Time Running out for Ukraine to Meet EU’s Association Criteria

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 62

By:

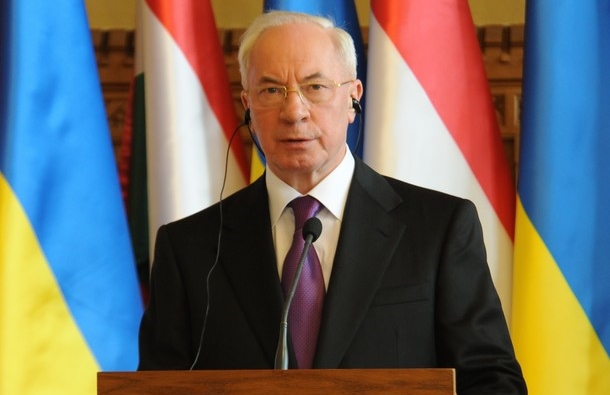

Both the European Union and Ukraine will lose if an association agreement is not signed this year, but European politicians would rather have Ukraine bear the responsibility for such a failure, Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov said on his recent visit to Hungary (kmu.gov.ua, March 28). The Ukrainian leadership is trying to shift the blame on the EU for the possible failure to sign the agreement, as it is clear at this point that Kyiv will not meet Brussels’ conditions this year. Therefore, much will depend on the Europeans’ political will. If the EU, as Kyiv apparently hopes, turns a blind eye to Ukraine’s failure to reform itself, the agreement will be signed.

The Association Agreement (AA) and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) between the EU and Ukraine were technically ready for signing last year, but the EU did not hurry to do so, mainly in protest against the imprisonment of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko and former Interior Minister Yury Lutsenko, whom the EU believes are victims of selective justice. It was agreed at the Ukraine-EU summit on February 25 that the deal would be signed during or before the EU Neighborhood summit scheduled for November 2013, if Ukraine showed progress in judicial, electoral and other reforms by May (Ukrainska Pravda, February 26).

EU Ambassador to Ukraine Jan Tombinski explained after the February summit that Europe understands it would be unrealistic to expect Ukraine to meet all the conditions by May. Kyiv has to show at least some progress—in particular start reforming its prosecution and courts, which notoriously lack independence. Tombinski also said the EU expected Ukraine to free Lutsenko (TVi, February 28). Apparently Brussels is no longer insisting that the other imprisoned opposition leader, Tymoshenko, who faces new charges of involvement in murder in the mid-1990s, should be freed soon. Ukrainian Justice Minister Oleksandr Lavrynovych also said that by May Ukraine has to show “will, decisive actions and progress in certain directions,” and that there was no requirement for Ukraine to complete any particular reform by May (UT1, February 28).

However, time is running out for Ukraine to accomplish even as little as is required by the EU. President Viktor Yanukovych has reacted to Brussels’ prerequisites slowly and in a bureaucratic manner, issuing a decree more than two weeks after the summit, instructing the government to take measures to meet the conditions—in particular, to inform the EU each month about Ukraine’s progress, approve the acts necessary for visa regime liberalization by the EU, improve Ukrainian electoral legislation, finance activities for implementing legal reforms, organize repeat elections in those constituencies where the results of the October 2012 election were invalidated, speed up reforms in the energy sector, and launch a dialogue on Ukraine’s business climate with the EU (Interfax-Ukraine, March 13; Kommersant-Ukraine, March 14).

This is not enough. And in practical terms, Ukraine has not done anything in over a month since the summit. The Ukrainian government lacks a clear strategy for reform. It has been implementing selected recommendations from the EU, Russia and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in a haphazard manner, Tombinski said most recently. He warned that the AA signing, if it did not take place this year, would be postponed indefinitely because of elections in the EU in 2014 and the presidential election in Ukraine in 2015 (Interfax-Ukraine, March 19). Not only Yanukovych and his government are to blame for this, but also the opposition; for long periods during the past several months, the opposition boycotted the legislature, which has to pass several laws promised to the EU.

In the meantime, Brussels has issued another warning—in the form of an EU neighborhood package report—that time is running out for Kyiv. While acknowledging that Ukraine took some steps toward legal and judicial reforms and adopted laws on asylum and refugees, the report said Ukraine had failed to act on most of the recommendations contained in last year’s report. The EU noted that Ukraine still has to tackle shortcomings in its electoral system, address the problem of selective justice, step up its fight against corruption, reverse the backsliding that occurred recently in public procurements and budget transparency, establish a macroeconomic framework for the IMF to issue new loans, as well as refrain from protectionist measures (Kommersant-Ukraine, March 21).

The Ukrainian foreign ministry only provided a bureaucratic response to the EU’s criticism. The government, the ministry said, carried out its own one-year plan for European integration consisting of 71 measures. According to Ukraine’s own timetable, it has implemented six integration measures, and several of these were put into effect ahead of schedule (Channel 5, March 20). One positive development for the time being is that Kyiv has somewhat clarified its choice between the EU and the Russian-led Customs Union. Despite Russia’s pressure to join and promises of cheap gas, Yanukovych told a press conference after the Ukraine-EU summit that Ukraine could become no more than an associate member of the Customs Union (UT1, March 1). Azarov confirmed two weeks ago that Ukraine had been in talks to attain associate membership in the Customs Union, but was not seeking any privileges or preferences (Ukrainska Pravda, March 19). Though still a hedge, these statements point to Kyiv’s ultimate preference for European, rather than Eurasian, integration. Yet, Ukraine’s political will to actually achieve the former still remains an open question.