The Unseen Hand: Saudi Arabian Involvement in Yemen

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 12

By:

Executive Summary:

The future of Yemen is inextricably linked to the stability and security of Saudi Arabia. With key figures in Yemen defecting to the opposition – including the ambassador to Saudi Arabia – and violence between the Saleh regime and anti-government forces escalating, Saudi Arabia faces a major challenge in managing its policy toward Yemen due to its own internal divides as well as the rapidly deteriorating conditions in its neighbor to the south. Like other regional powers, Saudi Arabia is scrambling to assess, manage and, if possible, contain the rapid rate of political change in the region, especially in Yemen. Unlike other countries, however, Saudi Arabia’s future is intimately linked with that of Yemen, a situation that poses a potential danger to the Kingdom. Saudi Arabia has historically had a hand in the internal affairs of Yemen, and a policy of buying influence among the tribal powers, as well as lesser figures, has long formed the backbone of Saudi foreign policy in Yemen. Following an appeal by Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the Saudi government finds itself acting as the mediator between the Saleh regime and opposition forces. Despite the complex and at times contentious relationship between Saleh and Saudi Arabia, the Saudis cannot afford the departure of Saleh and the chaos that would undoubtedly result in Yemen. Additionally, Saudi fears of the Houthi movement along its border with northwest Yemen and the possibility of the Houthis consolidating their power in the region through the fall of Saleh provide even more incentive to the Saudis to take an active role in Yemen’s political crisis.

Introduction

The founder of modern Saudi Arabia, King Abd al-Aziz ibn-Saud (1876-1953) is purported to have said on his deathbed, “the good or evil for us will come from Yemen.” [1] The quote, regardless of its authenticity, accurately reflects the great importance and potential danger that Yemen poses to Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia has a long and complex history of involvement in Yemeni politics and this is unlikely to change. The future of Yemen, whatever that may bring, is intimately linked with that of Saudi Arabia and its influence in the country.

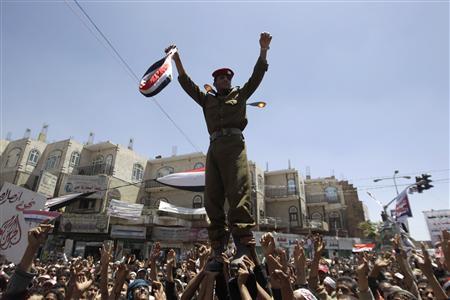

Faced with an ever increasing number of defections from his government and the military, Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh called on Saudi Foreign Minister Saud al-Faisal to mediate between his government and the anti-government protesters. On March 21, the Yemeni Foreign Minister, Abu Bakr al-Qiribi, was dispatched to Riyadh with a letter from Saleh (Asharq al-Awsat, March 21). This came after Yemen’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia joined many of his colleagues around the world and defected to the protesters. Publicly, Saudi officials have maintained the line that the crisis in Yemen is an internal matter. However, behind the scenes, the Saudi government is deeply involved in negotiations with Yemen’s tribal, political, and military leaders over the future of the regime and the country.

An Unruly Neighbor

Relations between the al-Saud dynasty and Yemen began with an al-Saud led attack on the Zaidi Imamate in 1803 that ended in Saudi forces pushing into parts of the Tihama region along Yemen’s Red Sea coast. Saudi expansion was brought to an end in 1818 when forces under Egyptian Viceroy Muhammad Ali Pasha reestablished nominal Ottoman control over the Hijaz and parts of Yemen. However, in 1926, Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud established a protectorate over the region of Asir along the Red Sea coast. Asir was once part of “Greater Yemen” which included parts of what are now the Saudi provinces of Asir, Jizan, and Najran. In 1932, Imam Yahya of Yemen moved his forces into the border region of Najran, but Saudi forces countered two years later with a major offensive that drove Yahya’s forces out of the region. The defeat led to the Treaty of Taif in which Imam Yahya recognized Saudi claims to Asir, Najran and Jizan. [2]

For roughly the next 30 years, Yemeni-Saudi relations were largely free of the upheaval that characterized much of the first three decades of the 20th century. In 1962, Imam Muhammad al-Badr, who had just claimed the title of Imam upon the death of his father Imam Ahmed, was overthrown by a military coup backed by the Arab nationalist regime of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser. Imam al-Badr and other princes from the Hamid al-Din family retreated to the mountains of northern Yemen and marshaled their forces to fight the Egyptian backed Republican forces. Yemen quickly became the stage for a proxy war between Nasser’s Egypt and the monarchist al-Saud regime, which feared Nasser’s Arab nationalistic rhetoric and expansionist agenda. More than 50,000 Egyptian troops were deployed to Yemen to help fight the Saudi-backed Royalists.

The Republican coup against al-Badr almost, albeit indirectly, led to the collapse of the House of Saud. Reform minded factions within the Saudi royal family supported some of the republican/nationalist ideals and wavered in their support for the Royalists, who sought the restoration of the imamate. Most importantly, elements within the Saudi military supported the idea of republican/nationalist influenced reforms. The political upheaval in Yemen led to a dramatic reshuffling of the government in Saudi Arabia. The conservative faction within the Saudi royal family that supported the status quo sidelined the reformers and cautiously supported the Royalists with arms and money. The hard fought civil war in Yemen began to wind down in 1967 but was not officially concluded until 1970. The Saudis were forced to recognize the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and began providing financial support to the new state while maintaining its long standing political and financial ties to many of Yemen’s most important tribal figures – notably the al-Ahmar family which heads the Hashid tribal confederation.

In south Yemen, what became the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) gained its independence from Great Britain in 1967. The move in south Yemen towards Marxist/ Leninist ideologies presented even more of a problem for the conservative monarchist government of Saudi Arabia. Until Yemen’s unification in 1990, Saudi foreign policy in Yemen was largely three pronged: contain and counter the threat of the expansionist PDRY, keep reform-minded leaders in the YAR in check and thwart efforts aimed at unification of the two countries. Saudi efforts to influence policy and events in the PDRY were largely failures, but it was far more successful at exerting influence in the YAR.

Saudi involvement in the downfall of both YAR President Abdul Rahman al-Iryani (1967-74) and his successor Lieutenant Colonel Ibrahim al-Hamdi (assassinated in 1977) is widely suspected by many Yemenis and scholars. Al-Hamdi remains a popular figure in Yemen and a few posters with his portrait pasted on them have been carried by anti-government protesters in Sana’a. Though unsupported by evidence, the popular belief in Yemen is that the Saudis played a part in al-Hamdi’s assassination. This belief was reiterated by a few of the protesters camped out near Sana’a university when asked by Jamestown about their views on Saudi Arabia.

Saudi relations with President Ali Abdullah Saleh are complex to say the least. Saleh has proven to be as adept at managing the Saudis as he has the tribes and tribal leaders. Shortly after taking power, he moved to counter the Saudi stranglehold on his arms supply by signing a $600 million arms deal with the Soviets, despite the fact that they were also backing his enemies in the PDRY. At the same time, Saleh maintained his reliance on the tribal system in north Yemen and did not act overtly to strengthen the central government to the disadvantage of the tribes. This policy pleased the Saudis since they had sway over the tribal leaders.

Yemeni-Saudi relations deteriorated markedly in the run up to the first Gulf War (1990-91). Yemen, which held a seat on the UN Security Council, failed to vote in favor of authorizing military action against Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. This miscalculation on the part of Saleh and his advisors cost Yemen dearly in both economic and political terms. Saudi Arabia and the other GCC countries canceled the work visas of over a million Yemenis. The loss of income from remittances dealt the Yemeni economy a blow it never really recovered from.

After September 11 and the advent of the “War on Terror,” Saudi Arabia and the United States dramatically increased aid to Yemen. The threat of Yemen becoming a base from which Salafi inspired militants could launch attacks into Saudi Arabia, motivated Saudi officials to adopt a more proactive and overt foreign policy.

Buying Influence

Saudi Arabia has long pursued a policy that aims to secure influence by paying “salaries” to many of Yemen’s most powerful figures within the government, the military and among the tribal leaders. The policy of buying influence has yielded mixed and admittedly largely unquantifiable results, but it forms the backbone of Saudi foreign policy in Yemen. However, it is not just tribal figures that receive Saudi money; it is likely that many ranking members of the Saleh regime receive “salaries” from Saudi Arabia. In a country that is as poor as Yemen, the money provided by Saudi Arabia, especially to lesser figures, is important and gives the Saudis considerably more influence than most other external powers.

The Houthi Threat

In 2009, the Yemeni military’s inability to put down or even contain the Houthi (Muslims who subscribe to a strident form of Zaidi Shi’ism) rebellion in the north forced Saudi Arabia to become directly involved in Yemen (see Terrorism Monitor, January 28, 2010). Saudi Arabia is historically cautious about deploying any of its military assets abroad.

The 1934 war with Yemen and the two Gulf Wars were the only times in more than eighty years that it deployed troops in significant numbers outside its borders, though Saudi troops are currently deployed in Bahrain as part of a Gulf Cooperation Council force. Thus Saudi Arabia’s involvement in the Houthi conflict, though still limited, denotes how seriously they take the threat posed by the Houthis.

Saudi fears of the Houthi movement center on concerns about its own religious minorities in the provinces that border northwest Yemen, where the Houthis are based. The province of Najran in particular is home to a large population of Zaidis and Ismailis (another Shi’a sect). In 2000, Saudi Arabia was forced to put down an Ismaili revolt. Many of the residents in Najran are also ethnically Yemeni.

The 2009-10 phase of the Houthi war left the Houthis in control of large parts of the Yemeni governorate of Sa’dah, which abuts the southern border of Saudi Arabia. The signs are that the Houthis and Houthi aligned groups are already taking advantage of the weakness of the Saleh regime by consolidating their hold on the region. In particular, reports indicate that they have taken complete control of the city of Sa’dah (Mareb Press, March 21; NewsYemen March 20). These events must have the Saudis deeply worried, although, given the poor performance of their forces against the Houthis in 2009-2010, it is unlikely that they will take any kind of overt action apart from continuing to try to shore up defenses and security along their southwestern border.

Saving President Saleh?

Saudi Arabia, like other regional powers, is scrambling to try to assess, manage, and, if possible, contain the rapid rate of political change in the region. Saudi Arabia’s management of its foreign policy in Yemen has been frustrated by its own internal divides. The Yemen portfolio, in theory, belongs to Crown Prince and Defense Minister Sultan bin Abd al-Aziz al-Saud. However, he is ill and possibly incapacitated. Interior Minister Prince Nayef Abd al-Aziz al-Saud and his son Prince Muhammad bin Nayef seem to be the men who are really in charge of the portfolio but this remains unclear.

Outwardly, Saudi Arabia has continued to pursue its usual conservative and cautious approach to foreign policy by largely refusing to comment on events in Yemen. However, subtle shifts are detectable. The Saudi supported satellite channel al-Arabiya, while largely ignoring the revolt in Bahrain, has been covering Yemen and has used introductions like “Change in Yemen.” Despite an at times contentious relationship with President Saleh, the Saudis cannot in anyway be happy about his likely departure and what this will mean for Yemen. Keeping Yemen weak and divided was very much an historical objective of Saudi foreign policy in Yemen, but the possibility of having a fragmented and chaotic Yemen as a neighbor at a time when Saudi Arabia is already facing its own set of problems likely means that Saudi Arabia is doing all it can to encourage stability and some kind of orderly transition that ensures roles for as many members of the Saleh regime as possible.

Conclusion

One analyst recently speculated that if Yemen were to descend into civil war, a real possibility would be that as much as half of Yemen’s population of almost 24 million might try to seek shelter in Saudi Arabia. [3] Saudi Arabia could not begin to manage this. It largely failed to manage the refugee/ IDP crisis that arose from the 2009-10 war with the Houthis. Saudi Arabia’s cautious and almost always covert foreign policy of the past may well be replaced with one that is more overt. This kind of change would be replete with dangers. Saudi Arabia is not popular with large portions of the Yemeni populace. Its involvement in the 2009-10 war against the Houthis helped further erode Saudi popularity in the country. Yet the changes in Yemen could easily – and most likely will – affect the House of Saud. In this regard, the possibly prophetic last words of King Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud are certainly worth remembering.

Note:

1. Christopher Van Hollen, “North Yemen: A Dangerous Pentagonal Game,” Washington Quarterly 5(3), 1982, p.137.

2. See, F. Gregory Gause, Saudi -Yemeni Relations, Colombia University Press, 1990.

3. https://csis.org/files/attachments/100302_gulf_roundtable_summary.pdf.

Michael Horton is a Senior Analyst for Arabian Affairs at The Jamestown Foundation where he specializes on Yemen and the Horn of Africa. He also writes for Jane’s Intelligence Review, Intelligence Digest, Islamic Affairs Analyst, and the Christian Science Monitor. Mr. Horton studied Middle East History and Economics at the American University of Cairo and Arabic at the Center for Arabic Language and Eastern Studies in Yemen. Michael frequently travels to Yemen, Ethiopia, and Somalia.