Tensions Rise Between Authorities and Muslims in Stavropol Region

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 196

By:

Soon after outlawing the Russian version of the Koran translated by the well-known scholar Elmir Kuliev (https://kavpolit.com/zapret-kulieva-ne-zapret-perevoda-a-zapret-korana/), it became apparent that the Russian authorities had opted for the most uncompromising plan to push back the onslaught of Islamization in the country. The process of Islamization, which spun out of government control after the fall of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s, has taken forms threatening to Moscow. Russian specialists were completely unprepared to deal with the proliferation of Islamic organizations. Regions that very few people associated with Islam 20 years ago became boisterous Muslim territories. Muftis’ boards have been established across the entire country, although in an uneven manner: indeed, even the most remote areas of Russia now have Muslim Spiritual Boards, such as Penza (https://muslime-penza.ru/), the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Region, Yugra (https://imanugra.ru/okrug/) and so on.

The Central Muslim Spiritual Board in Russia, which is based in Ufa (https://cdum.ru/), and its main competitor, the Council of Muftis of Russia, which is based in Moscow (https://www.muslim.ru/), do not recognize each other and are in fierce competition over mosques. Moreover, the North Caucasian Board of Muslims (a.k.a. the Coordination Council of Muftis of the North Caucasus) is supported by Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov and operates independently of the two national Muslim organizations (https://www.newsru.com/religy/18apr2012/expert.html). There is also the Russian Association of Islamic Accord (a.k.a. the All-Russian Mufti Board), but it is the youngest and the least effective group and includes everybody unhappy with the other Muslim organizations (https://www.rg.ru/2013/07/07/reg-skfo/rahimov-anons.html).

Given the diversity of these Muslim organizations, each one defines its public position on its own. Thus, the Russian Muslim organizations failed to issue a unified statement on the banning of the Koran translations in September (see EDM, October 3). They also failed to defend Russian imams under attack from the authorities (https://ria.ru/society/20131022/971794269.html).

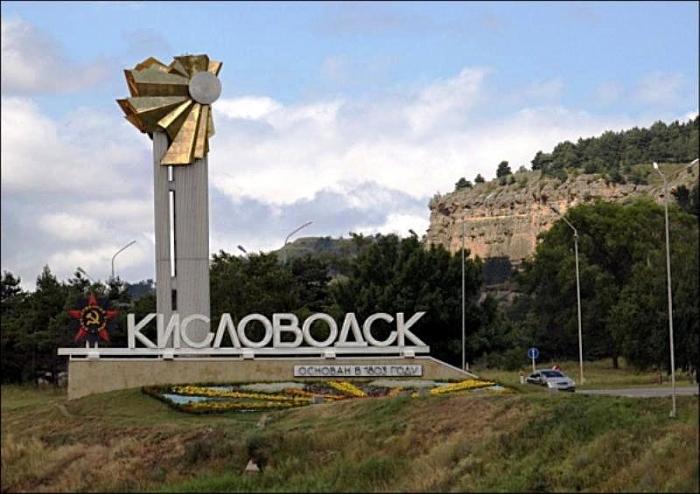

Kislovodsk is one of the most rapidly changing cities in Stavropol region in terms of the increase of the Muslim population, which has contributed to inter-religious tensions there in the past. In 2006, the imam of the city’s mosque was killed (https://www.finmarket.ru/news/529018/). Nonetheless, today, the city has a large population of ethnic Karachays, who have managed to build up their community despite official restrictions on settlement in the area that have been in place since the Soviet period. On June 5, 1964, the Council of Ministers of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the largest constituent republic of the former Soviet Union and the predecessor of contemporary Russia, imposed restrictions on settlement in the south of Stavropol region, in the area known as Kavkazskie Mineralnye Vody (Caucasian Mineral Waters). The decree was titled “On Restricting Registration of Citizens in the Resort Cities of Pyatigorsk, Kislovodsk, Zheleznovodsk, Yessentuki, Mineralnye Vody and the Adjacent Settlements of Stavropol Region” (https://www.ussrdoc.com/ussrdoc_communizm/usr_6093.htm). One of the reasons for imposing such restrictions was to stem the influx of people from the North Caucasus.

This fear among local Stavropol authorities of the growth of Muslim migrants from the rest of the North Caucasus has apparently not abated. On October 18, 2013, the imam of a Kislovodsk mosque, Kurman Baicharov, was arrested. The police claimed they found a package with a white substance that was preliminarily identified as illegal drugs (https://skfo.pro/news/3428). Baicharov now faces a sentence of up to 10 years in prison. Yet, the story appears to be murkier than officials are willing to admit. The police had been in conflict with Baicharov for a year because the mosque itself had been built without official permission. Even though the mosque was under construction right in the center of the city for four years, the authorities began criticizing the project only after it was completed, and the city administration pledged to demolish the building (https://kavpolit.com/o-snose-mechetej-v-kislovodske/). Such a move could spark mass unrest in the area. The authorities’ rationale for the arrest and imprisonment of one of the most unyielding imams is that it will be a powerful warning to other local Islamic clerics who try to establish small mosques in the city’s Muslim-populated areas. Stavropol region, of which Kislovodsk is a part, is undergoing an enormous demographic influx of North Caucasians who are moving to the area from neighboring North Caucasian republics (https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/migracionnye-processy-na-severnom-kavkaze-mezhnacionalnyy-aspekt). The Muslim migrants who have flocked to Kislovodsk initially set up mosques in private homes so as to not incite the apprehension of the local population. However, the growing Muslim residents of these areas of Stavropol expected eventually to be able to convince the authorities to officially recognize them as legally protected religious communities.

Overall, two mosques in Kislovodsk and another in neighboring Pyatigorsk are currently under threat of demolition (https://zlobnoe.info/kak-teper-dogovarivayutsya-o-mechetyax/). In the city of Stavropol, where local businessmen had also built a mosque without permission from the authorities, the Spiritual Board of the Muslims of Stavropol region has asked the government to refrain from demolishing the religious building (https://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/articles/228042/).

Stavropol is likely to experience fresh incidents of agitation against North Caucasians by Russian nationalists, who consider the area to be traditionally Cossack land. Such actions will probably be driven not so much by ethnic Russian residents of Stavropol as by external Russian activists from Krasnodar region or central Russia. But pitting radical Cossacks against the radical Muslim community of Stavropol region will be counterproductive on all accounts. The North Caucasians view these territories as their ancestral lands, taken away from them during the Russian-Caucasian War in the 19th century. The Cossacks, in turn, also regard this land as their own and do not want to share it with the North Caucasians.

Further adding to the area’s growing tensions, the Russian authorities recently picked the city of Pyatigorsk to be the new administrative seat for Alexander Khloponin, the Russian presidential envoy to the North Caucasus Federal District. The city was selected due to its strategic location in the central part of the region. However, this choice will inadvertently result in even more inter-ethnic conflicts due to an increased influx of people from the rest of the North Caucasus as regional political elites scramble to gather near Khloponin’s administration.

Thus, with its policy of prohibitions, Moscow is provoking the radicalization of the Muslim community of Russia, in particular in Stavropol region. This rise in tensions may result in an open confrontation in the near future.