Moscow and Tehran Building Closer Ties as Snowden Is Given Asylum

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 142

By:

Russia and Iran have become allies in the Syrian crisis, together providing military and financial assistance and advanced armaments that are essential to keep the regime of Bashar al-Assad in power. This increasingly close alliance has been giving more clout to those in Moscow who want to lift previously imposed sanctions and resume full-scale arms trading with Tehran. On August 12, President Vladimir Putin will be visiting the Islamic Republic to meet with the newly elected Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and also, probably, with Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. According to informed Kremlin sources, Putin will discuss in Tehran the Iranian nuclear program, possible new arms contracts and economic cooperation. According to Putin, “Iran is fully complying with IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency] rules” and there is no proof its nuclear program has a military dimension, “but there are some questions that may be answered within a friendly dialogue” (Kommersant, July 24).

The Iranian government seems keen to forge better relations with Russia to break out of its present isolation. Last February, during a meeting of the permanent intergovernmental Russo-Iranian economic cooperation commission in Moscow, Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak told journalists that the Iranians are inviting Russian oil and natural gas companies to participate in the development of Iranian resources and are ready to amend Iranian laws to allow partial Russian ownership of Iranian oil and gas assets. Russian oil majors Gazprom Neft and Lukoil have previously had joint projects in Iran but were forced to abandon them because of international sanctions. Today, Russian oil and natural gas majors seem to have little appetite to become involved with Iran closely once again, before punishing sanctions are lifted (Interfax, February 12).

The Russian nuclear industry state-owned monopoly Rosatom has built in Iran the country’s only major functioning nuclear power reactor in Bushehr on the Gulf coast and is at present partially in charge of its operation, as well as providing nuclear fuel. But Rosatom is currently eager to win contracts to build nuclear power plants in the European Union—in particular, the Czech Republic and Finland—and these aspirations could be hindered if Rosatom violates EU guidelines on nuclear cooperation with Iran. Rosatom says “the Iranians hardly have money to pay for any major nuclear power projects” and that the building of the Bushehr nuclear power plant that lasted more than 15 years resulted in financial loss. Rosatom officials told journalists they could consider at present any new nuclear cooperation projects in Iran only if ordered by the Kremlin “under political considerations” (Kommersant, July 24).

The Kremlin is dedicated to keeping Iran an important independent center of power in the region as a counterweight to the United States and its allies, while Russian arms traders and producers seem eager to resume full-scale arms exports. On July 9, 2010, Russia, together with other United Nations Security Council members, approved UN Resolution 1929 imposing sanctions on Iran, including a partial arms embargo, for continued uranium enrichment. Within the Moscow establishment, UN Resolution 1929 was never popular and has caused internal squabbles: The foreign ministry initially announced the UN sanctions allow the delivery to Iran of previously contracted five “divisions” or batteries of the S-300 PMU2 long-range anti-aircraft missile system worth over $800 million. This opinion was overruled by President Dmitry Medvedev, who on September 22, 2010 signed an ukaz (special executive decree) incorporating the UN 1929 resolution into Russian law, specifically stipulating a ban on selling S-300s. The foreign ministry was reprimanded, while Iran was repaid a cash advance of $167 million for the S-300s (Kommersant, January 11, 2011).

Iran, in April 2011, sued Russia for damages equal to some $4 billion in the Court of Arbitration in Geneva for canceling the S-300 contract (see EDM, July 26, 2011). The Geneva court has not made any decision yet, but recently Putin’s old-time KGB associate, the chairman of the mammoth state-owned defense corporation Rostekhnologii, which also incorporates Russia’s arms trading monopoly Rosoboronexport, Sergei Chemezov, told journalists: “Russia may lose the case in Geneva and is seeking an out-of-court settlement with Iran.” According to Chemezov, “The US is not supporting us in the case with Iran” (RIA Novosti, May 30). The Iranians announced they are ready to close the case “if their interests will be fully taken into account” (RIA Novosti, June 11). The arbitration court case could have been a smokescreen to allow Russian arms traders and producers, in cooperation with Iranian officials, to bypass sanctions. It has been reported in Moscow that the Kremlin has offered to sell Iran an improved version of the S-300VM, also known as Antey-2500—a long-range, anti-aircraft and medium-range ballistic missile defense system with capabilities comparable to the S-300PMU2—while Medvedev’s 2010 ukaz forbidding the shipment of S-300PMU2 units would be legally left intact (Kommersant, June 22).

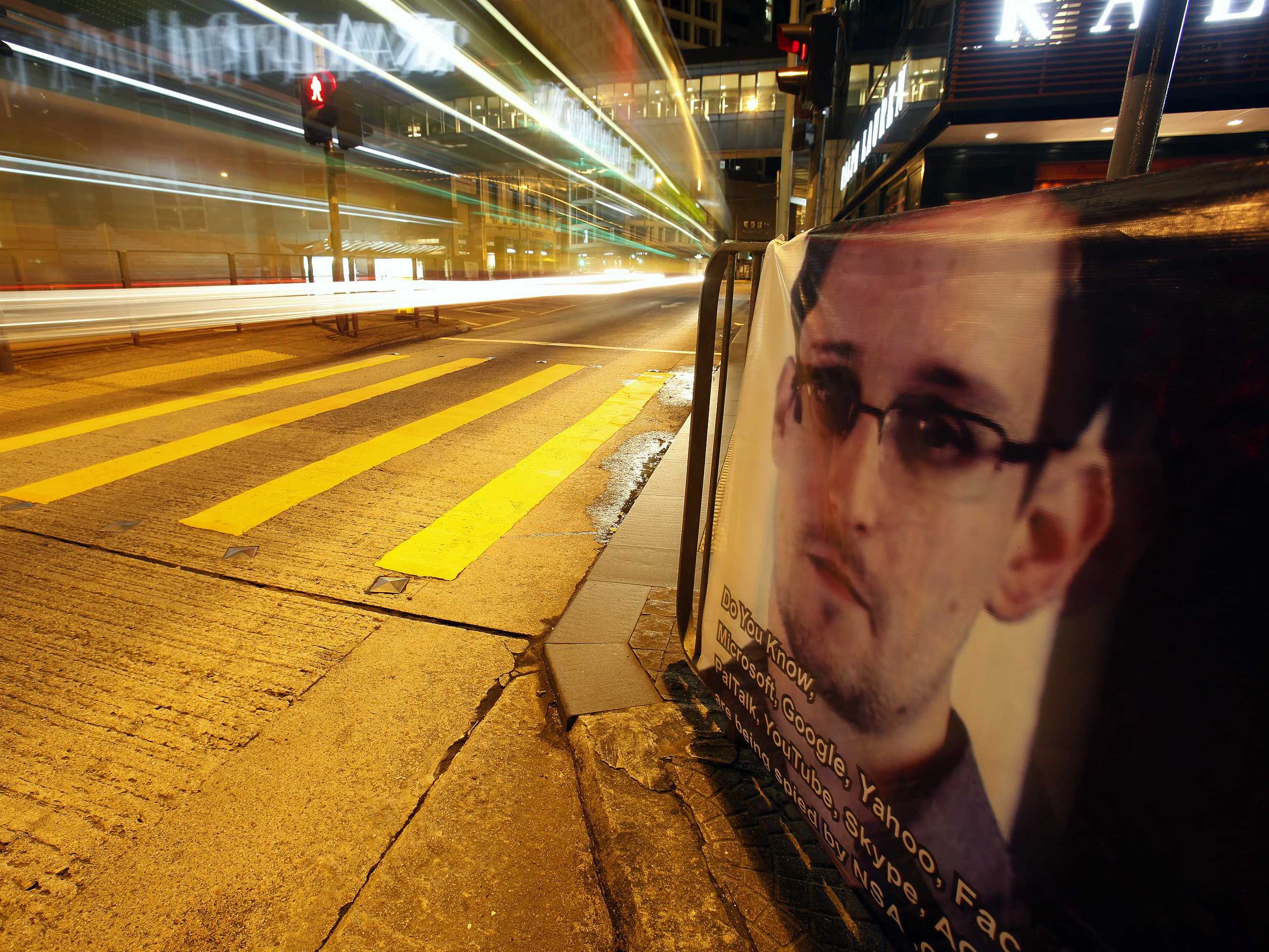

According to the Iranian Ambassador in Moscow Seyyed Mahmoud Reza Sajjadi, the offer of Antey-2500 to replace the S-300PMU2 “is, so far, only words—there are no agreements or talks” (RIA Novosti, July 31). Putin’s visit to Tehran could change that by fast tracking an agreement to resume the delivery of long-range S-300 missiles to Iran that have been designed during the Cold War for double use—defensive and offensive—with a capability to hit with precision high-value ground targets as well as aircraft. Putin’s Tehran visit is also coming directly after Russia, on August 1, finally granted fugitive US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden official refuge in Russia for a year with the possibility of indefinite extension (Interfax, August 1). Russian officials have expressed hope that the Snowden affair will not seriously hinder bilateral relations, but it could have a cumulative effect as Putin at the same time closes ranks with Iran. President Barack Obama’s visit to Moscow next month, planned as an extension of the G20 summit in St. Petersburg, could be curtailed or canceled, depressing US-Russian relations further. As growing internal political repression in Russia puts additional pressure on the US administration to be tough with Putin, both nations seem to be teetering on the brink of an extended confrontation.