Murder That Revealed Truth

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 38

By:

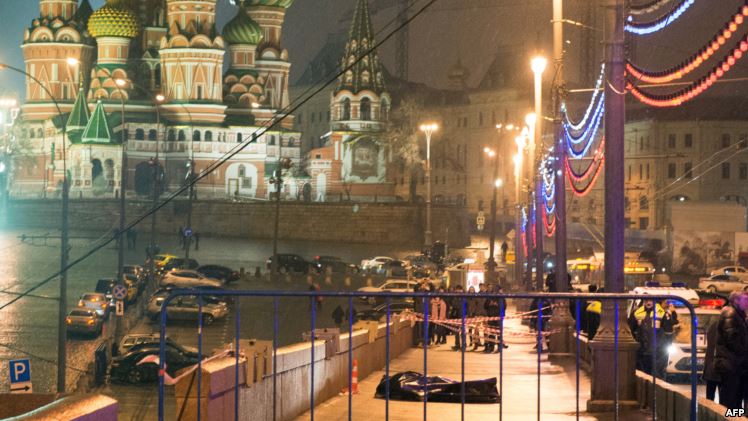

The photograph that hit millions of computer and smartphone screens late Friday (February 27) night, Moscow time, has instantly become a clear-focused image of what Russia has become amidst the Ukraine war: The night-time photograph in question shows a joyfully decorated bridge leading to the iconic St. Basil’s Cathedral and group of policemen standing hesitantly over a body, wrapped in a plastic sheet, lying on the pavement. The body was of Boris Nemtsov, a former deputy prime minister, and it was indeed too important to touch because Nemtsov was a man instantly recognizable in any crowd, even if Russian state TV had not shown his joyful smile for many years. To say that he was a fierce critic of Vladimir Putin’s regime would be an understatement: He was the face and the soul of Russia’s liberal opposition, marginalized as it is. In the last few weeks, he had focused his irrepressible energy on organizing a spring rally together with anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny, who remains under arrest for the crime of distributing leaflets about this rally in the Moscow metro (Moscow Echo, February 27).

President Putin found it necessary to qualify this “contract killing” as a “provocation” already at 3:45 on Saturday morning, perhaps seeking to pre-empt the resonance from the clearly politically motivated and demonstratively brazen murder (Kremlin.ru, February 28). It is a shocking coincidence that on the morning of Friday, February 27, Putin signed a decree on establishing the “Special Operations Forces Day” in order to mark the anniversary of the annexation of Crimea—carried out, as Putin later admitted, by Russian special forces units who were nicknamed the “little green men” when they first showed up on Ukrainian soil. And by late Friday evening, the surveillance cameras on the Kremlin towers recorded Nemtsov’s murder—a professionally executed “special operation” in its own right (Newsru.com, February 27). What made Nemtsov a perfect target for a political murder was the intense hatred that his defiant stance generated among the “patriots” who held a march in downtown Moscow on February 21, pledging to exterminate the treacherous “fifth column” of liberal opposition (see EDM, February 24; Slon.ru, February 27). Nemtsov did not mince words: in his last interview, he condemned “the insane aggressive policy of war with Ukraine, which is deadly for our citizens and for our country” (Moscow Echo, February 27).

The war has transformed the atmosphere in Russia into a foul and poisonous fog of jingoist aggressiveness, incessantly fanned by state propaganda. Putin’s popularity has risen sky-high on this nationalistic wave, but the odd thing about his system of power is that it cannot establish effective control over the ugly forces that he seeks to direct against the “specter of the Maidan,” allegedly conjured by the opposition, with presumed Western support (Novaya Gazeta, February 28). Waging a war requires a massive mobilization of effort aimed at achieving victory, but the “hybrid war” that the Kremlin is experimenting with brings about only a virtual mobilization of “patriotic” feelings, and nobody has a clue about what true victory could possibly look like. Putin’s arrogant and corrupt siloviki (security services personnel) cannot simply build a “police state,” which would require a great deal of work; and this leaves plenty of political space for criminal gangs, Kadyrovtsy (who are as untouchable by the law in Moscow as they are in Grozny), and various bands of “volunteers” with newly gained combat experience in eastern Ukraine (Ezhednevny Zhurnal, February 28).

It is no more possible for the Kremlin to discipline these extremists than it is to order Gazprom or Rosneft to reduce operational costs and become economically efficient. Instead of providing a modicum of stability for the crisis-stricken Russian economy, these crony-controlled “champions” are claiming priority access to the country’s dwindling financial reserves in order to cover their bad debts and continue projects that bring profits only to well-connected sub-contractors (RBC.ru, February 26). Nemtsov was an enemy of this system of institutionalized corruption, and Navalny keeps exposing the shameless stealing frenzy of the Kremlin courtiers. Mikhail Khodorkovsky delivered last week an irrefutable assessment of this ever-worsening crony-capitalism, which propels the Russian state to launch foreign wars in order to justify and hide the squandering of national wealth (Vedomosti, February 27). Khodorkovsky argued that the irreversible decline made it crucial to look beyond the current agony of Putin’s regime and to start working on a plan for what to do once Russia, imminently, hits bottom. But he probably believed Nemtsov was needed as the political driving force for such work (OpenRussia.org, February 26).

The Putinist system is, indeed, self-destructive, and it can claim many lives, including that of the courageous Nadezhda Savchenko, a Ukrainian soldier who has been holding a hunger strike for 80 days, protesting her illegal imprisonment in Russia (Novaya Gazeta, February 27). She has been elected a member of Ukraine’s parliament, but Putin cannot find an opportune moment to give the word for her release, fearing that it might look like him giving in to outside pressure (Moscow Echo, March 1). The fragile ceasefire in eastern Ukraine, negotiated in Minsk on February 12, is far from popular with Putin’s core “patriotic” constituency, which cries out for punishing Ukraine for its rapprochement with the West but shows no inclination to pay for rebuilding Donetsk and Luhansk. Putin has to lie about Ukraine’s impending collapse, while spinning a different lie about his commitment to the peaceful resolution of the conflict for his European peers. Such blending of incompatible falsehoods and distortions seriously undermines the big story of his firm leadership of a resurgent Russia.

Nemtsov was a voice in the wilderness of Russian propaganda and self-deception. And his murder has cut away multiple layers of lies in Putin’s “war is peace” story. Tens of thousands of people who marched last Sunday across the bridge, which the man who refused to live a lie had walked to meet four bullets, may never learn the truth about the hand that pulled the trigger. They know, however, where the responsibility rests for whipping up the hatred currently devastating eastern Ukraine and for turning murder into a “natural” continuation of the condemnation of Russia’s “traitors.” Putin’s regime has mutated into a war clique that cannot find any other foundation besides this irrational and self-destructive hatred; and it cannot stop with a “victory” in Debaltseve or with the murder of one individual who stood tall against their war. Yet, Russia is not inherently a country that hates, and there is hope that Friday night was the darkest hour before the dawn of consciousness.