The Jubaland Initiative: Is Kenya Creating a Buffer State in Southern Somalia?

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 17

By:

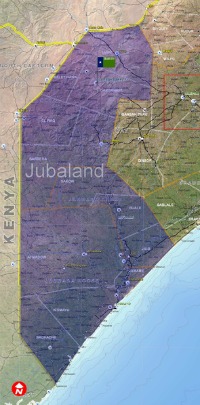

Several reports circulated through the international media in early April indicating that a new semi-autonomous state, tentatively named Jubaland (or alternately “Azaniya”), would be created in southwestern Somalia to contain the Somali militant outfit Harakat al-Shabaab. Jubaland is purportedly being created by Kenyan authorities to keep al-Shabaab fighters far away from the border of its North Eastern Province with Somalia where recent clashes and cross border incursions from both belligerents have occurred.

Jubaland would supposedly be composed of three Somali regions: Lower Juba, Middle Juba, and Gedo. The state would be headed by a professor named Muhammad Abdi Muhammad “Gandhi,” who briefly served as defense minister in Mogadishu in February 2009 (Garowe Online, February 21, 2009). Jubaland would have as its capital the Indian Ocean port of Kismayo, which was for a period of time under the firm control of an alliance between al-Shabaab and the Mu’askar Ras Kamboni militia (al-Jazeera, December 21, 2008). Professor Gandhi, as the former defense minister is commonly known, has outlined his strong desire to create a new, stable sub-state entity, analogous to Somaliland and Puntland, in order to “liberate Jubaland from extremists” (Daily Nation [Nairobi], April 3).

Beyond the argument for defending Kenya’s borders from foreign militants, Kenya’s ethnic Somali majority in North Eastern Province has historically been threatened by the Greater Somalia movement and deeply rooted notions of pan-Somali irredentism. From November 1963 to April 1968, a pro-Somali movement fought government forces in what was then called the Northern Frontier District. Known as the “Shifta War,” the conflict pitted Jomo Kenyatta’s Kenya in alliance with Haile Sellasie’s Ethiopia against ethnic Somali rebels and their backers in the Republic of Somalia. [1] Nairobi is not threatened solely by al-Shabaab forces crossing into Kenyan territory to stage attacks, but also fears a resurgence of ethnic Somali nationalism within its borders and the incitement of over 300,000 Somali refugees currently subsisting inside Kenya. Al-Shabaab spokesman Shaykh Ali Mahmud Raage recently rattled his saber at the Kenyan state by claiming Nairobi was knowingly allowing Ethiopian regular troops to stage offensive operations against al-Shabaab from the border town of Mandera (Reuters, February 27). Al-Shabaab wasted little time in making good on its threats by launching a bomb and gun attack on Mandera just two weeks later (The Standard [Nairobi], March 15). Beatrice Karago, counselor at the Kenyan Embassy in Addis Ababa told Jamestown the embassy has no knowledge of the entrance of Ethiopian troops into sovereign Kenyan soil as asserted by al-Shabaab. When asked if the Jubaland initiative had been a possible thorn in the side of Kenyan-Ethiopian relations, Karago glossed over any possible policy rift, replying: “Kenya and Ethiopia have always had good relations.”

Differing from the official Kenyan account of Kenyan-Ethiopian relations, a U.S. Embassy cable released by the Wikileaks site states: “[Prime Minister] Meles [Zenawi] said the GoE [Government of Ethiopia] is not enthusiastic about Kenya’s Jubaland initiative, but is sharing intelligence with Kenya and hoping for success. In the event the initiative is not successful, the GoE has plans in place to limit the destabilizing impacts on Ethiopia.” [2] In describing the unilateralist nature of Ethiopia’s 2006 failed military intervention in Somalia, Prime Minister Zenawi was hesitant to predict a successful outcome for any political or military intervention in southern Somalia by the Kenyans, at least from a tactical standpoint. If Kenya’s Jubaland initiative was to ever get off the ground and have a modicum of success, it is likely that Addis Ababa would publicly lend the government of President Emilio Mwai Kibaki and a nascent Jubaland administration tentative support coupled with further repression of indigenous ethnic-Somali separatists such as the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) in Ethiopia’s vast Ogaden Region.

Another significant factor that should not be overlooked is Kenya’s long-standing Somali refugee crisis. An additional reason for Nairobi to solidify a new semi-autonomous region inside Somalia is to stem the steady flow of displaced people fleeing the non-stop violence in that country. Kenya, as an impoverished host country, views the refugees as both a large financial burden and a security liability. Francis Kimemia, Kenya’s permanent secretary for internal security, believes that at some point the refugees must be repatriated to Somalia, where African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) peacekeeping troops or forces loyal to the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) should be responsible for their well-being. Jamestown was unable to reach AMISOM for comments at its Addis Ababa headquarters. However, an official working in an adjacent Sudanese security affairs office stated that he believed the implementation of a purely Kenya-driven reorganization of the Somali state lacked solid prospects. Despite the difficulties ahead, Kenya is being forced to act pragmatically. According to Kimenia: “The long-term option is to urgently stabilize Somalia since Kenya may not host the refugees forever” (Daily Nation [Nairobi], April 20). Kenya would prefer the Somalis be internally displaced inside Somalia rather than remain in fetid conditions in its northeast, where they pose what it believes is a possible security risk in regard to radicalization and cross border arms smuggling, among other issues.

A critical factor for Kenya’s wider security structure, particularly in the wake of the July 11, 2010 Kampala bombings attributed to al-Shabaab, is the very real threat posed by the now transnational Somali Islamists against Kenya. Al-Shabaab has become hostile to Kenya for what it believes to be Nairobi’s direct support for the TFG. [3] Simultaneously, the Mogadishu-based TFG is wary of the Jubaland initiative because it views any further devolution of power in Somalia as an existential threat to its authority, undermining its ability to bring any kind of future peace to Somalia proper. TFG Prime Minister Muhammad Abdullahi Muhammad further views the Jubaland initiative as a blow to Somali-Kenyan bilateral relations and opposes its formation (Raxanreeb, April 7).

Though the TFG views, perhaps correctly, that the further dissection of an already truncated Somali state greatly erodes any chance of reconciliation amongst constantly feuding parties, Nairobi believes it is acting to contain a very real threat along and inside its borders. In the eyes of the Kibaki government, the creation of Jubaland may isolate the seemingly pointless machinations of the TFG in its AMISOM-protected Villa Somalia compound, but it will greatly assist in buffering Kenya from al-Shabaab attacks. Kenyan patience with Somalia’s unending internecine strife and the relative impotence of the TFG is running out.

Although the African Union supposedly backed the Jubaland initiative, Jamestown met with Shewit Hailu, an AU official in Addis Ababa, who stated that the AU had taken no official position, nor made any official statements regarding the political reordering of southwestern Somalia’s perennially troubled geography (see also The Standard [Nairobi], April 3).

While al-Shabaab militants increase tension in the border region with attacks inside Kenya and reported engagements with Ethiopian troops, the TFG’s governor in the southern Gedo region, Muhammad Abdi Kalil, said his men under arms are at war with al-Shabaab (Shabelle Media Network, April 24). Kalil claims his forces are preparing to mount a counteroffensive against al-Shabaab, though it is unclear just what such an offensive would look like considering the TFG’s inherent military weaknesses in the region. Adam Diriye, an MP in the beleaguered TFG administration, called on the people of Middle and Lower Juba to revolt against al-Shabaab, describing the TFG forces in Gedo as “heroes” (Shabelle Media Network, March 15). From a security standpoint, the three regions would, at the very least, have to largely evict al-Shabaab fighters from their respective administrative centers in order to consolidate a future Jubaland – no easy task at present. According to David Shinn, former U.S. ambassador to Ethiopia: “Until the supporters of the Jubaland State can take control of the area from al-Shabaab, it is nothing more than a creation on a map with elected representatives sitting in Nairobi.” [4]

Notes:

1. Nene Mburu, Bandits on the Border: The Last Frontier in the Search for Somali Unity, (Trenton, New Jersey: Red Sea Press, 2005), p. 153.

2. To view the original document, see: “Under Secretary Otero’s Meeting with Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi – January 31, 2010,” https://www.wikileaks.ch/cable/2010/02/10ADDISABABA163.html#par4.

3. Barako Elema, “Insurgency in Somalia and Kenya’s Security Dilemma”, Institute for Security Studies [Pretoria], March 31, 2011.

4. Author’s email exchange with Ambassador David Shinn, April 19, 2011.