The Spirit of Xu Sanduo: The Influence of China’s Favorite Soldier

Publication: China Brief Volume: 13 Issue: 15

By:

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a long history of promoting its own group of moral heroes. Sino-Japanese War martyrs and hardworking small-town cadres have all been used by the government to push social values since the founding of the People’s Republic. With an ongoing rectification campaign and a “back to core values” attitude from the state-controlled media, CCP heroes such as humanitarian soldier Lei Feng are yet again being trotted out for the public (“Another Lei Feng Revival: Making Maoism Safe for China,” China Brief, March 2, 2012).

This time, however, the public does not appear to be interested in the CCP’s moral star. A recent film showing Lei Feng’s early life has become a major flop at the Chinese box office and the lack of interest begs the question of who will take his place (Xinmin Wanbao, March 7). The disaster of “Young Lei Feng” indicates many of these old stalwarts of Chinese Communist propaganda are failing. Lei Feng and his fellows are in clear need of an update and the choices the Communist leaders make—by keeping Lei Feng in the pantheon or creating more updated versions—will say a lot about how sensitive the Party can be to modern Chinese sensibilities. The irony is that such an icon already exists and is readily embraced by the public: Xu Sanduo. Despite being a name that wields enormous cultural cachet, Xu is not even a real person, but a character from a popular TV series almost seven years ago.

Overview of Soldier’s Sortie

The series, Shibing Tuji or, Soldier’s Sortie, follows a fairly straightforward plot. A young man, Xu Sanduo (whose very name implies that he was an extra, unwanted child) from the countryside is conscripted for two years, where he hopes that he will be able to make something of himself. His strong regional accent, lack of formal education or family support make him a hopeless recruit—leading to some hilarious antics and gut-wrenching moments. Frustrated with Sanduo’s apparent incompetence, his superiors quickly shunt him to a second-tier unit out in hinterlands, where eventually his hard work, good nature and indomitable spirit shine through. He comes to be regarded as a talented, if still somewhat goofy, recruit. Given a slot at the Special Forces training course, Sanduo passes where others fail and makes a name for himself. Later, during combat operations against drug smugglers he sees death up close and has to deal with the psychological consequences. He eventually recovers and returns to the Special Forces unit.

In contrast to the comically flat characters and repetitive plot lines of most Chinese military dramas, Soldier’s Sortie dealt with real world issues at both a personal level and within the Chinese military. The show’s commitment to realism and lack of convenient plot devices is what made it have such a large impact on Chinese audiences. While several series have since sought to replicate the success of Soldier’s Sortie, the series has remained consistently the most popular of the genre and retained a high rating on Chinese websites. For example, on Douban.com—the Chinese equivalent to the English-language Internet Movie Data Base—the show received an 8.9/10, a very high score. There is no omnipresent host of “bad guys” belonging to an easily identifiable oppressive power. Unresponsive bureaucracy and incompetence, exemplified by uncomprehending uniformed civilians (wenzhi renyuan) and soldiers just biding their time until their contracts are up are the clearest negative characters. In an early episode for example, the propaganda department of the regiment Xu Sanduo is first assigned to is clearly viewed as being far out of touch with the realities of soldiering. The culture clash between the desk-bound and field elements of the military is a recurring theme. This stands in contrast with enemies in the form of heavily-armed drug smugglers, who appear later in the series to serve more as a test of the main characters mettle rather than a threat or moral example.

Throughout the series, Xu Sanduo displays a limited understanding of the broader changes occurring around him, often to the frustration of his platoon and squad mates. He nevertheless soldiers on, invoking a philosophy of “you yiyi jiushi haohao huo, haohao huo jiushi zuo hen duo you yiyi de shi,” roughly translated as "to live well is to do meaningful things, doing many meaningful things is to live well". This phrase has become a motto of sorts, repeated more naturally and more seriously than official slogans (Xinhua, January 9, 2008).

An Unlikely TV Phenomenon and the Spirit of Xu Sanduo

With a number of female bit-parts that can be counted on one hand (two, in the authors recollection), and hence no real traditional Chinese love story, one might have anticipated Soldier’s Sortie to be a flop. One Shanghai paper marveled at how a TV show without “beautiful women, celebrities or a love story" could become so popular (Liberation Daily, December 4, 2012). Yet, despite a lack of these ingredients, it turned into a sensation, becoming one of the most popular Chinese television series. By all indications, the series did not benefit from much official help or promotion. In fact, it was first broadcast on Shanxi provincial television in December of 2006 with mixed results, but was then swapped as a digital file among fans before being rebroadcast to larger audiences. Subsequent attempts to cash in on the success of Soldier’s Sortie, such as I am a Special Forces Soldier (Wo shi tezhongbing) have been strongly derided for being poor copies. The series wields such large cultural cachet due to Chinese military enthusiasts (junmi) who form a large viewer demographic.

The series has had an impact far beyond just entertainment. At a time when the Chinese military is having an ever-greater difficulty attracting recruits who fit physical and educational requirements, Soldier’s Sortie inspired many students to challenge themselves mentally and physically by joining (Frontier Police News, June 29, 2010). Perhaps more importantly is what Soldier’s Sortie has done culturally.

In a society that is more and more raised on KFC and McDonalds and to whom the military is no longer the only ticket off of the ancestral farm or out of the second-tier city, military life had lost much of its appeal, and the quality of PLA recruits had dropped significantly. Obesity, for example has become a major problem. The issue became so pressing that in 2011, the PLA altered its weight standards for new conscripts in a bid to increase recruitment. Financial incentives also were added to help attract more educated recruits (Global Times, November 3, 2011).

The biggest issue in recent years, however, has been cultural. Recruits often have unrealistic expectations of a cushy time in training. The one child policy and dramatically-improved standards of living created a culture of entitlement. In one example of such conflicts, recruits reportedly offered to pay to have their own rooms during training (Southern Weekend, March 3, 2011).

The unvarnished, frank portrayal of ordinary Chinese soldiers lives in Soldier’s Sortie directly challenged this sort of attitude by having a main character, who by no means a natural, chose to work hard and challenge himself because it was the right thing to do. One illustrative moment occurs early in the series. Despite having been sent to a remote unit known for its lax standards and status as a dumping ground for lackluster soldiers. Sanduo goes to great pains to continue training, eventually gaining the respect of his unit and inspiring his squad leader to regain honor. Interestingly, Xu Sanduo’s perseverance in the face of adversity has made him a role model at a time when Chinese perceive themselves as being too entitled and used to comfort. Xu Sanduo, or rather, “Xu Sanduo’s type,” has become an easily recognizable persona and those who are hard working are therefore often labeled as “Xu Sanduo de yangzi” or “Like Xu Sanduo” (Xinhua, May 10; China Military Online, May 30, 2012; People’s Armed Police News, January 2, 2012).

In much the same way that Lei Feng’s “spirit” is invoked in official media, Xu Sanduo’s name similarly is referenced to evoke certain feelings of hard training and camaraderie. The state media organization Xinhua periodically does picture or news spreads about various units “displaying the spirit of Xu Sanduo” (Xu Sanduo de jingshen). The name Xu Sanduo has such a strong ability to evoke certain ideas that it is commonly used in military-related media, unsurprising given the series widespread popularity within the Chinese military (PLA Daily, March 1). Like a social meme then, the character and his name have taken on significance far beyond the series itself. Recent reporting on volunteers and soldiers involved in rescue operations after the recent earthquake in Sichuan reflects the power of Xu Sanduo’s image. One reporter interviewed several soldiers who said they closely identified with Xu Sanduo’s background and experiences. Sanduo has become a popular—and not entirely unkind—nickname for those with a strong regional accent and perhaps a slower way of doing things. Another interviewee, Liu Xudong, said he joined the military as a result of a friend showing him Soldier’s Sortie (Sichuan Online, May 6). That is a significant endorsement of the power of a fictional character that is not the direct product of a propaganda department.

A Realistic View of the PLA

Central to its social impact is the degree of realism used throughout the series. Soldier’s Sortie takes place during a dynamic time within the PLA. While the director certainly took creative license with some aspects of the series, Soldier’s Sortie is notable for its illustration of real issues. Ultimately, the PLA’s modernization provides the backdrop to the series. Between 2005 and 2006, the approximate setting of series, the PLA completed an important round of modernization that included major reductions and reorganization of personnel. Other important issues such as mechanization and informatization—the two keystones of China’s military modernization over the last 20 years—are all dealt with in the series. After proving himself in a backwater unit Xu is assigned to an armored reconnaissance unit attached to the “Steel 7th Company.” Various training exercises involving the Type 89 armored personnel carrier used by such recon units are shown as are helicopter operations. Eventually, the “Steel 7th” is stood down and reorganized during the personnel cuts completed in 2005. This itself becomes a major plot point. At one point the regiment’s commander emphasizes that modern vehicles require fewer men (reflecting, for example, the shift to automated loading cannons for main guns in modern PLA tanks) and that more specialized skills must become standard (“Reforming the People’s Liberation Army’s Noncommissioned Officer Corps and Conscripts,” China Brief, October 28, 2011). The pace of modernization and the inconsistency in levels of equipment between units it creates is apparent. Second-tier or garrison units are shown as having much older types of equipment in contrast to newer and more elite units. For example, the series shows the former using Type 87 woodland camouflage and the Type 81 assault rifle, while the latter use the digitized camouflage Type 07 uniform and type QBZ-95 bullpup rifles. Soldiers Sortie’s usefulness, however, goes beyond just illustrating different types of equipment.

The series addresses sensitive issues rarely seen in the media. The human consequences of the PLA’s modernization are clearly illustrated. New emphasis on technical skills for example, is having a generational-turnover effect by pushing out soldiers without them ("Noncommissioned Officers and the Creation of a Volunteer Force," China Brief, September 30, 2011). Older soldiers, who are without specialized knowledge or skills, are drummed out of the service. In the series, Xu’s squad leader, an older enlisted man, is given the chance to leave the PLA with a degree of honor despite having lost his heart for real soldiering years ago. In real life, there would be a question of what a soldier with years of service under his belt would do after returning to his home. More disciplined than his neighbors, often nursing a grudge against the system, such a person would be a strong candidate to get involved in local politics. This perhaps explains why many protests about other issues–environmental or political–often have former military leaders at their head.

Soldiers Sortie pulls few punches when addressing issues of poor leadership and corruption. Several officers and enlisted non-commissioned officers are clearly singled out as being incompetent. Others are intimated as having been the benefit of nepotism, in both cases a shift from typical black and white characterizations. The commander of the 7th Company, for example, having thought he achieved his position on merit alone, is shocked to discover that his father’s identity and level influence (as a high ranking officer) is well known throughout the unit. Years later, these issues have yet to be fully addressed. Chinese National Defence University professor and Senior Colonel Liu Mingfu famously pointed to corruption as being the PLA’s biggest weakness in his book Why the PLA Can Win (Jiefangjun weishenme neng ying) (Ming Bao, [Hong Kong] March 28, 2012). The PLA certainly has been a target for austerity measures and most recently, an audit of its property assets (China News Net, June 22; “Commander-in-Chief Xi Jinping Raises the Bar on PLA ‘Combat Readiness’,” China Brief, January 18). Soldiers Sortie is not a political series, yet its coverage of technical and political issues in realistic ways have helped cement its position as a popular series.

Even if many of the military modernization elements seem a little outdated to seasoned PLA watchers, the series has become a touchstone for Chinese civilians to understand the Chinese military in a country where discussion of many topics is quite limited. Revealingly, in a rare interview with officers from a PLA special forces unit, a reporter from state television several times asked the officers to compare their experiences with those shown in Soldier Sortie, even asking which character they related to the most (Xinhua, April 1, 2008). In the interview it is clear that most of her knowledge about such matters comes from familiarity with the series. Though the PLA is accorded a high place within Chinese society, such attitudes are not rare.

Conclusion

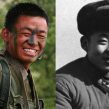

While not a documentary by any means, the series should be a standard for China Watchers and researchers of the PLA for the perspective it gives on these issues. Without an English subtitled version, for now, Soldier’s Sortie will remain accessible only to those with Chinese language skills. The wealth of useful information and its continuing cultural cachet should make it a high priority for language students or those with an interest in Chinese military affairs. The image of an earnest, grinning Xu Sanduo will certainly remain as an inspiration for Chinese to join the ranks of the PLA.