The Thorny Road to the Kremlin’s Desired Yalta-2021

The Thorny Road to the Kremlin’s Desired Yalta-2021

Russian top officials—in particular, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (RIA Novosti, April 27) and Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev (Kommersant, April 8)—have for weeks been talking about the deepening crisis in Russia’s relations with the United States while at the same time expressing some hope that an improvement could still happen. Both Patrushev and Lavrov imply Russo-US relations are as bad as during the Cold War, though with less predictability or mutual respect. Still the two men insist there are no major ideological differences today, since Russia is not trying to destroy the Western way of life by spreading some form of Communism. This apparently implies the present confrontation is superficial and could perhaps be resolved if Washington and its allies curtail their aggressive stance against Moscow as well as recognize Russia’s “legitimate” national security and sovereign rights, including the right to defend Russian-speakers wherever they live. If the US and its cohorts do not stand down, the situation “could get worse than a Cold War,” according to Lavrov (RIA Novosti, April 27)—i.e., go from “cold” to “hot.”

In turn, Western leaders, including US President Joseph Biden and his Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, have been talking about stabilizing relations with Russia. While insisting Moscow must pay a price for its “bad behavior”—alleged cyberattacks, election interference, human rights violations, aggressive actions in Ukraine and so on—the West has expressed the desire to work with the Kremlin on subjects of mutual interest, like nuclear arms control, fighting Islamist terrorism, controlling the pandemic, tackling global climate change and so on. In Washington, many believe China, with its growing economy already almost equal to the US, is potentially a much more formidable foe than the stagnating, oil and natural gas–exporting Russia with its limited financial and industrial resources. Top US officials are working with the Kremlin on fixing a date and place for a possible Biden–Vladimir Putin summit, sometime in June 2021 and somewhere in Europe (Interfax, May 6). The negotiations have turned out to be complicated. Moscow has indicated “interest” but has not yet fully committed to the meeting. Still, there is hope such a summit could defuse growing tensions or at least postpone (if not prevent) a major outbreak of fighting with Ukraine. As the summit is being prepared, the Western powers hope Russian forces gathered on the Ukrainian border may eventually withdraw.

Tit-for-tat expulsions of diplomats between Moscow and the West, along with Russia’s recent restrictions preventing “unfriendly nations” like the US from hiring locals to help run their embassies in Moscow, have left diplomatic relations in tatters. The US embassy stopped issuing non-immigrant visas to Russians in Moscow, and its effectiveness as a representative of the US government has been diminished. Lavrov said he offered Blinken the “zero option”—to reverse all restrictions imposed by both sides since 2016, including the seizure by the US authorities of Russian diplomatic country residences close to New York and Washington (RIA Novosti, April 27).

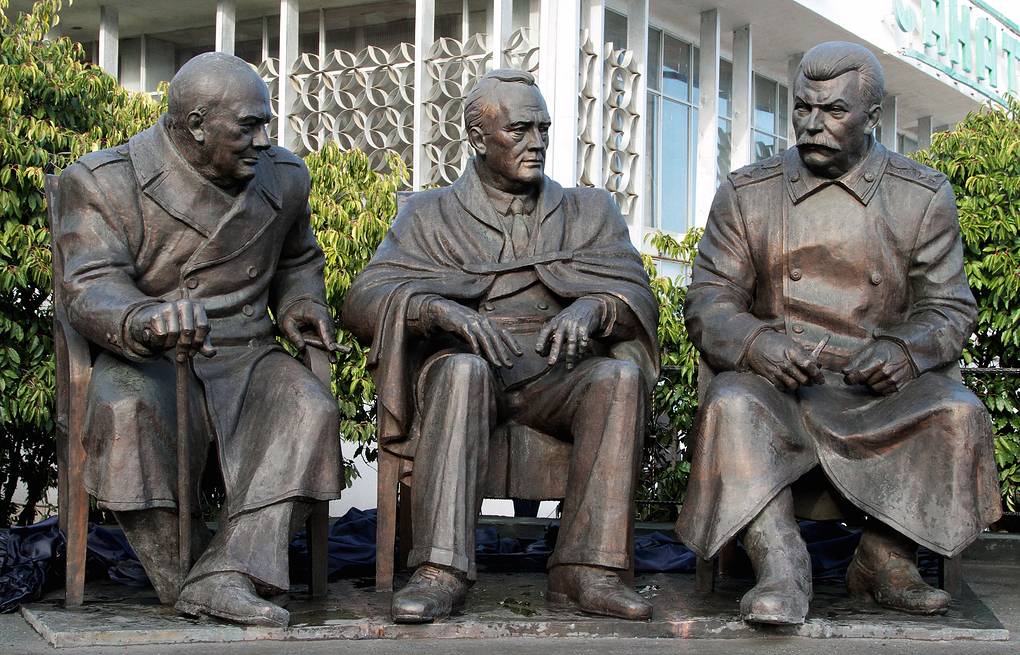

Apparently, Moscow’s overall idea of mending fences is a grand “zero option”—returning to things as they were before 2014. The Kremlin expects the West to end all sanctions or at least most of them. Russia, in turn, would lift its anti-Western restrictions, while at the same time keeping Crimea and a foothold in Donbas. Seasoned and decorated Russian (Soviet) diplomat Grigory Karasin (71) was for, many years, a state secretary and deputy foreign minister. In 2019, Karasin was moved from the foreign ministry to the Federation Council (upper chamber of the Russian parliament)—appointed senator representing Sakhalin Oblast, while continuing to work to keep open an unofficial channel of negotiations with Tbilisi. In March 2021, Karasin was elevated to chair the Federation Council’s Foreign Relations Committee. In an interview after his promotion, Karasin expressed the need for Russia and the West to negotiate a new Yalta-style accord—like the 1945 summit between Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, who together de facto carved up Eurasia into spheres of interest at the end of World War II. According to Karasin, Yalta-1945 provided stability and predictability to generations of mankind, “though it was criticized.” A new “Yalta-2021,” could do the same and prevent another world war. Putin is promoting that idea by proposing a special summit of the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, according to Karasin (Kommersant, April 12).

It has long been Moscow’s goal to put together some kind of new Yalta agreement or a “Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact 2.0” to carve up Eurasia, including Ukraine (see EDM, February 26, 2015), but apparently, Karasin spelled out this political priority a bit too bluntly. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact has been significantly rehabilitated in Moscow in recent years, though it is still assessed to have been a bad deal with an untrustworthy enemy. In contrast, “Yalta” was an antifascist summit that may have bad connotations in Central and Eastern Europe, but certainly not in Moscow (Rosbalt, January 16, 2020).

Though, is the West and, in particular, the Biden administration ready to sign on to a Yalta-2021 at all? Moscow may be growing restless to secure a deal soon and has signaled it will not wait much longer for Washington to recognize the need for a geopolitical compromise. Forcing through a Yalta-style deal in 2021 would, therefore, seem obligatory. The problem with the planned Biden-Putin summit may not be the venue, but the true agenda; and for the Russian leader, it will be important to be able come to the table and talk from a position of strength. Putin has been brandishing an array of new nuclear superweapons since 2018 and claims Russia has become a “world leader in modern weapons” (see EDM, April 22). In its nation-wide mass mobilization of “over 300,000 soldiers” and of heavy weaponry in March–April, under the pretext of “battle readiness tests,” Russia sought to demonstrate its ability to fight and win a big conventional regional war with Ukraine, while ready to take on the US and its allies in a global (nuclear) conflict (Militarynews.ru, April 29). But this saber rattling seems not to have moved Washington an inch toward accepting a Yalta-2021 or Molotov-Ribbentrop 2.0 agreement.

The “dumb” Americans, as Lavrov now crudely calls them, do not understand (RIA Novosti, April 8). And the Kremlin is left wondering whether the troops still left along the Ukrainian border following their “battle readiness tests” might need to demonstrate their capabilities in real combat for the upcoming summit with Biden to be a success. Though if Russia further invades Ukraine, would Biden be willing to meet Putin at all?