Turkish-Greek Relations in the Aegean: Is a Solution Possible?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 43

By:

Turkish-Greek negotiations over the delimitation of their maritime zones in the Aegean Sea have persisted for decades. But the dispute spilled out into the wider Eastern Mediterranean after the discovery of large hydrocarbon resources there and efforts by other actors to solidify their own offshore claims. Greece and Turkey stand on opposite sides of this rivalry, notwithstanding both countries’ membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). And the collision of Greek and Turkish warships in August 2020, amidst maritime delimitation works, quintessentially illustrated the risk of escalation that presently exists between the two treaty allies (Cumhuriyet, August 14, 2020). Muscle flexing continues in the region via military maneuvers. In February, the Hellenic Airforce conducted drills in the Aegean with the participation of 29 aircraft (Ekathimerini, February 24); whereas, between February 25 and March 7, Turkey conducted the Blue Homeland exercise, involving 87 ships, 27 airplanes and 20 helicopters (TNF, February 22).

In January 2021, after a five-year break, both parties resumed exploratory talks to find a solution to their unresolved maritime problems (Balkan Insight, February 25). Although the issue could be brought before the International Court of Justice for legal adjudication, Ankara and Athens have sought to resolve their bilateral disputes politically since the 1970s. The delimitation of their air and maritime zones are part of the problem from Turkey’s perspective. Ankara posits that because the Aegean is a semi-enclosed sea with the presence of thousands of islands, there is a need to find a solution that is agreeable to both parties. However, Greece perceives such as stance as a challenge to its sovereignty and opts to limit the negotiations agenda to solely the delimitation of the continental shelf in the Aegean (Mfa.gr, accessed March 16).

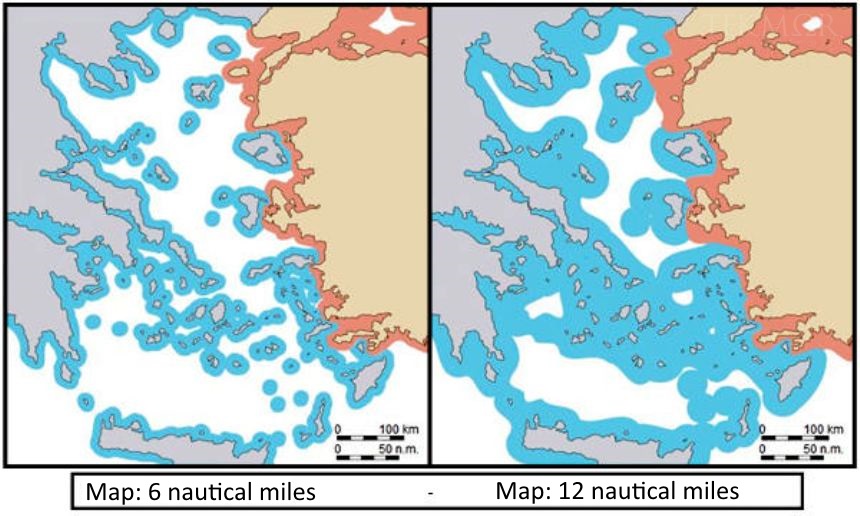

The modern-day borderlines between Greece and Turkey were drawn up in 1923, with the Treaty of Lausanne, which extended their territorial waters out to three nautical miles. Greece changed this to six nautical miles in 1936. At that time, Ankara was focused on preserving good relations with Athens as the co-signatories of the Balkan Entente, and so it did not protest the Greek decision. But later, Greece unveiled its intention to increase its territorial waters even further, to 12 nautical miles. For Turkey, one of the main concerns is that Greece controls thousands of islands in the Aegean, some of which lie just 3–4 miles from the Turkish coastline. So were Greece to enforce the 12-mile territorial sea claim, including around each of its island possessions, 63.9 percent of the Aegean would be under Greek control. This would make navigation for Turkish vessels in the Aegean impossible without having to pass through Greek waters. As a response, in 1995, the Turkish parliament declared that any potential extension of territorial waters in the Aegean to 12 nautical miles would be a casus belli.

The ongoing dispute over maritime borders is also linked to a debate over airspace use. Greece claims a ten-mile air zone of sovereignty surrounding its coast, but Turkey insists this should be limited to six miles, as in the case of territorial waters. The disagreement routinely leads to dangerous aerial incidents over the Aegean Sea, which in turn fuel a bilateral arms race. The two parties directly signal one another by sending fighter jets on overflights of “gray” (disputed) areas, triggering aerial interceptions (though usually unarmed) by the other side. Nonetheless, one such aggressive interception culminated in a collision of two jets in the sky in 2006 and the death of the Greek pilot (Hurriyet, May 23, 2006).

In addition to pushing for a six-nautical-mile limit in both the sea and sky, Ankara also demands that all the islands in the eastern Aegean should be demilitarized; whereas, Greece continues to fortify these isles. Moreover, former secretary general of the Turkish Ministry of Defense, Ümit Yalım, has stated on different occasions that Greece has also occupied islands that were supposed to belong to Turkey and militarized them (Sputnik, January 23, 2020). The Lausanne and Paris (1947) treaties define a demilitarized status for the Dodecanese Islands. However, since 1923, primarily Italy and then the Hellenic Republic deployed military assets there. Mutual militarization of the eastern Aegean ramped up particularly following Turkey’s intervention in Cyprus, in 1974.

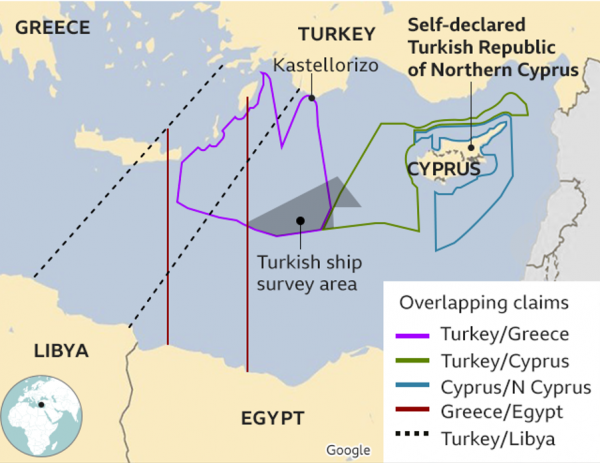

The parties have engaged in unending diplomatic talks for decades, but the delimitation problems remain unresolved. And now, these same problems have been spreading to the Eastern Mediterranean. Kastellorizzo (officially Megisti) is one of the Dodecanese islands that Italy transferred to Greece as reparations following World War II. The small island is located 2.1 kilometers (just over 1 nautical mile) off the southern coast of Turkey and has been a main topic on Ankara’s foreign policy agenda since negotiations over the Lausanne treaty. Greece claims an extended maritime border by arguing that this island has a right to its own continental shelf, which would effectively squeeze Turkey into the Gulf of Antalya. Rejecting the Greek assertion, Turkey states that the island’s distance of several hundred kilometers from the Greek mainland means that Kastellorizzo can only have territorial waters. Indeed, Turkey dispatched its seismic vessel Oruç Reis and a naval escort to the disputed area to demonstrate that the given geography falls within Turkey’s own continental shelf. Greece followed suit, and tensions escalated in 2020. Moreover, that same year, Ankara signed a maritime delimitation agreement with the Tripoli government in Libya, and Athens did with Cairo.

De-escalation came in December 2020, when Brussels postponed discussions of a possible European sanctions package against Turkey to March 2021 and paused to coordinate its response with the incoming Joseph Biden administration in Washington. Ankara, in turn, restarted negotiations with Athens that January. Both parties are now looking for possible diplomatic maneuvers by cooperating with third parties even as they resume bilateral exploratory talks. From Ankara’s perspective, an opening with Cairo could be game changer. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, in a recent statement, said that, depending on the course of events, Turkey could sign a maritime border agreement with Egypt (Milliyet, March 3). Cairo’s rejection, in November, of the Greek continental shelf argument involving Kastellorizzo as well as its decision not to provide hydrocarbon tenders in disputed waters were both seen as positive signals by Ankara (Anadolu Agency, March 3). The normalization of Turkish-Egyptian ties would create new momentum in the region. Yet some caution is warranted: Turkish officials notably expressed similar statements earlier last year, which ended with an agreement between Athens and Cairo. One way or another, however, developments beyond the Aegean Sea increasingly shape bilateral affairs between Greece and Turkey.