruits were returned back to Georgia. The ministry, however, did not specify how, when or how many of them were returned (Civil Georgia, April 6).

Overall, there has been an observable trend in the gradual radicalization of Georgia’s Muslims. Specifically, in Pankisi Gorge, one of the most radical forms of Islam—Salafism (locally also referred to as Wahhabism)—has been gaining strength for a number of years among the local youth. The rise of the Islamic State certainly had an additional radicalizing impact in Pankisi Gorge, as well as in other parts of Georgia. For instance, several months ago, Georgian citizen Ahmed (previously Tamaz) Chaghalidze, who now fights along with IS, delivered via YouTube and the Georgian press lengthy threatening messages to all Georgians. He warned that if Georgians did not convert to Islam and join the Islamic Caliphate, they eventually would see bloodshed on their streets (Kviris Palitra, October 21, 2014, January 22, 2015; Rustavi 2 TV, January 18).

Ahmed Chaghalidze is from Georgia’s southwestern region of Adjara (Adjara Autonomous Republic) where Georgians were forcefully converted to Islam under Ottoman rule in the 17th–19th centuries. However, after Georgia gained independence, the Christian religion made a comeback in Adjara, as tens of thousands of Muslim Georgians converted back to Christianity. In the last seven or eight years, the tide has turned again. New mosques have sprung up in the region, one of which was attended by the above-mentioned Ahmed Chaghalidze. In fact, Chaghalidze specifically emphasized that the Adjara region would be entirely converted to Islam soon enough. As locals claim, besides Chaghalidze, many more local Muslims may have departed to fight alongside the Islamic State. They simply conceal their true whereabouts from their families, telling them that they have gone to work in neighboring Turkey (Rustavi 2 TV, January 18).

Major problems for Georgia—just as for any other country suffering from a similar phenomenon—can be expected when those radicalized Islamic fighters start to return home. Needless to say, it is highly unlikely that these returnees will take up a quiet, peaceful existence. Rather, they may attempt to radicalize and militarize others, thus bringing such violence and extremism home. The economically impoverished, militarily weak and politically unstable Georgia already faces a constant military and security threat from Russia; and it has few resources to fight a new domestic terrorist threat in the future. Such problems are more than likely to be exacerbated if they are met by relative indifference from stronger and richer Western partner countries such as the United Kingdom, France or Germany.

The Georgian government has already tried to take a step forward to address the ongoing outflow of Islamist fighters from the country (and their potential return). In January 2015, the cabinet submitted to the parliament a package of legislative amendments, which would criminalize participation in illegal armed groups in foreign countries, as well as “travelling abroad for the purpose of terrorism” (Civil Georgia, January 24). However, there are two problems with the legislation. First, the parliament still did not approve this bill, which illustrates that the Georgian political establishment does not take the threat of Islamic radicalization, however remote, seriously enough to act. Second, it is not entirely clear how the legislation will empower law enforcement to apprehend those radical Islamists who clandestinely traveled abroad and then returned home.

Overall, the situation regarding Georgia’s radicalized Muslims and their attempts to join Islamic State is quite serious. Certainly, it has not yet reached a critical point. However, the situation can gradually worsen if IS expands or even just maintains its hold on the large swathes of territories in Syria and Iraq, thus remaining a magnet for attracting recruits from Georgia. Therefore, the Georgian government will need to involve its strategic partners and their security services to design effective mechanisms that can prevent the growth of the emerging security threat to the country before it becomes unmanageable for Tbilisi.