The Hadramawt: AQAP and the Battle for Yemen’s Wealthiest Governorate

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 14

By:

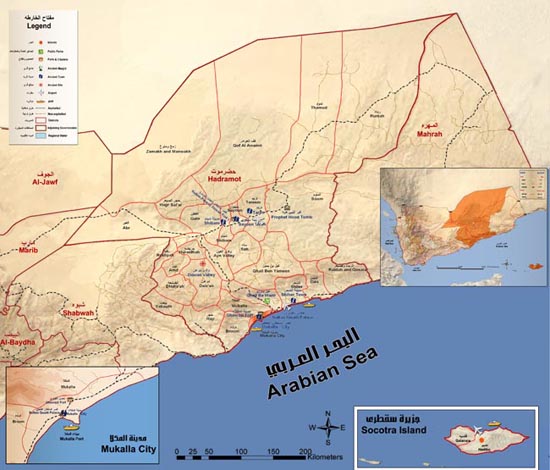

More than three months of intense aerial bombardment by Saudi Arabia and its coalition partners have left much of Yemen in ruins. Few places in the country are not experiencing the effects of the air campaign, civil war and the deprivations caused by the coalition’s blockade of Yemen’s ports. Yemen’s eastern Hadramawt governorate is a notable exception.

Since the beginning of the Saudi-led “Operation Decisive Storm” on March 25, the Hadramawt has remained relatively stable despite the fact that much of the governorate is controlled by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). While AQAP’s leadership has been targeted by U.S. drone strikes, the organization has not been targeted by the Saudi-led coalition which has focused its efforts on bombing the Houthis, Yemen’s northern-based Zaydi Shi’a rebels, and their allies. The Hadramawt has also remained well provisioned because supplies are still transiting its ports, in particular the port city of Mukalla, which is under the nominal control of AQAP (Yemen Times, May 29). The relative stability of the Hadramawt has attracted thousands and quite possibly tens of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) who are fleeing the aerial bombardment and civil war that has engulfed most of Yemen.

Set among well-watered canyons, deserts and towering mountains, the Hadramawt is Yemen’s largest governorate. It is also its wealthiest in terms of natural resources. Most of Yemen’s remaining gas and oil reserves are located here. For instance, a single block, Block 19, located within the Say’un-Masila Basin, accounted for more than 32 percent of Yemen’s oil production before most of the country’s oil and gas exports went offline following the Saudi-led intervention.

Control of the Hadramawt and its natural resources is critical to any future government of a unified Yemen. The relative stability of the Hadramawt is, however, unlikely to last as AQAP, the Islamic State, Saudi Arabia and forces aligned with the Houthis battle for control of what is one of Yemen’s most strategically and economically important governorates.

From AQAP to the ‘Sons of the Hadramawt’

Before the start of Saudi-led operations against the Houthis and their allies, AQAP—while still a formidable organization—was on the defensive in much of Yemen. The Houthis, whose membership is predominately Zaydi Shi’a, are the sworn enemies of AQAP. In turn, AQAP and Salafists generally view the Shi’a as heretics. The Houthis and members of various militant Salafist organizations, like AQAP, have additionally been locked in an ongoing war for much of the last decade. With the Houthis’ rapid rise to power in 2014 and 2015, the Houthis had pushed AQAP out of key governorates that included al-Jawf, in northern Yemen, and al-Bayda, in central Yemen.

Since the start of the Saudi-led airstrikes on the Houthis and their allies, AQAP is resurgent and now enjoys a degree of operational freedom that it has not had since the 2011-2012 popular uprisings. The Houthis and the forces allied with them, including some of Yemen’s Republican Guard, shifted their strategic focus from attacking militant Salafist-aligned forces like AQAP, to securing positions in southern Yemen, namely in Aden. At the same time, the Houthis’ and their allies’ ability to move men and materiel around the country has been impeded by the Saudi-led airstrikes. As a result, AQAP went on the offensive.

On April 2, AQAP attacked a prison in Mukalla and freed more than 300 prisoners, some of whom were senior AQAP operatives, including Khalid Batarfi who had been a regional commander for AQAP and played a key role in AQAP’s 2011-2012 takeover of Abyan (al-Jazeera, April 2). In the days following the April 2 prison break, AQAP rapidly consolidated its hold on Mukalla, Yemen’s fifth-largest city and the capital of Hadramawt governorate. The elements of the Yemeni Army that were charged with defending the city either fled from their posts or switched sides. AQAP also looted the Mukalla branch of the Central Bank of Yemen, as well as army warehouses and supply depots (Yemen Times, April 6). By April 16, AQAP, with the help of local allies, had seized the nearby Dhaba Oil Terminal at Ash-Shihr and al-Riyan Airport and had routed the Air Defense 190 Brigade and the 27th Mechanized Infantry Brigade (The National, April 18).

Since taking control of Mukalla and the other parts of the Hadramawt that it now controls, AQAP has pursued an accommodative policy. Following their rapid takeover of Mukalla, AQAP’s regional leadership, now headed by the recent escapee Batarfi, has worked to build a governing coalition with local authorities and the Hadramawt National Council (HNC). The HNC is an offshoot of Hadrami Tribal Confederation (HTC), which initially opposed AQAP’s takeover of Mukalla. The HNC’s core membership is made up of Salafists, many of whom have close ties with Saudi Arabia. The HNC and AQAP are seemingly united by the fact that they view the Houthis as a common enemy. While AQAP and its forces remain in control of security and military operations in Mukalla and other areas in the Hadramawt that they control, day to day governance is being left to local bureaucrats under the supervision of the HNC.

AQAP’s shift in strategy in the Hadramawt is also illustrated by the fact that they are now calling themselves “Sons of the Hadramawt.” Taking up a new name in order to emphasize a shift in strategy is nothing new for AQAP. By calling themselves by this name, AQAP is indicating that they are deeply embedded in the political, tribal and religious milieus of the Hadramawt. [1] Thus far, AQAP has not moved to impose its version of Shari’a on the inhabitants of those areas that it controls. However, AQAP has instituted an unpopular ban on qat, the mild narcotic used by a majority of Yemeni men (al-Bawaba News, May 15).

Despite its ban on qat, which is only sporadically enforced, AQAP’s accommodative policy in the Hadramawt seems to be bearing fruit for the organization. The Hadramawt, and in particular the city of Mukalla, are relatively stable, and the governorate is attracting thousands of IDPs seeking shelter and aid. In a little more than three months, AQAP has also replenished its funds, gained access to a wide range of medium and heavy weaponry and undoubtedly has access to hundreds, if not thousands, of new recruits in the form of IDPs, many of whom will be attracted by the nominal salaries offered by AQAP. The only current threats to AQAP are the Islamic State and what remains of the Yemeni Armed Forces in the northern reaches of the Hadramawt.

A Delicate Balance

While AQAP operates throughout the Hadramawt, it, however, effectively controls only Mukalla and the southernmost valleys of the governorate. The northern sections of the governorate, including the city of Say’un, are under the nominal control of Major General Abdul Rahman al-Halili, the commander of Yemen’s First Military District, the country’s largest. [2] Al-Halili commands five brigades. However, it is doubtful that any of the five brigades are at full strength.

In a recent interview, Major General al-Halili claimed that he was a supporter of exiled Yemeni President Abd Rabbu Mansur Hadi (Middle East Eye, June 27). However, al-Halili, who was most recently the commander of the 3rd Armored Brigade, a part of the Republican Guard, is far more likely to be aligned with former Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh. While al-Halili was the commander of the 3rd Armored Brigade, he, along with many other commanding officers within the Republican Guard, was reluctant to take orders from President Hadi. Al-Halili was promoted by Hadi and given command of the First Military District as part of a reshuffling and dispersal of field grade and general officers within the Republican Guard (SABA, July 12, 2014). Given his history, it is doubtful that al-Halili is in fact a supporter of Hadi or his exiled government. In late April, a plan to make the city of Say’un, the headquarters of the First Military District, a temporary capital for Hadi and his government was proposed. The proposal went nowhere. Whether this was due to insecurity or a lack of support from al-Halili remains an open question.

Regardless of al-Halili’s loyalties, he has thus far kept his forces intact and largely de-politicized. This has allowed him to maintain a delicate balance within the parts of Yemen that he controls. His forces have acted as an effective bulwark against both AQAP and the Islamic State. While al-Halili’s forces actively patrol the areas under their control, they do not target AQAP in the areas that the militants control. Al-Halili’s strategy is to let AQAP and the Islamic State fight one another while he conserves his resources for whatever might come next.

AQAP also has to contend with the operations of Islamic State in the Hadramawt. While Islamic State operatives have been present in Yemen for close to a year, the group began operations with a suicide attack on two mosques in Sana’a on March 20 (al-Bawaba News, March 20). Since that attack, the Islamic State has carried out additional attacks on mosques in Sana’a and has also targeted Yemeni soldiers. The Islamic State has benefited from a number of defections from AQAP, including Jalal Baleidi, who is now a senior commander within the former group’s “Wilayat Hadramawt,” or Hadramawt Province. The Islamic State’s presence in Yemen remains relatively limited. However, the organization is expanding and is a threat to AQAP’s dominance as the premier militant Salafist organization in Yemen. Much of the fighting between AQAP and the Islamic State has taken place within the Hadramawt. Both organizations undoubtedly recognize the strategic and material benefits of controlling parts or all of the governorate. Islamic State operatives maintain a presence in the Wadi al-Hajr, just west of Mukalla. AQAP and allied tribal forces have mounted attacks on Islamic State forces in the area, but have thus far been unable to defeat them. The Islamic State launched its first attack in the Hadramawt on April 30, when it attacked a military checkpoint and a government building in Tarim in the north of the Hadramawt (al-Arabiya, April 30). The Islamic State beheaded three of the captured soldiers. Since that attack, the Islamic State has focused its efforts on targets associated with the Houthis in Sana’a and on AQAP itself.

A Long Sought Prize

AQAP and the Islamic State are not alone in viewing the Hadramawt as a prize territory. Saudi Arabia has a long and abiding interest in the governorate. Many of Saudi Arabia’s wealthiest families, like the Bin Ladens, hail from the Hadramawt. In 1809, followers of the Wahhabi sect, now the state-sanctioned sect of Saudi Arabia, invaded and occupied the Hadramawt. During the occupation, the Wahhabis destroyed Islamic shrines as well as libraries.

While conservative, the Islamic traditions that have predominated in the Hadramawt have generally been moderate and influenced by various Sufi traditions. However, beginning in the early 1980’s, Saudi Arabia, much as it did across the Muslim world, began funding a host of Salafist and Wahhabi-inspired imams, mosques and religious centers in the Hadramawt. [3] As a result, over the next three decades, the religious landscape of the Hadramawt changed dramatically as the far more radical Salafist and Wahhabi-influenced interpretations of Islam took hold. This changing religious landscape has reinforced the Hadramawt’s links with Saudi Arabia.

However, Saudi Arabia’s interest in the Hadramawt extends well beyond religious proselytism and protecting the interests of wealthy families like the Bin Ladens. The Kingdom’s primary interest in the governorate is the possible construction of an oil pipeline. Such a pipeline has long been a dream of the government of Saudi Arabia (Wikileaks, June 6, 2008; Yemen Times, April 9, 2012). [4] A pipeline through the Hadramawt would give Saudi Arabia and its Gulf State allies direct access to the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean; it would allow them to bypass the Strait of Hormuz, a strategic chokepoint that could be, at least temporarily, blocked by Iran in a future conflict.

The prospect of securing a route for a future pipeline through the Hadramawt likely figures in Saudi Arabia’s broader long-term strategy in Yemen. However, in the short-term, Saudi Arabia probably views AQAP’s control of the southern Hadramawt as being advantageous to its current war against the Houthis. So far, Saudi Arabia and its allies have not targeted AQAP or the Islamic State in the Hadramawt or elsewhere in Yemen. In the case of the Hadramawt, it is probable that Saudi Arabia sees the new comparatively “moderate” AQAP as a potential ally in its war against the Houthis and as a check on the Islamic State. This would mirror the situation in Syria where al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra has for some time been regarded by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States as a relatively moderate proxy force that serves the dual purpose of fighting the Shi’a-dominated government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and acting as a check on the Islamic State’s growing power in the region.

Outlook

All parties involved in the current conflict, including AQAP and the Islamic State, are keenly aware of the strategic and material importance of the Hadramawt. The natural resources in the Hadramawt are critical to the economy of a unified Yemen. Its extensive coastline, its ports and oil handling infrastructure and its border with Saudi Arabia mean that the Hadramawt is a strategic prize for whatever group that can control the governorate—either directly or via a proxy force. While much of the governorate is presently relatively stable when compared with other parts of Yemen, this stability is unlikely to last.

In the short-term, AQAP will remain in control of Mukalla and large parts of southern Hadramawt. AQAP’s accommodative policy and its renewed efforts to coopt local tribes and power structures in the Hadramawt will strengthen the organization’s hold on the territorial gains that it has made. This, combined with the fact that AQAP’s two primary opponents in the region—the Houthis and Saleh-loyalists—have largely been neutralized, will ensure AQAP’s continued growth in the Hadramawt and in large swaths of southern Yemen. AQAP may also benefit from the fact that it could well be regarded as a useful proxy by Saudi Arabia in its war against the Houthis. Saudi Arabia and its allies are arming a host of disparate militias across southern Yemen. It is almost certain that some, if not much, of the funding and materiel will make its way to AQAP and quite possibly the Islamic State.

While the Islamic State’s current focus seems to be on attacking targets associated with the Houthis in Sana’a, given the importance of the Hadramawt, the group will also continue to battle AQAP to maintain its foothold in the region as well. The internecine struggle between AQAP and the Islamic State may spread beyond Wadi al-Hajr to other parts of the Hadramawt. The fight between the two jihadist groups is likely to be the only short-term check on the growth of both organizations, not only in the Hadramawt, but also in Yemen. Apart from Major General al-Halili’s forces in northern Hadramawt, most of the Yemeni Army is divided and locked in a battle that pits the Houthis and allied forces against southern separatists and Islah, the Yemeni branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. Al-Halili’s forces do not have the capability to go on the offensive against AQAP or the Islamic State without additional aid, which neither the Yemeni government in exile nor Saudi Arabia have provided. Allowing AQAP and the Islamic State to gain and—in the case of AQAP—maintain a presence in the Hadramawt all but ensures the long-term instability of not only the governorate but also of Yemen as a whole. If and when a unity government is formed in Sana’a, it and what remains of the Yemeni Armed Forces, will then face the challenge of not only reconstructing Yemen, but also the Sisyphean task of removing AQAP and the Islamic State from the Hadramawt.

Michael Horton is an analyst whose work primarily focuses on Yemen and the Horn of Africa.

Notes

1. AQAP is not the first organization to use the name. The original “Sons of the Hadramawt” organization was one whose members supported the secession of the Hadramawt from Yemen. Other members of the organization wanted the Hadramawt to become part of Saudi Arabia.

2. The First Military District encompasses much of the Hadramawt and the neighboring governorate of al-Mahra, which borders both Saudi Arabia and Oman.

3. For background see: Charles Allen, God’s Terrorists: The Wahhabi Cult and the Hidden Roots of Modern Jihad, Da Capo Press, 2009.

4. See: https://www.gulfinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Threats_to_the_Saudi_Oil_Infrastructure.pdf.