Renewed Expressions of Belarus’s Stability

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 46

By:

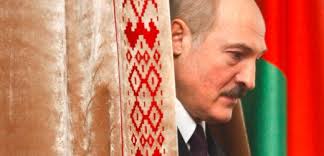

During a meeting with the Belarusian police directorate, President Alyaksandr Lukashenka once again declared that no disturbance of public order will be tolerated in the country. He also suggested that Belarus must be able to push back against a potential export of radical nationalism. Moreover, the Belarusian president argued that Western countries have finally realized the value of political stability and security, which Belarus embodies, and decided to engage the East European country (Tut.by, March 5).

Meanwhile, politically active Belarusians continue to debate the issue of “national consolidation”—or rather, the lack of it—but there is no sense of urgency related to those debates. According to Andrei Kazakevich, the director of the Minsk- and Vilnius-based “Political Sphere” Institute, consolidation around one person is a vulnerable option to begin with. Still, he believes that Belarusians of different persuasions should look for the most basic values pertaining to Belarusian-ness, values that could potentially unite them. According to Alexei Bratochkin, the editor of Novaya Europa news and analysis portal, it is unlikely that anything short of an external military threat would suffice for the current political regime to consolidate Belarusians (Tut.by, March 4).

On practical issues, however, Belarusians display further unwillingness to speak with one voice. For example, soon after the chairman of the Belarusian Pen Center, Andrei Khadanovich, opined that it is not worth discriminating against Belarusian authors who write in Russian, two other prominent members of the Pen Center voiced their categorical disagreement. The issue revolves around the assertion that unless linguistically Russian authors are members of the official writer’s union, they lack domestic structures to protect them. And although Svetlana Alexievich—a prime example of just such an author—may not require that sort of support system in view of her honoraria and popularity abroad, other Russian-language writers not loyal to Lukashenka may need it (Svaboda, March 8).

Yet another expression of a fundamental disagreement can be found in Yury Shevtsov’s response to this author’s quoting of Shevtsov’s 2005 statement—to the effect that competing interpretations of World War II–era developments have divided Belarusians into mutually opposed segments (see EDM, March 6). A prominent political commentator, Shevtsov, revealed that by now his standpoint has radicalized. Instead of thinking in terms of two equally valuable national narratives, as he did ten years ago, he now thinks that one of them, the Westernizing narrative, has morphed into a dead branch—it slightly poisons the entire Belarusian cultural tree, but not to the extent as to jeopardize its further growth. In other words, following the retreat, in 1944, of those Belarusians who collaborated with the Nazi German occupying authorities, Belarus’s national development along the lines of the traditional East European blueprint of linguistic nationalism became impossible, Shevtsov believes (Facebook.com/yury.shevtsov, March 7). That, as some would suggest, made distancing from Russia problematic.

In terms of Belarus’s present-day relations with its large eastern neighbor, Russia has not (yet?) issued a new loan to Minsk, even though the latter needs $2.5 billion in financing (see EDM, February 26). However, President Vladimir Putin did recently award Lukashenka the Alexander Nevsky medal, a distinction introduced by Katherine I to distinguish foreigners who contributed to strengthening ties with Russia (Lenta.ru, March 3). Also, following the Lukashenka-Putin meeting in Moscow earlier this month, the two sides reiterated the desire to set up a common visa space (Svaboda, March 3). Should it be implemented, foreigners in possession of a Belarusian visa will be allowed to freely enter Russia, and vice versa. Also, those on Russian travel sanctions will not be able to enter Belarus, and vice versa. The issue has been debated for quite some time, so it will not be surprising if no action is taken yet again.

While Minsk’s relationship with the West begins to gradually improve, the Russian media continues to express worries about Belarus’s potential geopolitical and brotherly infidelity. As a result, Minsk has initiated a new routine of dispatching Belarusian pro-government experts to Moscow-based political TV talk shows with the task of defending Belarus from such accusations. An episode of one such talk show, titled “Belarus’s Turnaround” (i.e., allegedly, from Russia to the West) was aired on the Moscow TV channel TVC, on March 3. The Belarusian side was represented by four pundits, including the aforementioned Shevtsov. The gist of their message to the Russian audience was that “our” nationalists (i.e., Belarusian Westernizers) are weak and have no clout in Belarusian society and that the status of “our” relationships with the West falls short of the one enjoyed by Russia and Kazakhstan, two Eurasian Union partners of Belarus. Ultimately, these speakers argued, Belarus’s alleged turnaround is a chimera, so Russians need not worry (TVC, March 3).

Though perhaps short of a “turnaround,” the improvement of Belarus’s relations with the West, nevertheless, continues, albeit without visible breakthroughs. Thus, Eric Rubin, US Deputy Assistant Secretary of the State, opined during his early-March 2015 visit to Minsk that by improving relations with Belarus, the United States actually upholds its independence. Rubin expects Belarus will release the remaining political prisoners, allowing the rest of US sanctions on the country to be removed (Tut.by, March 3). Moreover, writing for Tut.by, Belarus’s most visited non-government news and analysis portal, the political commentator Artym Shraibman observed that Minsk is holding firm in regard to the Western demand to release political prisoners. Moreover, one of them, Nikolay Dedok, has just received an unexpected one-year extension of his prison term because of his alleged violation of the prison dress code. Minsk, however, has noticed that the value of political prisoners’ release in the overall gambit with the West has declined on the West’s own initiative; so Minsk is in no hurry to oblige, Shraibman believes (Tut.by, March 2).

At the same time, few problems still remain to be resolved in the ongoing negotiations about the simplification of the visa regime with the European Union. It is likely that the final decision will be announced at the upcoming Riga summit of the EU’s Eastern Partnership (Tut.by, March 3).

By all appearances, developments in Belarus have once again entered a kind of stasis—that is, a state of equilibrium caused by opposing forces. Considering the current armed conflict to the south of Belarus and political assassinations to its east, such stasis is no small achievement for Belarus’s political regime.