Quad Restrictions: Addressing PRC Investment Concerns in the Indo-Pacific

Quad Restrictions: Addressing PRC Investment Concerns in the Indo-Pacific

Washington has recently taken a tougher tack to growing inbound investment from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) by strengthening the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), but its security partners in the PRC’s backyard have not all followed suit (US Congress, August 13, 2018).

In the United States, the primary concern is that the PRC is using foreign direct investment (FDI) as a Trojan horse: When PRC companies invest in critical sectors like energy, transportation, and communications in traditionally open economies, Beijing can gain access to critical technologies, data, and infrastructure it can use for military ends. Such investment can also set the ground for technology transfer—both licit and otherwise—and weaken longstanding alliances, put central governments at odds with their regional counterparts, and co-opt business interests as lobbyists for Beijing.

India, Japan, and Australia, America’s partners in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), face the same national security threats as the United States, but not all have responded by strengthening scrutiny of inbound PRC investment. In addressing these issues, Japan, which has managed to allow some inbound investment without exposing itself to national security risks, can serve as a starting point for its Quad partners.

Japan: Open for Business, Except to China

Despite their geographical proximity, PRC investment in Japan is not large—only $996 million in 2017 (Japan External Trade Organization, 2018). In recent years, PRC companies have invested in Japan’s finance, banking, retail and technology, and e-commerce sectors, with companies like Tencent, JD.com, and VIPSHOP recently establishing subsidiaries in Japan or partnering with Japanese companies. None of these investments have been in sensitive sectors, which is entirely by design (JETRO, 2017; PRC Ministry of Commerce, 2017).

Japan’s original foreign investment law, the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (FEFTL), passed in 1949, and placed strict boundaries on foreign investment. All inward FDI had to be filed with the Ministry of Finance through the Bank of Japan if the acquisition exceeded 10 percent of a company. FEFTL also required foreign companies looking to invest in critical industries like defense, energy, agriculture and livestock, financial services, high-tech, or certain types of manufacturing, to file with the Ministry of Finance six months in advance for national security review (Cabinet Secretariat, October 1, 2007). The FEFTL’s national security clause gave the Ministry of Finance and relevant sectoral ministries the authority to condition or cancel planned investment in cases where national security is impaired.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has pushed his government to throw off Japan’s historical closedness and do more to attract foreign direct investment. As part of his economic reform program, his government created an “Investment Advisor Assignment System” to make it easier for foreign businesses to consult with the Japanese government. The system assigns a State Minister to advise and support foreign companies that have invested roughly at least $180 million, have more than 500 regular employees in Japan, and have portfolios identified as strategic by the Japanese government. Seven of the nine companies that have been approved for the Investment Advisor Assignment System are from the United States. None are from the PRC (Invest Japan, accessed November 4, 2018).

This is partially due to distrust between the two countries: Roughly 30% percent of respondents in a December 2017 poll said that Japan should not cooperate with China’s economic plans, with only 8.6 percent saying Japan should cooperate with China (Genron NPO, December 2017). In the same poll, 66.5 percent of all respondents said that economic frictions between Japan and China was an obstacle to building China-Japan relations.

Japan has good reason to impede PRC investment in strategic sectors. When Japanese companies entered into joint ventures with PRC companies to develop high-speed trains, they ended up competing in third countries against their own technologies and designs, which had been stolen by their PRC partners (Wall Street Journal, November 17, 2010). Japanese businesses and the government have learned their lessons, with the honorary chairman of the Central Japan Railway Company saying that “the technology transfer to China was a huge mistake” (Japan Forward, August 18, 2017). As a result of these hard lessons, while PRC investment into Japan has increased, Japan’s pre-existing legal and bureaucratic frameworks have managed to balance national security concerns while not closing off the country from FDI.

Australia: National Security in the Economic Balance

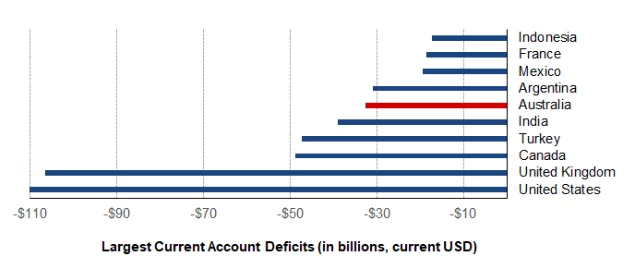

Australia has had difficulty striking a similar balance, but has recently moved in the direction of a stricter investment review regime. Foreign investment is critical in the Australian economy, which runs one of world’s largest current account deficits (World Bank).

The Australian economy—more so than most—cannot grow without foreign investment. Already, FDI supports 1.2 million Australian jobs—10 percent of the national workforce—and nearly 25 percent of Australian industry and exports (Australian Trade and Investment Commission). PRC investment has surged in the past decade, growing more than 20 percent since 2012 to become the ninth largest source of investment in 2017 (Australian Trade and Investment Commission). Australia also receives significant amounts of investment—90 billion dollars (116.6 Australian dollars) from Hong Kong, Australia’s fifth largest foreign investor. Much of Hong Kong’s outbound investment originates from the PRC, although it is difficult to determine the exact amount. Combined PRC and Hong Kong investments in Australia is almost as much as that of Japan, Australia’s fourth largest investor.

Reflecting these realities, Australia until recently maintained a relatively permissive foreign investment regime. Unlike CFIUS, which can block transactions on its own authority, Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) only advises the country’s Treasurer on major foreign investment proposals. The final decision lies with the Treasurer, who can—and often has—delegated this authority to lower-level officials. In addition, until 2017, the Australian Treasury evaluated foreign investment proposals on an ad-hoc basis, meaning that Australia did not have a preemptive list of critical sectors where foreign investment is limited or restricted for national security reasons.

Australia has seen persistent tension between the security-minded central government in Canberra and state governments eager to strike deals with PRC investors. In 2015, the Northern Territory government signed a 99-year lease with Landbridge, a PRC company with ties to the the People’s Liberation Army and Chinese Communist Party, for the Port of Darwin, which also hosts more than 1,000 US Marines and the US military ships that supply them (Guardian, October 13, 2015).

Although major foreign investments should be subject to FIRB approval, the Northern Territory government and Landbridge exploited a loophole wherein state and territory governments did not require Canberra’s approval before selling off their critical infrastructure. The proposal was reviewed only at the lowest levels of Australia’s Department of Defence (The Australian Financial Review, May 2, 2017).

The deal prompted then-US President Barack Obama to raise the issue with former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull (The Australian Financial Review, May 10, 2016). Australia’s central government officials shared US concerns: The lease only guarantees the Australian Navy full port access for 25 years of the 99-year lease, and Landbridge’s previous investments in a Panamanian port coincided with Panama’s shift of diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC (Financial Times, July 18 2017).

Soon afterward, in March 2016, the Australian government formalized stricter foreign investment rules, amending the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Regulation of 2015 to make all critical infrastructure acquisitions—including those from state and territory governments—subject to FIRB review (Australian Treasury, March 18, 2016).

In August 2016, the New South Wales government attempted to sell Ausgrid, one of Australia’s leading electricity distributors, to State Grid, a Chinese state-owned company and the largest utility in the world (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, July 12, 2016). Canberra rejected the sale on national security grounds, as Ausgrid also operates Pine Gap, a joint US-Australian intelligence facility that monitors nuclear flares in Eurasia (Sydney Morning Herald, October 21, 2016; Sydney Morning Herald, May 28, 2018).

Soon afterwards, in January 2017, Canberra created a Critical Infrastructure Centre to preemptively advise FIRB on national security matters, and to maintain a confidential register of high-risk assets and sectors like energy, telecommunications, and transportation. To support the Critical Infrastructure Centre, the Australian Parliament passed the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act of 2018, which imposes reporting requirements on owners and investors of critical infrastructure; grants the Department of Home Affairs the authority to request information from owners, operators, and investors in critical infrastructure; and allows the government to directly intervene in critical infrastructure to mitigate national security risks (Critical Infrastructure Centre).

Although Australia’s revamped approach to foreign investment played a part in Canberra’s decision to kill the Ausgrid deal, it is too early to tell whether the changes will have the overall desired effect, as state and territory governments still seem eager for Chinese investments—even those that come with PRC ties. Most notably, the state of Victoria, recently bypassed Canberra to sign a memorandum of understanding committing the state to participation in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (Australian Financial Review, October 26, 2018). The state government initially hesitated to release the text of the agreement publicly; when it finally emerged, the language bore many hallmarks of having been directly translated from Chinese, indicating that the Victorian government had likely done little to no negotiating with their PRC counterparts over its contents prior to signing.

India: Worst Friends, Best Enemies

As with Australia, China has emerged as one of India’s fastest growing sources of FDI; PRC FDI in India has more than doubled in the last decade (UN Conference on Trade and Development). Unlike Australia, however, New Delhi has adopted a welcoming attitude toward PRC investment, belying the sometimes-antagonistic geopolitical relationship between the two countries. Even after a two-month military border standoff last year, India has continued to loosen restrictions on inbound PRC FDI (The Economic Times, July 12, 2018). So far, PRC investment has flowed primarily into India’s digital start-up sector, but New Delhi is in the process of dismantling protections that would prevent Beijing from making investments in critical sectors like defense, telecommunications, and infrastructure.

After its independence, India maintained a restrictive FDI policy that favored domestic ownership and curbed the outflow of limited foreign exchange reserves. The Indian government only began to liberalize its FDI policy in the 1990s with the New Industrial Policy of 1991, which opened nearly all sectors to foreign investment, allowing foreign ownership of up to 100 percent in some sectors. Today, most FDI enters India through the “automatic route”—that is, without government approval. Elsewhere, like the atomic energy sector, FDI enters by the “government route,” in which foreign investment requires government approval. The Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) of 1999 delineates which sectors fall under each route, but foreign investment is generally permitted unless expressly restricted (Observer Research Foundation).

Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014, his government accelerated the dismantling of India’s foreign investment restrictions, a tacit acknowledgment that India’s lack of domestic liquidity has stifled its economic potential.

In May 2017, India abolished its CFIUS equivalent, the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB), underscoring the desire to speed FDI applications through the government route. The change devolved approval of FDI proposals to relevant government departments. Although FIPB had proved to be slow and unwieldy, some experts question whether India’s government ministries have the capacity to enforce the relevant restrictions, and whether or not India may be compromising its national security in its pursuit economic growth (Reuters, May 24, 2017; Livemint, May 25, 2017).

More broadly, as part of the “Make in India” initiative, the Modi government has relaxed restrictions in critical sectors like defense, which now allows foreign investment of up to 40 percent of shares under the automatic route, with larger shares possible through the government route (National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency). The Modi Administration’s Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) has also promoted opportunities for foreign investors in critical sectors. In the power sector, DIPP has highlighted investment opportunities in Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, an access point that an adversary could compromise to mount a cyber attack. India also now allows 100 percent foreign ownership of non-nuclear power generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure without prior approval (Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion).

India, perceiving the PRC as a geopolitical threat, has so far boycotted BRI. However, while New Delhi has gone to great lengths to dissuade its neighbors from accepting PRC foreign investment, it continues to loosen its own FDI policy. Without sufficient consideration of national security, New Delhi risks exposure to the same problems that wrong-footed Canberra.

Investing in the Alliance

The PRC will continue to look abroad to acquire goods and services—and in some cases, leverage—in critical sectors. America’s Indo-Pacific allies are in a precarious position, looking to the United States as their primary security partner, while fostering growing economic links with the PRC. Although their economies vastly differ, America’s allies in the Quad could each benefit a closer look at their foreign investment policies, seeking a practical balance between economic considerations and the national security concerns that often underwrite Chinese investments. While Japan’s system is not perfect, there is room to share best practices with other Quad partners, such as India, whose system appears vulnerable to predatory inbound investment that would undermine their alliance.

Ashley Feng is a research assistant in the energy, economics, and security program at the Center for a New American Security. She can be found on Twitter @afeng79.

Sagatom Saha is an independent energy policy analyst based in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in Foreign Affairs, Defense One, Fortune, Scientific American and other publications.