The Illicit Wildlife Trade in China and the State Response Following the Coronavirus Outbreak

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 5

By:

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 coronavirus (新型冠状病毒, xinxing guanzhuang bingdu) in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), wildlife trade and consumption have become a top issue in the country. The disease, which has caused 3,215 deaths in China and over 6,500 total deaths worldwide (per official figures, as of March 15), has been identified as a zoonotic virus (i.e., one originating in an animal species) with a possible point of origin in the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, Hubei Province (China Brief, January 17; WHO, February 28; Johns-Hopkins University, ongoing). China, as well as many other countries, suffered from the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003. [1] SARS was also zoonotic in nature: its origin was traced to civet cats (CDC, January 13, 2004), which are considered a delicacy among some mainland Chinese citizens.

Seventeen years have passed since the SARS epidemic, and it seems that history repeats itself. Experts in the field of infectious disease have warned that governments should take measures to regulate (or ban outright) the trade and consumption of many wildlife species. The Chinese government has taken several measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19, including a ban on the trade in wild animals—both those that are hunted or captured in wilderness areas, and those that are farmed by people. What lessons have the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and the Chinese public, learned about the potential consequences of the wildlife trade? This article examines the Chinese government’s policy response towards the wildlife trade in the wake of the COVID-19 epidemic, and what this might portend for the future.

The Illicit Wildlife Trade in China

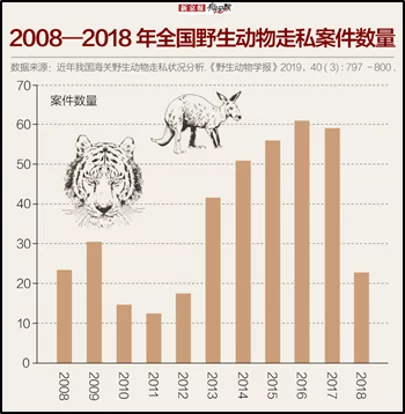

Black market wildlife trafficking is a major illicit business sector in the PRC—and while the PRC revised its Wildlife Protection Law in 2018, the outbreak of COVID-19 has demonstrated lax enforcement involving wildlife trafficking and smuggling (China News, March 2). A government-sponsored report has valued wildlife trade and consumption in China at 520 billion renminbi ($74 billion), involving a workforce of 14 million people (South China Morning Post, February 26). For the past ten years, Chinese customs authorities have recorded more than 390 wildlife trafficking and smuggling cases (an average of one case every nine days). The period with the highest level of recorded activity was between 2013 and 2017, with an average of 40 to 60 cases per year. Among all the provinces, Guangdong Province appears to have the highest level of trafficking in wildlife (or wildlife parts): bear paw, bear bile, tiger skin, ivory, and bats are all popular in the trafficking markets (Beijing News, February 29).

Among different types of wildlife, the single-most trafficked animal in the world is the pangolin, and China is the primary market. Pangolin scales are valued for their claimed medicinal properties, and their meat is considered a valuable delicacy. However, pangolins are also suspected of being an intermediate host of the COVID-19 virus. [2] Between 2007 and 2016, China authorities recorded 209 pangolin smuggling cases, including 2,405 live pangolins and 11,419 dead pangolins (Xinhua Net, January 18, 2017).

Many believe that this is only the tip of an iceberg. In one case from 2018, a group of Chinese citizens reported pangolin illicit trading activities to the Chinese authorities through a public account on WeChat, a popular instant messaging app. According to this report, the smuggling market price of a five-kilogram pangolin from overseas into China is 700 renminbi ($101) per kilogram; after re-sale within China, the market price soared to 4400 renminbi ($635) per kilogram. The price of a prepared pangolin dish on the table could be as high as 22,000 renminbi ($3174) per kilogram. To make more profits, Chinese smugglers sometimes use various unscrupulous means to increase the weight of pangolins—to include injecting foreign substances (such as flour, paint, cement, limewater) and chemical additives (sedatives, stimulants, and preservatives). The smugglers could increase the weight of a pangolin by up to 20% using the above methods. These notorious practices have posed threats to the health of Chinese citizens who consume pangolin products (Xinhua Net, February 24).

The CCP Leadership Directs a Crackdown on the Wildlife Trade

In a speech presented to the CCP Politburo Standing Committee on February 3, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping stated that the coronavirus has posted a significant challenge to the “Chinese state governance system and capability” (国家治理体系和能力, guojia zhili tixi he nengli). Xi pointed out that the “game meat industry” (野味产业, yewei chanye) is still a huge market and a potential hazard to public health (Qiushi, February 15). Xi asked relevant departments to combat the illicit wildlife trade—with responses that can be divided into three categories, as seen in the chart below:

| Legal Aspects |

|

| Policy Aspects |

|

| Social Aspects |

|

(Source: Compiled by the author, based on information from the CCP journal Qiushi)

The CCP has moved quickly since receiving Xi’s instructions. On February 24, the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee approved a “comprehensive ban” (全面禁止, quanmian jinzhi) on illegal wildlife trafficking and the consumption of wild animals. The move has several goals and associated slogans, including “completely ban the eating of wild animals,” “eliminating the bad habits of eating wild animals,” and “cracking down on the illegal trade in wildlife.”

On the policy front, Li Zhanshu, chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, urged rigorous implementation of the ban in order to provide a legal foundation for safeguarding public health, preserving China’s natural ecology, and improving the country’s image (Global Times, February 25). In regards to the legal aspects, the NPC Standing Committee has listed the Wildlife Protection and Animal Epidemic Prevention Law (动物防疫法, Dongwu Fangyi Fa) as an immediate legislative priority for this year’s legislative session. Furthermore, the NPC Standing Committee has also indicated plans to fast-track a Biosecurity Law (生物安全法, Shengwu Anquan Fa). This latter law was submitted to a bimonthly session of the NPC Standing Committee for deliberation on February 21 (Xinhua Net, February 24).

Since the announcement of the comprehensive ban on February 24, the Chinese authorities have inspected at least 350,000 markets, restaurants, and hotels nationwide, and have seized almost 40,000 wild animals. The Chinese government has further closed around 17,000 on-line stores and accounts, and has deleted more than 750,000 online messages involving the wildlife trade (Beijing News, February 29).

Underlying Challenges

The trading and consumption of wild animals in China is a multibillion-dollar industry, and merely announcing a ban and introducing new legislation has proved to be inadequate. One key issue is to more effectively enforce existing laws against wildlife trade and consumption. Under the PRC’s Wildlife Protection Law, the provisions of Article 30 have already prohibited the consumption of “nationally protected wild animals” (国家重点保护野生动物, guojia zhongdian baohu yesheng dongwu). However, enforcement of this law has been problematic: for example, the pangolin is one of the “nationally protected wild animals,” but the estimated total consumption of pangolin scales was 26,600 kilograms between 2008 and 2015. It is difficult for authorities to trace the source of smuggled animals and animal parts, whether it is from cross-border smuggling or from game hunting (Daily Headlines, January 23).

A second serious challenge lies in raising public awareness of the problems associated with wildlife consumption. Eating wildlife products is an element of traditional Chinese culture that has existed for centuries. Many Chinese people not only consider wild game meat to be a delicacy on dining tables, but also believe that eating wildlife parts is an important element of, or supplement to, traditional Chinese medicine (食补中药, shibu zhongyao). Although laws have prohibited such consumption, continued demand is likely to push the wildlife trade back into black markets. The outbreak of COVID-19 has revealed both the fragility of the Chinese public health system, as well as low public awareness regarding the risks of the wild animal trade. It remains to be seen how successful the Chinese government will be in educating its people and raising public awareness in the long run.

Conclusion

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the Chinese government has been striving to preserve its national image by tightening internal control over the wildlife trade. It is still early to judge how effective the measures of the “comprehensive ban” will be. The critical points remain law enforcement at the local and community level, and changing people’s traditional cultural conceptions regarding precious wild animals. China has long been the world’s largest market for wildlife trade and consumption. If the Chinese public has learned a lesson this time, there is a chance that the whole illicit industry will go down. However, if there is still a substantial domestic demand in China—even under tightened measures pushed by the central government—the illicit market price of wildlife will only rise in the future, and the trade will continue.

Leo Lin is a PhD candidate at the University of Southern Mississippi. His work focuses on Indo-Pacific security, non-traditional security, and Chinese grand strategy.

Notes

[1] Susan M. Puska, “SARS 2002-2003: A Case Study in Crisis Management,” Chinese National Security Decision-Making Under Stress (Scobell and Wortzel, eds.), U.S. Army War College (Sep. 2005), pp. 85-100. https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/1726.pdf.

[2] Pangolins have not been conclusively identified as the species through which COVID-19 transmission to humans occurred, but this is a prominent theory under discussion among scientists. For one example, see: Zhang Tao, and Wu Qunfu, and Zhang Zhigang, “Probable Pangolin Origin of 2019-nCoV Associated with Outbreak of COVID-19,” Current Biology (Feb. 2020). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542586.