The Cost to Ukraine of Crimea’s Annexation

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 70

By:

The Ukrainian government has apparently understated its possible economic losses caused by Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula. According to a recent valuation by the Ukrainian Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Russia seized an estimated 127 billion hryvna ($10 billion) of assets in Crimea, which included both natural resources and business assets (https://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2014/04/7/7021631/).

Calculating Crimea’s value in economic terms is a complex exercise. But even rough estimates suggest the true figure exceeds the government’s estimate by several times. The most lucrative businesses and reserves taken over by Russia appear to be those in the natural gas and oil sector located out in the Black Sea (for a discussion of the Crimean annexation’s impact on Black Sea maritime boundaries see EDM, March 21). Currently, some of these reserves are being operated by Chornomornaftogaz, which was declared “nationalized” by the Crimean authorities (Interfax-Ukraine, March 14). The company operates four gas deposits on the Black Sea shelf and three deposits onshore in the Crimean peninsula. Chornomornaftogaz is also drilling for oil near Shchelkino in small quantities of less than 30,000 tons per year. In 2013, Chornomornaftogaz’s output was 1.6 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas, and it aimed to double production by 2015 (https://chernomorneftegaz.com/index.php/ru/investoram). The company’s value could thus be estimated at a figure close to $1 billion based on its projected output over the time span of 15 years.

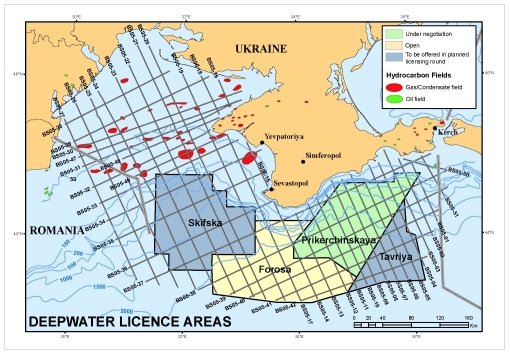

In addition to the resources being exploited by Chornomornaftogaz, Ukraine lost several other abundant gas and oil fields that the Ukrainian government had offered up for Production Sharing Agreement (PSA)–type concessions. In contrast with the relatively low value-loss estimates of the environment ministry, Ukrainian Energy Minister Yuriy Prodan declared, “we lost important fields in the Black Sea shelf. We evaluate this loss at $40 billion, in terms of lost income from shale gas from Crimea” (ITAR-TASS, April 11).

But even this figure is most likely understated. In fact, $40 billion may refer just to the value of the Prykerchenske natural gas and oil deposit allocated for use by the company Vanco Prykerchenska. The deposit includes an estimated 180 bcm in deep-water natural gas reserves as well as 83 million tons of oil. According to the project’s PSA, Ukraine was supposed to own 70 percent of the cash flows associated with the Prykerchenske field. Using projected prices of natural gas costing $300 per thousand cubic meters and oil at $100 per barrel, while also assuming 50-percent investment and capital expenditure deductions, the value of these reserves could be perhaps roughly estimated at $40 billion. Notably, DTEK—a company owned by Ukraine’s richest businessman, Rinat Akhmetov—has a stake in Vanco Prykerchenska via its subsidiary DTEK Oil and Gas (https://www.dtek.com/en/our-operations/associated-companies/vanco#.U0hDovl_scE). Previously, Vanco Prykerchenska’s US Partner, Van Dyke Energy Company, sold a controlling interest in Vanco Exploration to Russian Lukoil, but retaining a substantial stake (https://www.vandyke-energy.com/oil-and-gas-operations, accessed April 11, 2013). Vanco Prykerchenska is still formally a party to the PSA entered in 2006 with Ukrainian authorities, later revoked by Yulia Tymosheko’s government in 2008 and reinstated under then-president Yanukovych’s administration in February 2014 (https://forbes.ua/news/1347492-kabmin-vozobnovil-soglashenie-s-vanco).

Another important PSA—regarding the Skifske deep-water natural gas deposit—was negotiated by the Ukrainian government with a consortium led by ExxonMobil. The consortium also included Royal Dutch Shell and Romania’s OMV Petrom. With an investment outlay of some $12 billion, the project could unfold to extract output from 200 bcm of natural gas reserves over 50 years. The value of these reserves could be as high as $30 billion or even higher. For now, ExxonMobil has put its offshore activities in Ukraine on hold (Reuters, March 7), and the company is dependent on Russia because of its participation in a larger natural gas project with Russian Rosneft in the Arctic. ExxonMobil risks losing this opportunity if it refuses to work with Gazprom on exploiting the Skifske field.

Other estimated natural gas resources, including newly-discovered methane hydrates in the Black Sea, amount to 1.5 trillion cubic meters. While the oil resources are around 1 billion tons. Overall, the deep-water gas reserves that are supposed to legally belong to Ukraine are estimated at 4–13 trillion cubic meters, according to Ukrainian government data (https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/Energy-Voices/2014/0321/With-Crimea-annexation-Putin-expands-oil-and-gas-empire).

Apart from oil and gas, Crimea offers some of the highest potential in Ukraine to build and operate solar power stations (https://invest-crimea.gov.ua/news_body.php?news_id=381). Crimean natural resource reserves also include 1.4 million hectares of land owned by the Ukrainian government (https://invest-crimea.gov.ua/, accessed April 13). The estimated value of this land, assuming a price of $700 per hectare, could be around $1 billion. A valuation of natural reserves that promote Crimea’s tourism potential as well as state-owned tourism facilities on the peninsula could also technically be undertaken.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea also means a significant loss of transportation sector infrastructure for Ukraine. Notably, Simferopol International Airport is the third busiest in Ukraine, having serviced 1.2 million passengers in 2013 (https://www.sobytiya.info/news/14/38229). The network of Crimean motor roads is also in relatively good condition. Moreover, the transportation sector includes airspace routes leased to international airlines flying over Crimea. The overflight fees they had to pay to the Ukrainian aviation authorities may now be lost.

Finally, in the maritime sector, a passenger sea port in Yalta provides high tourism potential to Ukraine. Whereas, cargo ports in Kerch, Feodosiya and Yevpatoriya reflect significant losses in Ukraine’s international trade potential. Additionally, Kyiv is losing possible substantial cargo port facilities in Sevastopol where the company Avlita—part of Rinat Akhmetov’s SCM holding—had plans to expand the seaport to service about 8 million tons of commodities cargo per year (https://www.avlita.com/upk/rule). It should be noted that, until now, the state-owned ports in Crimea were mostly controlled by Ukrainian oligarchs, including former president Yanukovych’s son Oleksandr (https://www.theinsider.ua/rus/business/524edefdbc67e/).

Clearly, the Ukrainian government will need to develop a restitution strategy to re-claim the ownership of its lucrative Crimean assets from Russia by taking its case before international courts. Such an approach, and its associated prolonged legal process, would also serve to increase the costs to Russia for “owning” Crimea and possibly deter Moscow from further intrusion into southeastern Ukraine. But there is a risk that the Ukrainian government, which is currently operating in “emergency” mode, might not find the resources to pursue such an expensive, drawn-out legal strategy.