New Strains Emerge in the Sino-Russian Military Relationship

Publication: China Brief Volume: 10 Issue: 21

By:

The military dimension of Sino-Russian ties, particularly arms sales, has been deteriorating since 2006-07. While that decline partly reflects the growing prowess of China’s defense industrial base, a major part stems from Russia’s growing apprehension about China’s growing capabilities and anger over its wholesale piracy of Russian weapons’ designs and ensuing competition with Russia for third party markets in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The unlicensed copying of military arms has made China a formidable military player and a redoubtable competitor with Russia in emerging defense markets. For instance, Russian experts profess surprise at how fast China has been able to copy the SU-27UBK (The Times of London, September 9, 2009). The combined effects of this mounting, albeit suppressed Russian anxiety (that is by the political leadership) about China’s improved military capabilities and anger about its unceasing piracy has apparently spilled-over to the public sphere.

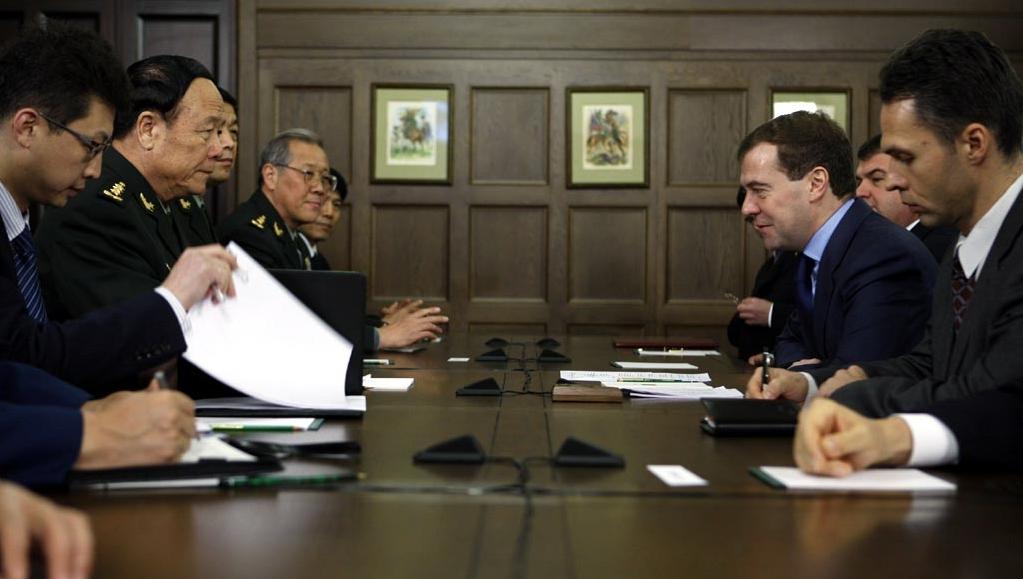

When General Guo Boxiong, vice chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) met in Moscow in late 2009 with his Russian counterparts, no substantial military technology cooperation agreement reportedly ensued form those discussions. Russian sources claimed that they were surprised by China’s positions, charging Russia with failure to abide by several bilateral military technology agreements with China. They replied that Russia could not sell China the engines for the Ilyushin-76 transport because the production facility in Uzbekistan lost its production capability. Chinese statements that Beijing would work directly with Uzbekistan meant that Russia would have to inject new investment into the Tashkent Aircraft Company of Uzbekistan, which was impossible.

China also said it would only import four SU-33 Fighters in the first phase where as Russia intends to export 40 of them. Thus, no agreement was reached on the fighters. Russian media also firmly opposed the export of Russian new generation military technology to China. Russia and China also differed on the provision to China of the technology for the KA-28 anti-submarine helicopter. Moscow held back on the automatic communication and navigation systems here that make it easy for the helicopter to keep in contact with its anchor ship. Yet China will now reportedly develop those systems alone (Kanwa Asian Defense, April 1-30). Although both sides agreed in principle to upgrade the two Varshavyanka and two earlier Kilo 636 class submarines that Moscow sold to China so they can fire 3m-54E anti-ship missiles, there was discord over whether they should be rebuilt in Russia as Moscow wanted or in China, as Beijing wanted. In the latter case, Russia would have had to invest in the Chinese factories to upgrade the systems, but refused to do so (Kanwa Asian Defense, April 1-30).

Although there was an agreement on selling China more Mi-17 helicopters and Al31F/FN and RD-93 aircraft engines, it is clear that the talks were frosty at best (Kanwa Asian Defense, April 1-30). Since then things have apparently gotten worse. China’s "land-based aircraft carrier" in Wuhan apparently shocked Russian and Western experts. At least some experts believe this vessel can actually be used as a platform for shipborne fighters to take off, i.e. as a real carrier (Kanwa Asian Defense, April 1-30).

In March 2010, Mikhail Pogosyan, General Manager of Sukhoi, made it clear that while Russia would develop the T-50 fifth generation fighter with India and export it to states like Libya and Vietnam, it would not sell it to China (Kanwa Asian Defense, June 1-30). The flourishing state of Russian arms sales to Vietnam and India—both countries with existing militaty tensions with China—suggests a desire on the part of Moscow to prevent China from obtaining the technologies and systems needed for this plane due to China’s cloning habit and out of concern over what it might do with the military capabilities of this fighter in the Indian Ocean (if not the Northwest Pacific) (Kanwa Asian Defense, June 1-30).

Moscow is also apparently blocking the export of Chinese fighters abroad. For example, it won the contract to sell Myanmar (aka Burma) MiG-29 fighters by agreeing to provide the RD-93 engines for the FC1-fighters that China would export to Burma (Kanwa Asian Defense, May 10-June 19). By intervening in this way in Burma (and also in Pakistan) over its purchase of Chinese JF-17 Fighter—which is a prime example of Chinese piracy of Russian designs—Moscow is making it clear that it is willing to block China wherever it can from selling fighters to potential Russian customers (Kanwa Asian Defense, May 10-June 19).

At the same time Russian experts like Ruslan Pukhov, Director of the Center for Analysis, Strategies, and Technologies, have launched a press campaign saying that China cannot copy Russian fighters because the results are hopelessly inferior (Interfax-AVN Online, June 4). Pukhov warned that China is not only trying to copy all of the Russian fourth-generation fighters it has received, but also their engines like those described above, which are still being sold by Russia to China (Interfax-AVN Online, June 4). In a similar vein, Russian defense officials are publicly belittling the capabilities of China’s J-15 Fighter as being inferior to the SU-33 Fighter (RIA Novosti, June 4). Therefore, even though Russia will sell China over 40 RD-93 engines this year for Chinese Fighters, it is clear that the competition and mutual suspicion of both sides in this aspect of their relationship is now out in the open (Interfax-AVN Online, January 11).

Implications

Russia’s desire to restrain the growth of Chinese acquisitions of military hardware and capabilities, and China’s penetration of third country markets emerges clearly from these episodes. Moscow’s actions speak to its growing anxieties about Chinese military power as does its recent military exercise (Vostok [East]-2010). Arms sales are the only area in which a visible competition if not rivalry between Moscow and Beijing has broken out. One can see it as well in Central Asia where discord flared in 2008 over the recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and again in 2009 when China broke Russia’s monopoly on gas pipelines out of Central Asia. There is also very good reason to believe that during the recent ethnic violence in Kyrgyzstan that China colluded with Uzbekistan to block a possible Russian military intervention in Kyrgyzstan and for the first time was able to prevail against Moscow in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), not just the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) (Central Asia Caucasus Analyst, September 1).

These strains on the Sino-Russian military relationship are becoming worse, not better despite all the rhetorical flourishes over a converging set of strategic interests. The leaders of these countries know it. This sense that not all is well in the bilateral relationship may lie behind Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo’s telling remarks to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in June 2010. Dai Bingguo observed that the international scene is undergoing complex and in-depth changes therefore the importance and urgency of comprehensively strengthening the bilateral ties with Russia have become "more conspicuous" (Xinhua News Agency, June 4). President Hu Jintao’s remarks to Lavrov paralleled this call for comprehensively strengthening the bilateral relationship and greater coordination and exchanges of views on major and sensitive issues in bilateral, regional and multilateral affairs to achieve greater coordination (Xinhua News Agency, June 4).

At the same time, Russia is losing out economically to China. Moscow had to accept Chinese loans of $25 billion to build the East Siberia Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO) that is soon to open. Similarly Moscow in 2009 tied the development of the Russian Far East to Chinese development plans for Heilongjiang province in Northeastern China, opening the way to Chinese economic colonization of the region. During his recent visit to China Russian President Medvedev actually pursued this policy further and invited Chinese investment in the new high-tech center in Skolkovo. In fact, it appears that either Russia or China will jointly co-produce military aircraft with Chinese investment or collaborate on investments in civilian aircraft that could easily become dual-use technologies even as China invests in high technology projects in Russia. Thus, Moscow appears to be blithely welcoming its economic integration into China´s economic network and ensuing further subordination of the Russian Far East to China as it become ever more dependent upon Chinese investments. According to Medvedev, "Never before have our ties been characterized by such a high level of mutual trust," Medvedev said, adding that his government welcomed Chinese investments in high-tech industries including aircraft construction" (Channel News Asia, September 27).

Given the accelerating rate of change in world politics and the growing disparity between Russia and China, it may well become more difficult for both capitals to preserve the synchronized nature of their relationship. This applies not only to the issues discussed here, but also to such other key issues as Iran, North Korea, international financial reform, the future of Afghanistan, and even future arms control negotiations. Given the increasing Chinese investment in the Russian Far East and in getting the prices it wants on Russian gas, the need for coordination might strike Beijing as being very important. Certainly, Moscow desperately needs to be working together with China rather than at cross-purposes with her. Yet, can it sustain that kind of partnership relationship with Beijing as its economy stagnates and as China leaps forward and brings in its wake the accompanying growth of Chinese military power and interests? Can the nature of the relationship continue despite Russia’s concern even as its neighbor subordinates Russia’s Asian economy-the future of the country-into its own economy?