Special Issue: Sino-Indian Relations

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 1

By:

As Editor I have the pleasure of introducing our special issue on Sino-Indian Relations. The issue brings together a number of top China-watchers to examine the current security situation between the two countries.

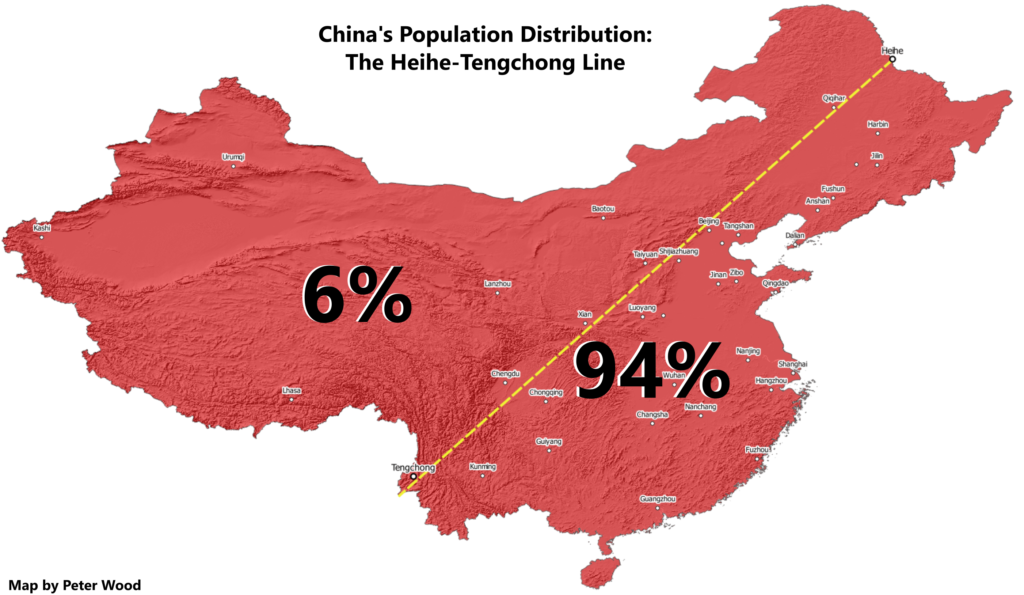

China is attempting to conquer this space, throwing increasing numbers of highways and rail connections across Western China to further bind it to the ethnic-Han core. It recently inaugurated connections between Shanghai and Afghanistan along the path of the old Silk Road and sent the first convoy of trucks down the Karakorum highway through Xinjiang and Pakistan to Gwadar, the port it helped expand on the Indian Ocean. Both these land and sea connections are of vital importance as China, under Xi’s direction attempts to continue its incredible growth by expanding into markets across the Eurasian land-mass. India itself offers great opportunities for Chinese companies. It is on track to be the most populous nation on earth by 2022, and is already a major destination for Chinese exports. [1]

This reinvigorated investment in the west will make getting an India policy right even more important. The two nations are attempting to heal old wounds, and both Presidents Modi and Xi have visited each other’s nations with pledges of expanded trade and cultural exchanges. But high-level visits such as Xi Jinping’s in 2014 have similarly been marred by incursions into Indian-claimed territory by groups of PLA soldiers, albeit small ones. The relationship is further complicated by China’s close partnership with Pakistan, its “all-weather strategic partner,” which regularly purchases large amounts of weapons from China, such as its 2015 deal to purchase eight submarines for $5 billion (SCMP, April 26, 2015).

Starting this issue, Kevin McCauley provides a snapshot of China’s newly created Western Theater Command (WTC), which has responsibility for the border with India as well as the complicated borders with Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. McCauley notes that the WTC’s geography creates its own challenges, forcing the PLA to be ready to fight in high mountains and deserts. Long distances compound the issue of terrain, making coordination of various units more difficult. The WTC’s primary conventional role is focused on India, but it also faces social stability and counterterrorism missions. This recently came into play during the first week of January, when units in Hotan (和田) were involved in a counterterrorism operation that resulted in the deaths of three terrorists (SCMP, January 9). As the PLA modernizes and introduces advanced air defenses and better tanks to units, it will need to improve both its ability to communicate amongst itself and the roads and other logistics infrastructure it needs to sustain a protracted campaign in a conflict with India.

Oriana Mastro tackles the complex issue of China’s intentions toward India, examining how Chinese press responds to India’s own modernization and military exercises. She notes that while India has made its own major investments in border infrastructure, mountain warfare units and its navy, China primarily remains focused on Japan, Taiwan and the United States.

Sudha Ramachandran observes that culturally and politically, Tibet is a sore point for China and India. After the Tibetan Uprising in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to northern India, setting up a government in exile in Dharamshala, India. China’s reaction to the Dalai Lama’s upcoming visit to Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh, which China claims, is illustrative of some of the underlying political issues at stake. Geographically the region is critical to security in India’s Northwest but also sits astride an important valley connecting greater Tibet to the south. The Dalai Lama’s visit—particularly given his advanced age and China’s hope that his successor will accept Tibet’s Chinese-defined borders has the potential to significantly inflame relations. India’s support of the Tibetan government-in-exile will continue to complicate this relationship.

Finally, Jonathan Ward examines Sino-Indian competition at sea. Both China and India’s navies are expanding at a rapid rate and are improving military facilities on their peripheries to better exert maritime control. Heavily dependent on exports for their economies and on imported petroleum to keep those economies running, both see their Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs) as core vulnerabilities. In turn, they are cultivating allies on each others’ doorsteps with India improving its relations with Vietnam, and China investing significantly in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Mauritius.

From the Himalayas to the Straits of Malacca, China and India are set to compete militarily and economically. Both nations have important roles to play in the global economy as developing nations transitioning to more mature economies. I hope this special issue will lay some useful groundwork for understanding their strategic competition over the next few years.

Peter Wood is the Editor of China Brief. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterWood_PDW

Notes

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. P. 4 https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/Key_Findings_WPP_2015.pdf