State Goals, Private Tools: Digital Sovereignty and Surveillance Along the Belt and Road

State Goals, Private Tools: Digital Sovereignty and Surveillance Along the Belt and Road

Executive Summary:

- Beijing promotes digital sovereignty in its engagements with other countries but with the caveat that it can maintain access to partner countries’ digital systems.

- Leaked documents from cyber contracting firm iS00N indicate a focus on One Belt One Road partner countries, targeting critical systems, including telecoms, government ministries, and financial institutions.

- A new paradigm of using nominally private firms allows Beijing to put distance between its inclusive rhetoric of “win-win cooperation” while companies hack partner countries’ infrastructure at the direction of its security services.

In November 2024, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) mouthpiece the People’s Daily published an article amplifying Beijing’s commitment to the “high-quality development (高质量发展)” of the One Belt One Road (OBOR; 一带一路) initiative (People’s Daily, November 28). In particular, the article emphasized digital cooperation and technological standards. This aligns with Beijing’s public promotion of encouraging international cooperation through UN development mechanisms. It is at odds, however, with the work of commercial contractors integrated with the public security apparatus of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that are tasked with systematically compromising PRC partner nations’ digital sovereignty.

Documents from iS00N Information Technology (安洵信息), a PRC cybersecurity contractor that was the subject of an extensive leak in February, reveal how private firms serve as instruments for expanding the PRC’s cyber control while maintaining diplomatic deniability for such actions (China Brief, March 29). These documents suggest a particular focus on OBOR countries. As Beijing expands its digital presence through initiatives such as the Global Data Security Initiative (全球数据安全倡议) and regional cooperation frameworks, partner nations face increasing pressure to balance the benefits of PRC technological investment against growing risks to their sovereign interests.

PRC Extends Influence Through Digital Sovereignty Framework

The Digital Silk Road (数字丝绸之路) initiative, launched in 2015 as a key component of OBOR, is in part a strategy for Beijing to build next-generation digital infrastructure—and thus increase influence and control—in developing markets (Belt and Road Portal, November 30, 2023). This digital dimension encompasses investments in telecommunications networks, artificial intelligence capabilities, cloud computing infrastructure, and smart cities, fundamentally reshaping the digital architecture of participating nations. At the infrastructure level, PRC firms have established 34 cross-border terrestrial cable networks and multiple submarine cables connecting to Russia, Mongolia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Central Asia, and South Asia while deploying nearly 1.9 million 5G base stations covering 3.3 billion people (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences [CASS], January 29). This physical expansion is reinforced through institutional arrangements. Beijing has signed memoranda on digital economic cooperation with 18 countries and established bilateral e-commerce mechanisms with 30 nations since 2017 (Cyberspace Administration of China, April 10). Beijing also uses the Digital Silk Road to promote technical standards and governance frameworks, positioning itself as a leading architect of the global digital order.

The PRC has strategically reframed its digital expansion within the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (UN, June 5, 2019; UNDP; PRC Permanent Mission to the UN, September 15, 2023). Rather than explicitly promoting the Digital Silk Road brand, Beijing presents its digital infrastructure projects as essential contributions to global development goals. This positioning serves multiple purposes. First, it frames PRC digital infrastructure as a global public good rather than an extension of national interests; second, it deflects criticism of the country’s technological expansionism; and third, it creates institutional momentum for the PRC’s technical standards through UN development mechanisms. The framework’s effectiveness stems from what PRC analysts term “hard connectivity (硬联通)” through infrastructure and “soft connectivity (软联通)” through institutional arrangements (CASS, January 29). Recent refinements to the PRC’s cross-border data governance policies, including measures for “high-level opening up (高质量开展)” in pilot free trade zones, illustrate how Beijing balances technical control with narratives of openness and mutual benefit. The growing number of nations participating in PRC digital infrastructure projects suggests this approach has found receptive audiences, though the long-term implications for recipient countries’ digital sovereignty remain to be seen.

i-SOON Hacked Partner Countries, Focused on Telecoms, Ministries

The February 2024 leak of over 570 files from iS00N Information Technology revealed a sophisticated cyber operations program systematically targeting digital infrastructure in OBOR partner countries. These documents expose a meticulously engineered approach to cyber intelligence that goes far beyond traditional hacking, representing a comprehensive digital mapping of critical infrastructure along emerging economic corridors.

Table 1: iS00N Targets in OBOR Countries

| Region | Target Type | Notable Patterns |

| Vietnam | Government | Supreme People’s Court, Social Affairs Department. |

| Thailand | Government and Telecommunications | Multiple ministries (Foreign Affairs, Interior, Commerce), Senate, National Intelligence Agency, telecom operators (CAT, TOT, AIS). |

| Malaysia | Government and Military | Multiple ministries (Engineering, Interior, Foreign Affairs, Defense), military networks, DIGI telecoms. |

| Indonesia | Government | Foreign Affairs Ministry. |

| Cambodia | Government | Ministry of Economy. |

| Pakistan | Telecommunications and Government | Zong network, Punjab Counter-Terrorism Center email systems. |

| Kazakhstan | Telecommunications and Finance | Beeline, Kcell, Tele2, Telecom, Employee Pension Fund. |

| Kyrgyzstan | Telecommunications | Megacom operator. |

| Myanmar | Telecommunications and Government | MPT Communications (user data), government email systems. |

| Nepal | Government and Telecommunications | Nepal Telecom, government departments. |

| Philippines | Telecommunications | Bayan operator data. |

(Source: Document 01cdc26f-e773-4ad7-8808-d04abf16aae7.md)

The company’s operations reveal an extensive network of compromised systems across OBOR countries. According to iS00N’s internal documents, it has established monitoring capabilities targeting government ministries, telecommunications providers, and critical infrastructure (see Table 1). iS00N’s technical infrastructure includes Remote Access Trojans (RATs)—ShadowPad and ThreadStone—with multi-platform capabilities across Windows, Linux, Android, iOS, and MacOS systems, enabling comprehensive surveillance aligned with OBOR strategic priorities. [1]

In Southeast Asia, where maritime and land routes converge, iS00N has established substantial monitoring capabilities. For instance, it has accessed systems such as Thailand’s Ministry of Digital Economy and Society and Ministry of Interior, as well as Malaysia’s Ministry of Works. This likely has privileged it with visibility into infrastructure planning along the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor—a key component of OBOR (State Council Information Office, August 4, 2020). Beyond simple cyberattacks, iS00N has deployed four sophisticated tools to access target systems:

- Exploit and shellcode creation,

- Internet profiling and reconnaissance,

- Active attack capabilities, including webshell deployment, and

- Advanced document analysis and system debugging.

Central Asia, another important region for OBOR projects, has also been targeted by iS00N. In Kazakhstan, which is part of the New Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor, hackers have achieved persistent access to major telecommunications providers, including Beeline, Kcell, and Kazakhtelecom. Targeting telecommunications systems—a key tactic used by threat actors like iS00N—has taken place alongside access to financial institutions and regulatory bodies.

iS00N Part of New Digital Statecraft Paradigm

iS00N is part of a commercial ecosystem within the PRC that offers services that include sophisticated cyber capabilities previously limited to state actors (see Table 2 for service pricing). This market-driven approach has transformed cyber operations, likely making them more adaptable and better suited to precisely targeting critical digital infrastructure along OBOR corridors. Nevertheless, the state remains the key client for these services, and tasks are carefully aligned with state security objectives.

For Beijing, a key benefit of this approach is that it allows the government to maintain operational distance while simultaneously extending its digital reach. This strategic ambiguity provides valuable cover in multilateral fora such as ASEAN and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, where the PRC advocates for digital sovereignty for individual countries despite maintaining extensive monitoring capabilities through private proxies. This plausible deniability presents significant challenges for OBOR partner countries and the broader international community in confronting the PRC about its cyber operations.

Beijing has developed a complex ecosystem for implementing its digital strategy abroad, as the emergence of sophisticated cybersecurity contractors with deep ties to the Ministry of Public Security (公安部) indicates. While maintaining formal separation, these firms receive continuous strategic guidance that ensures their operations align precisely with national cybersecurity objectives. As internal training materials from iS00N show, there is extensive coordination between private contractors and the state security apparatus (China Brief, March 29).

Firms such as iS00N serve as critical intermediaries in the PRC’s digital expansion strategy and are examples of how the state has effectively privatized key aspects of its digital control infrastructure while maintaining strategic oversight. Contractors like iS00N operate with significant autonomy yet remain carefully aligned with broader national cybersecurity imperatives. This model potentially represents a new paradigm of digital statecraft, where the boundaries between private enterprise and state security become increasingly blurred.

Table 2: Pricing for iS00N’s Services

| Platform Category | Annual Cost in 1000s RMB (1000s USD) | Key Capabilities |

| Mailbox Platform | 600 (83) | Phishing, covert email collection |

| Twitter Platform | 400 (55) | Account hacking, monitoring |

| Windows RAT | 250–500 (35–69) | Stealth operations, remote management |

| Other OS RATs | 180–250 (25–35) | Cross-platform control |

(Source: Document 9fd06037-11f1-4ad5-9a7d-cbfb3fa4193b.md)

Implications for Digital Development

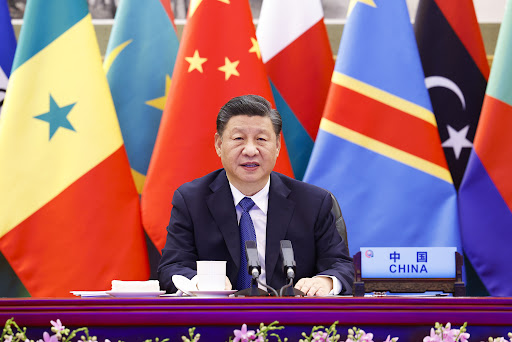

There are fundamental ttensions in the PRC’s vision of digital sovereignty. These are evident in Beijing’s recent multilateral commitments. At the latest BRICS [2] summit in Kazan, Russia, President Xi Jinping announced several new initiatives aimed at deepening digital cooperation. These included a China-BRICS Artificial Intelligence Development and Cooperation Center and a BRICS Digital Ecosystem Cooperation Network (MFA, October 23). Similarly, the Forum On China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Beijing Action Plan (2025–2027) unveiled at the September summit in Beijing outlined additional digital cooperation frameworks, such as the Action Plan for China-Africa Digital Cooperation and Development and strengthened cooperation in digital policy, infrastructure, and security (MFA, September 5; China Brief, September 20). These institutional mechanisms, presented as tools for “high-quality development,” contrast with the PRC’s extensive cyber activities targeting those same countries. These tensions are particularly striking in Africa, where the PRC has committed in its agreements at FOCAC to protecting users’ personal data and strengthening cybersecurity (MFA, September 5; CyberBRICS, October 22).

The PRC’s push in multilateral fora for digital sovereignty has gained momentum since 2015, when the first meeting of BRICS communications ministers in Moscow articulated priorities for information and communication technology (ICT) collaboration (Russian International Affairs Council, October 23). This momentum is reflected in Xi’s September 2024 FOCAC keynote address in Beijing, where he emphasized “digital cooperation (数字合作)” and announced plans to “build with Africa a digital technology cooperation center and initiate 20 digital demonstration projects” (PRC State Council, September 5).

The iS00N leaks make clear that the PRC’s promotion of digital sovereignty comes with the caveat that Beijing can maintain access to partner countries’ digital systems. While the PRC pushes “high-quality development” as part of its vision of digital expansion, the operational reality revealed through iS00N’s activities suggest that “high-quality development” serves as diplomatic cover for deepening digital control. The comprehensive targeting of both aligned and independent partners indicates that the PRC views surveillance capabilities as an essential component of its development strategy, even as it promotes digital sovereignty through multilateral forums.

Conclusion

The systematic deployment of private surveillance contractors along the Digital Silk Road reveals the PRC’s sophisticated approach to maintaining control while promoting digital sovereignty. Beijing’s emphasis on “high-quality development” frames digital cooperation as empowering partner nations, but the operational reality revealed in iS00N’s internal documents demonstrates that private firms serve as instruments for expanding the PRC’s cyber control in OBOR partner countries. The comprehensive targeting of both aligned partners and more independent nations suggests that the PRC views digital surveillance as an essential tool for maintaining strategic control over its technological investments.

The instrumentalization of private contractors represents an evolution in the PRC’s digital strategy. By maintaining operational distance through firms like iS00N while simultaneously championing digital sovereignty through UN frameworks and bilateral initiatives, Beijing has created an effective mechanism for extending its digital reach while preserving diplomatic credibility. The future of digital development along the Belt and Road will ultimately depend on whether recipient nations can effectively balance technological engagement with the PRC while protecting their digital sovereignty.

Notes

[1] Document 9fe6b262-9944-417d-a0c4-9f2de1de2994.md; document 12756724-394c-4576-b373-7c53f1abbd94.md

[2] BRICS refers to an informal intergovernmental organization of emerging market economies, which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates.