Terrorist Attack in Kunming Reveals Complex Relationship with International Jihad

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 5

By:

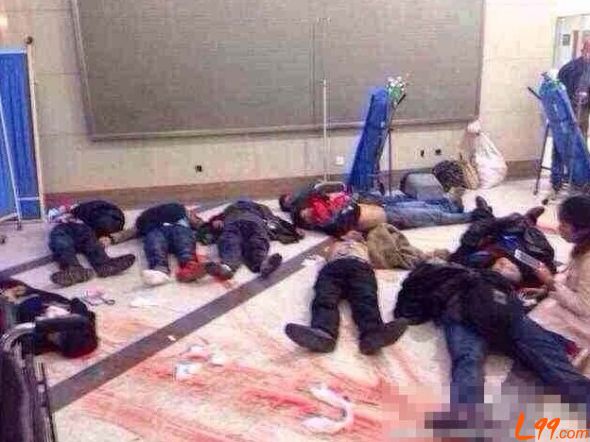

On March 1, at least six men and two women equipped with daggers stormed a train station in Kunming, the capital of China’s southwestern Yunnan Province, and murdered 29 people. Within two days of the attack, China released the photos and names of four suspects who the police killed during the attack, and four suspects who the police arrested in the post-attack search and investigation (South China Morning Post, March 3). All of the suspects were Uighurs from China’s Xinjiang Province, which confirmed suspicions that this “premeditated and organized” attack had political motives, including a combination of jihadism, separatism and revenge (Xinhua, March 2).

Awaiting TIP commendation

Most likely, the Pakistan-based and Uighur-led Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) will issue a statement commending this attack. The TIP’s leader, Abdullah Mansour, who seeks to become the “spokesman” for Uighurs in Xinjiang, often uses online jihadist forums to commend attacks, including those that Uighur militants carry out independent of the TIP in China (see Militant Leadership Monitor, Volume 5, Issue 2). For example, Mansour commended an attack in October 2013, when a Uighur family, including a husband (the driver), wife and mother, crashed a car into the main gate of Tiananmen Square in Beijing, killing several tourists and Chinese civilians, as well as the entire family, in the post-crash explosion (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cMzZA3g32oA , see also “Tiananmen Attack: Global, Local, or Both,” in China Brief, November 2, 2013).

Mansour also commended a “military operation” in Kashgar that he said “mujahidin of Turkistan” carried out against the “dogs of the Chinese government” on April 2013 (SITE Monitoring, January 15). In that attack, 21 people were killed in a fight after a government community patrol uncovered a group of Uighurs making explosives (China Daily, April 30, 2013). In both the Tiananmen Square and April 2013 Kashgar attacks, Mansour did not claim TIP participation, but in other attacks, the TIP has shown evidence of its involvement. In an attack in Kashgar in July 2011, for example, Uighur militants rammed trucks into Chinese police marching on a street and stabbed to death nearly 20 officers. Weeks later, the TIP showed videos of TIP fighters involved in the attack training in a mountainous area (presumably Pakistan) and the flyers that the Chinese police released of these TIP militants before the militants were “martyred” when the police tracked them down on the outskirts of Kashgar (Times of India, September 8, 2011).

If the TIP is able to inspire Uighurs in Xinjiang to—in the words of the TIP—“use weapons and not words” to fight for an independent “East Turkistan,” which is the name Uighur separatists use to refer to Xinjiang, it would be a victory for the militant group (Tourism of the Believers 7, May 7, 2013). The attack in Kunming may be an example of Uighur militants with local grievances following the TIP model, if not orders from Mansour or other Pakistan-based militants. The Chinese security forces showed evidence after the attacks that the attackers in Kunming displayed a black flag like the one used by al-Qaeda with the Islamic shahida (testimony of faith), but that also bore the Islamic crescent and star symbol of “East Turkistan.” This suggests both religious and nationalistic inspiration, reflecting the influence of the TIP, which also uses al-Qaeda’s flag, and separatist sentiments.

Motivations and New Tactics

While the TIP and international jihadist ideology may have played a role in inspiring this attack, the attackers may also have had revenge foremost in their minds. In September 2013, up to 100 Uighurs were reportedly arrested on the border between Yunnan Province (whose capital in Kunming) and Laos (Radio Free Asia, October 3, 2013) They may have been fleeing to Laos after a June 2013 incident in Hotan, in which several dozen Uighurs were killed during a fight between police and locals after the police broke up a sermon at a mosque and arrested the imam. This led to large protests in the town’s main square and the killing of several Chinese police officers with daggers (Radio Free Asia, June 30, 2013).

Nonetheless, the targeting of a public location such as a train station is a new tactic in Uighur militancy in China. Previous attacks in Xinjiang involved ramming cars and stabbings of civilians in pedestrian restaurants and streets, but never major transportation hubs (sina.com, August 16, 2011). This attack in Kunming also featured women among attackers, which is common with militants in the North Caucasus but not in Xinjiang. Similarly, the targeting of a train station may suggest influence from abroad, such as the Caucasus, where militants frequently target Russian transportation hubs, such as the “black widows” who attacked the train station and a trolley car in Volgograd in the run-up to the Sochi Olympics (smh.com.au, January 22).

Even if the militants were acting in revenge for arrests at the border with Laos, it appears they still were part of a broader network of Uighur militants in Xinjiang. The use of daggers to carry out mass stabbings in the Kunming train stations is an attack style that has occurred several times in 2013. The most infamous incident occurred in Turpan, near Urumqi, on June 26, 2013, when more than 40 people were killed when a group of about 15 Uighurs attacked a police station with daggers and petrol bombs (China Daily, July 8, 2013). The attack in Kunming therefore was consistent with the Turpan attack and other incidents and may have been influenced or organized by the same network in other dagger attacks.

An Attack of Opportunity or Organization?

An attack in Kunming is distinct because it is one of the few examples of Uighur militancy taking place outside of Xinjiang. However, if the militants were connected to the Uighurs who were arrested at the border between Yunnan and Laos, this may have been an attack of opportunity more than an attempt to strike “inner China.” Kunming is the closest major city to Yunnan’s border with Laos, and the train station is a convenient target because it is located near the district of Kunming that hosts Kunming’s Uighur community (Muslims, including Uighurs and other ethnic groups, comprise about 10% of Yunnan’s overall population).

At the same time, the attack in Kunming and the attack in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in October 2013 suggest that there may be an organized plan among Uighur militants to strike eastern China’s majority ethnic Han areas, which, unlike remote Xinjiang, gain the attention of the whole country in China. In an April 2012 video, a Turkish TIP fighter issued a video statement presaging attacks in eastern China, while also showing the TIP’s international agenda. The militant, named Nururddin, was “martyred” in 2013 in a suicide attack on U.S. forces in Afghanistan. Nuruddin said in the video, which was titled “Advice to Our Muslim Brothers in East Turkistan,” that “Islamist flags will soon be raised at the White House and Beijing’s Tiananmen Square” (Ansar al-Mujahidin Network, October 17, 2012).

Conclusions

The attack in Kunming is symptomatic of new trends in Uighur militancy. Like the Tiananmen Square attack and this Kunming attack, Uighur militants may be inspired to carry out future attacks in eastern China, especially at symbolic sites like Tiananmen Sqaure or sites that attract large gatherings of people, such as transportation hubs. Due to the difficulty of obtaining guns in China, the weapons of choice for such militants will likely continue to be daggers, Molotov cocktails and vehicles that can be used to ram into civilians or police. Because China will likely implement heightened security and intelligence gathering in Xinjiang and Uighur communities in eastern China, future militant cells may seek to employ women or even foreigners from other Muslim countries to carry out attacks, who will likely be under less scrutiny than Uighur men from Xinjiang.

In addition, future attacks, like this one in Kunming, may be impossible to label strictly as a “global jihadist” attack or a “locally rooted” attack. Most attacks will feature tactics, symbolism and propaganda with influence from abroad even while many militants have local motivations and grievances. However, if Uighur militants in Xinjiang hope to shift from sporadic violence that exists now into a consistent insurgent movement, they will need to deepen their contacts beyond China’s borders. They could reach into Pakistan, where groups like the TIP and other Central Asian militant groups are active and can provide Uighur militants with greater access to international funding streams. Abu Zar al-Burmi the spiritual leader of one such group, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), promised the TIP that China will replace the U.S. as the “number one enemy” (To the Muslims of Turkist?n: We Have To Prove Islam Is In Our Hearts, Islam Awazi, July 10, 2013). In addition, Uighur militants from Xinjiang may be able to seek funding from sympathetic Muslim or diaspora Uighur populations in Kyrgyzstan and take advantage of lightly governed spaces in that country for training.

The ultimately victory for the Uighur militants would be if China internalizes this attack as its own “9/11”—as some China media have done—and reacts to the militant crisis in a disproportionate way that generates more recruits for the militants and validates the propaganda claims of militants that the Uighurs are suffering oppression. Therefore, any Chinese security forces operations into Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan or other countries or investigations of suspects within Uighur communities must be taken with great precision, coordination and sensitivity to sources of potential backlash.