Moscow Talks Business, Beijing Answers with Geo-strategy

Publication: China Brief Volume: 13 Issue: 22

By:

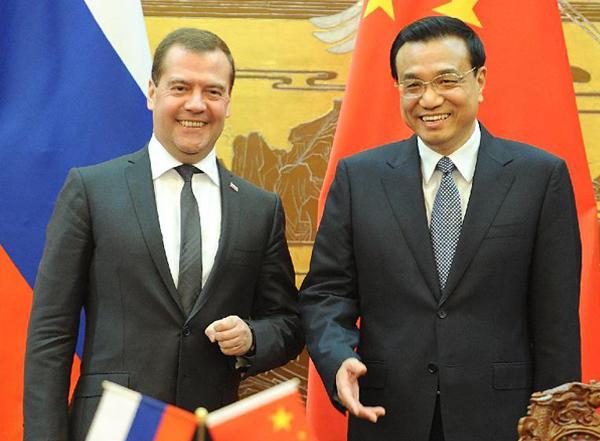

Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev visited Beijing on October 22 and 23, as Russia signed large energy, trade and investment deals with the Chinese government. Rosneft signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with CNPC to form a joint venture to explore several fields in eastern Siberia for oil and gas, with Rosneft taking a 51% share. The oil produced would satisfy local Russian demand for energy, with the rest going to China and other Asia-Pacific consumers (Xinhua, October 18). Rosneft also reached an $85 billion deal with Sinopec. This deal envisions an initial advance or down payment of 20-30% of the total, in addition to the $60 billion cited above from CNPC. At the same time, Russia’s Foreign Trade Bank, Vnesheconobank, signed several agreements totaling $1.9 Billion with the China Development Bank for the construction of important infrastructure projects in Russia (Kommersant Online, October 23).

These deals built on the earlier agreements signed by China and Rosneft in March 2013 about joint exploration in the Arctic (See Eurasia Daily Monitor, March 13). In that deal, Rosneft agreed to supply the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) with 365 million tons of oil for 25 years, worth $270 Billion. In return, CNPC has apparently made a pre-payment to Rosneft of $60-70 Billion. This amounts to 15 million metric tons of crude oil annually for 25 years, at just over $10 billion per year. This oil will probably flow through the existing East Siberia Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline to Daqing, China. Novatek, an independent gas producer, also granted CNPC a 20% stake in a liquid natural gas project on the Yamal Peninsula in the Arctic. CNPC will become an “anchor customer” and import 3 million tons of natural gas annually (Novatek press release, June 21; Upstream Online, June 21; Interfax, June 21).

While those deals are obviously motivated by energy and economic considers, Chinese press reports also highlighted their geopolitical significance. From the Chinese side, it seems clear that the visit’s purpose was to strengthen not only economic cooperation, but to enhance thereby overall geopolitical cooperation with Russia. As noted below, Russia does not appear to understand the relationship in the same way. The Medvedev visit built on the meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin at the annual APEC summit in Bali on October 7–8. At that meeting Xi said that “China and Russia had extensive common interests in the Asia-Pacific region. The Chinese side is willing to enhance coordination and cooperation with the Russian side and jointly help maintain security, stability, development, and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific region” (Xinhua, October 7).

The agreements with Medvedev were framed in the same way. Indeed, to hear Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang’s public statements, it would appear that China is seriously trying to go beyond the previous boundaries of its strategic partnership with Russia. He told Medvedev:

The concept of “top-level design” was not applied to international relations until the recent work forum on peripheral diplomacy (see “Diplomacy Work Forum: Xi Steps Up Efforts to Shape a China-Centered Regional Order,” in this issue). Introduced to the Chinese political lexicon by former President Hu Jintao, it is a concept borrowed from engineering, a kind of planning that “describes the major components and how they interact with one another to fulfill each requirement” (“Modeling the Architecture of a Software System,” Microsoft.com). As such, it appears to call for subordinating elements of the relationship, such as trading deals, to an overall plan. It is by no means clear that Russia has consented to—or even been informed—of this plan.

In this context it is noteworthy that Chinese press commentary on the Medvedev visit emphasized the geopolitical context within which it took place, comparing the meeting to recent visits by Indian Prime Minsiter Manmohan Singh and Mongolian Prime Minister Noron Aktanhuyag. The three Prime Ministerial visits have been cast in a single geopolitical context. So while the issues on the agendas of these visits were primary economic, taken in toto, these visits represent a continuation and acceleration of China’s diplomatic and peripheral strategy of alleviating tensions on its periphery to concentrate on domestic development and reduce threats by pulling these three states further into China’s orbit (People’s Daily Online, October 25).

These visits also signify China’s continuing, if not growing economic attractiveness to these governments as partners of China, at least in economic and trade issues. China is now the largest trading partner of all three of these countries, and thus the terms of trade with them are asymmetrically skewed in China’s favor. This economic power not only allows China to proclaim new initiatives like the Silk Road Economic Belt, that run contrary to their interests, but simultaneous offers China new opportunities to expand its relationship with them—allegedly on the basis of mutual benefit. Thus “Generally, China and the other three countries have chosen to seek common ground while reserving their position on any differences. The consensus on all sides favors enhancing strategic mutual trust and strengthening pragmatic cooperation” (People’s Daily Online, October 25).

Other commentaries observed that these ministerial visits display an enhanced peripheral diplomacy and are counters to the US rebalancing, or pivot, to Asia (Global Times, October 23). Thus, the commentaries observe, the enhancement of ties with these countries will reduce US influence, discouraging India from joining an anti-China balancing coalition, and inducing Russia to cooperate against such a group. The economic terms of the trade, investment, and energy deals are all quite large, but they fell short of Russia’s hopes, as it yet again failed to obtain the major natural gas deal it has sought for years. Despite Russian concerns about China’s dominant position as the largest single investor in the Russian Far East, Medvedev had to reiterate his and Putin’s previous statements that Russia welcomes more Chinese investment in the Russian Far East. Chinese investment in the Russian Far East is a source of major concern to Russian elites, who fear a risk of becoming excessively dependent upon that China and becoming a “raw materials appendage” (Bloomberg, October 13; Xinhua, October 23). As Dmitri Trenin, Director of the Carnegie Endowment’s Moscow office notes, “About 90 percent of Russian exports [to China] are hydrocarbons, while machinery accounts for less than 1 percent. Despite the Russian government’s professed desire to diversify the country’s exports, the energy element has only grown in the past few years. Russia has become one of China’s energy bases” (China Daily, October 25).

Indeed, we can get a sense of China’s geoeconomic and hence geopolitical objectives from the deals made with Medvedev and the agreements reached with India and Mongolia. It would appear that China is in some way perhaps rebalancing to Inner Asia, i.e. westward, and pursuing with redoubled vigor the goal of creating a huge continental economic bloc throughout Eurasia, thereby reducing Russian and Indian potential leverage and access to those countries and their resources, while attempting to draw them closer to Beijing diplomatically. Thus China Daily observed that these visits have yielded numerous bilateral agreements: “The significance of these visits will extend far beyond, especially when there is further progress on the proposed Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor and the Silk Road Economic Belt” (China Daily, October 23).

As the foregoing analysis suggests, China is trying to bring Russia into a closer partnership, but both sides are also determined to maintain a free hand on those issues that divide them. Nevertheless, there are many signs that Russian companies like Rosneft are losing their leverage vis-à-vis China as they take on huge amounts of debt from Chinese banks and companies. Meanwhile, the Russian Far East may be in danger of becoming wholly dependent on Chinese investment. On those issues where China is prepared to make deals with Russia or to gain further leverage, e.g. upon Rosneft, progress will occur, but Russia will remain decidedly the junior partner in these deals even as China rhetorically emphasizes Russia’s great power status.

Russian sources observed that the main goal of Medvedev’s visit was to promote an energy alliance with China (Kommersant, October 23). But while it is easy to see how both sides benefit in the short term from such an alliance, the geopolitical consequences of these deals appear to shift the balance of leverage toward China. Thus for the first time Russia has not only relented on giving China equity stakes in its oil fields as well as taking on huge loans that Rosneft must pay back. China has also gained large equity stakes in other important industrial sectors like potash by virtue of its being able to exploit Russian weakness caused by Moscow’s quarrel with the Belarusian government in Minsk (See Eurasia Daily Monitor, November 6). Clearly these deals’ economic terms translate into strategic and geopolitical leverage. Whatever the short-term economic benefit to Russia, it seems pretty clear that the lasting geopolitical advantage and initiative remain with China and that it, perhaps unlike Russia, knows what it wants and how to get it.

Dr. Stephen Blank is a Senior Fellow and resident Russia expert at the American Foreign Policy Council. Previously, he worked as a professor at the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, PA. The views expressed here do not represent those of the U.S. Army, Defense Department or the U.S. Government.