The Haqqani Network and Cross-Border Terrorism in Afghanistan

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 6

By:

There has been an increase recently in alleged missile strikes inside Pakistani territory by U.S. forces operating across the border in Afghanistan. The attacks come at a time when there is a growing call in the United States for strikes on Pakistani territory to take out al-Qaeda safe havens believed to exist in the tribal agencies along the Afghan border. NATO military commanders in Kabul have time and again expressed their dissatisfaction with the performance of Pakistani security agencies in stopping the infiltration of armed Taliban groups like the “Haqqani Network” from Pakistan’s tribal areas into Afghanistan. Despite the fact that U.S. authorities have consistently expressed their respect for Pakistan’s sovereignty, they are simultaneously growing impatient with the growing strength of the militants on the Pakistani side of the border. According to U.S. officials, the cross-border activities of these militants have a direct impact on U.S. operations in Afghanistan.

Attack on Lwara Mundi

A March 12 missile attack targeted a home in the town of Lwara Mundi in North Waziristan, killing two women and two children. Pakistan quickly registered a protest with the Coalition forces in Afghanistan, deploring what an official called “the killing of innocent people.” However, U.S.-led Coalition officials in Kabul said that the target of the precision-guided missile was a safe house of the Haqqani Network based in the border region of the North Waziristan agency (Daily Nation [Lahore], March 14). Just a day after Pakistan lodged its protest over the attack in Lwara Mundi, another missile attack on March 16 left as many as 20 killed, including a number of foreign fighters, when a house was targeted in Shahnawaz Kheil Doog village near Wana, the regional headquarters of South Waziristan. It is believed that the missiles were fired from two U.S. unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in the belief that the house was being used as a training camp for terrorists (Daily Post [Lahore], March 14). Though a U.S. Central Command spokesman would only say the missiles were not fired by any military aircraft—Predator UAVs are operated by the CIA—U.S. forces took responsibility for the earlier “precision-guided ammunition strike” on Lwara Mundi but made it clear that the target was the Haqqani Network (Daily Mail [Islamabad], March 14; AFP, March 13; Reuters, March 17). A spokesman for Coalition forces in Afghanistan said that Pakistan was informed after the attack, not before. The spokesman made it clear that U.S. forces will respond in the future as well if they identify a threat from across the border in Pakistan’s tribal belt (Daily Times [Lahore], March 14). Though the Pakistani tribal region has been a center of concern since late 2001 when hundreds of al-Qaeda fighters took refuge there, the lawless belt between Pakistan and Afghanistan is now receiving attention for the growing activities of the Haqqani Network, a Taliban group which has been spearheading the insurgency against U.S.-led NATO forces in Afghanistan.

A Profile of the Haqqani Network

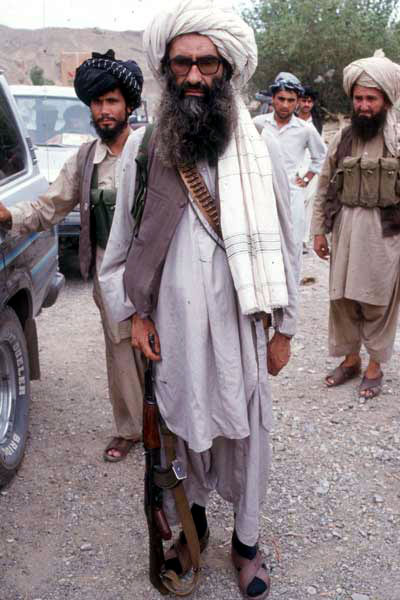

The “Haqqani Network” is a group of militants led by Jalaluddin Haqqani and his son, Sirajuddin Haqqani. Jalaluddin, who is said to be in his late 70s, is a noted Taliban commander with a bounty on his head and a place on the U.S. most-wanted list. Jalaluddin Haqqani is considered to be the closest aide of Taliban supreme leader Mullah Omar and was a noted mujahideen commander in the 1980s resistance against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan. He rose to prominence after playing a leading role in the defeat of Muhammad Najibullah’s communist forces in Khost in March 1991. After the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in 1995, the senior Haqqani joined the Taliban movement and rose to the top echelon of power in the regime. He remained a minister during the Taliban government and a top consultant to Mullah Omar. The senior Haqqani has rarely been seen in public since the collapse of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in late 2001, when he is believed to have crossed into Pakistan’s Waziristan Tribal Agency to evade the advance of Coalition forces. There are continuous rumors that he is seriously ill or has even died. However, his son, Sirajuddin Haqqani, alias Khalifa, has not only filled the void created by the absence of his veteran jihadi father, but his well-organized group, known as the Haqqani Network, has emerged as the most dangerous and challenging foe for the Coalition forces in Afghanistan.

The Haqqani Network is based in the Dande Darpa Khel village near Miramshah, headquarters of the North Waziristan Tribal Agency. The town is about 10 miles from the Afghan border. Sirajuddin, believed to be in his early thirties, has a $200,000 bounty on his head. He belongs to the Zadran tribe of Afghanistan, which also has roots on the Pakistani side of the border. Residents in Dande Darpa Khel say that the junior Haqqani grew up in this small and remote town of North Waziristan, once the operational headquarters of his father’s jihadist activities. It is said that he attended the now defunct religious seminary which his father founded in the early 1980s in the town of Bande Darpa Khel. Though he could not be considered a religious scholar, Sirajuddin certainly sharpened his jihad skills under the guidance of his father. Considered to be the leader of a new generation of Taliban militants on both sides of the border and a bridge between the Pakistani and Afghan Taliban, NATO officials have recently declared him as one of the most dangerous Taliban commanders in the ongoing insurgency in Afghanistan (Los Angeles Times, March 14). He is suspected as the mastermind behind the deadly attack on Kabul’s only five-star hotel last January, which left eight people killed, including three foreigners (Daily Times, March 4). A U.S. military spokesman at Bagram Air Base described Sirajuddin’s role in a series of devastating suicide bombings: “We believe him to be much more brutal and much more interested in attacking and killing civilians. He has no regard for human life, even those of his Afghan compatriots” (AP, February 21). The United States has offered a $200,000 bounty for Sirajuddin, who is expanding his operations from east Afghanistan into the central and southern regions.

Sirajuddin has evaded capture several times despite attempts by Pakistani security forces to arrest him at his house and seminary in Miramshah in North Waziristan. In 2005 Pakistani officials raided his headquarters in Dande Darpa Khel, the religious seminary and residential compound used by his network. The raiding party seized huge caches of weapons and ammunitions but Sirajuddin again escaped arrest (Dawn [Karachi], September 15, 2005).

Sirajuddin is also reported to have taken credit for a suicide-truck bombing in Khost on March 3 that killed two NATO soldiers and two Afghan civilians (Xinhua, March 13). The attack on a government building involved a truck loaded with explosives, drums of petrol, mines and gas cylinders. A Taliban videotape of the bombing was released on March 20, including a statement from the German-born suicide bomber, Cuneyt Ciftci—also known as Saad Abu Furkan—“The time has arrived to give sacrifices to Islam. Since we lack resources to fight the enemy, we will have to turn our bodies into bombs” (Newkerala.com, March 20).

On the Pakistani side of the border, Sirajuddin’s influence has been growing as a “revered jihadist commander.” He strongly opposed Maulvi Nazir’s campaign against Uzbek and other foreign militants waged earlier this year by the militant tribal leader in South Waziristan (see Terrorism Monitor, January 11). He is reported to have played an important role in stopping the fighting between Maulvi Nazir’s tribal militia and Uzbek militants in Wana and the surrounding area in March last year. Sirajuddin took part in a tribal jirga, attempting to sort out differences between combatant foreigners and local militants, but the talks collapsed when Maulvi Nazir asked for the surrender of all foreign militants residing in the region bordering Afghanistan (Dawn, March 24, 2007). In late January, two arrested members of the Haqqani Network revealed that up to 200 suicide bombers had infiltrated into Pakistan’s cities in preparation for the current wave of bombings (Khabrain [Lahore], January 28).

Two months ago, one of Sirajuddin’s most important commanders, Darim Sedgai, was reported killed after being ambushed by unknown gunmen in Pakistan, though spokesmen for the Haqqani Network claim that Sedgai is recovering from his wounds (The News [Karachi], January 28). Coalition forces in Kabul confirmed the killing of Sedgai, who was known as a powerful commander of the Haqqani Network, overseeing the manufacture and smuggling of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) into Afghanistan. These activities led U.S. forces to post a $50,000 reward for information leading to his death or arrest. A native of the North Waziristan agency, Sedgai was a follower of Jalaluddin Haqqani and fought under his command with the mujahideen in Afghanistan. Until his reported death in January, Sedgai was an important leader of the Haqqani Network and was considered to be a close friend of Sirajuddin Haqqani (Pajhwok Afghan News, January 28).

Conclusion

Afghan officials as well as Coalition forces in Kabul have cited Sirajuddin’s use of North Waziristan as operational headquarter for his alleged cross-border terrorist activities as one example of Pakistan’s inability to eliminate terrorist sanctuaries in its tribal areas. Though the Pakistan government regards these claims as baseless, it is known that two years ago Sirajuddin issued a circular urging militants to continue their “jihad” against the United States and the Karzai government “till the last drop of blood.” But in the same statement he pointed out that “fighting Pakistan does not conform to Taliban policy… those who [continue to wage] an undeclared war against Pakistan are neither our friends nor shall we allow them in our ranks” (Dawn, June 23, 2006). There are signs that this is no longer the policy of the Haqqani faction of the Taliban.

As the Haqqani Network has risen to the first rank of the Taliban insurgency it can be expected that U.S.-led Coalition forces in Afghanistan will continue to target Sirajuddin Haqqani and the rest of the network leadership. With such strikes now occurring on Pakistani soil the Haqqanis are emerging as a serious domestic problem for Islamabad. How it chooses to deal with the Haqqani Network threat will provide a test case for Pakistan’s role in the ongoing war on terror.