Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan Confirm New Supply Routes

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan Confirm New Supply Routes

On February 24 and 25 Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdimukhamedov paid a state visit to Uzbekistan for talks with President Islom Karimov. The discussions, which covered a wide range of issues, signaled a further strengthening of bilateral ties; but this was overshadowed by the confirmation by both leaders that their countries would participate in the northern supply route, assisting in the delivery of non-lethal materials to Afghanistan (Uzbek National News Agency, February 25). This is a further indication that the security dynamics in the region are rapidly changing following Russia’s recent moves to undermine the U.S. military presence at Manas and activate the CSTO Rapid Reaction Forces. U.S. and NATO planning staffs are evidently engaged in a search for viable options to ensure continued supplies for the forces in Afghanistan.

Karimov confirmed that Uzbekistan would allow access to the country for the transit of nonmilitary cargo into Afghanistan. "Uzbekistan has agreed to transit nonmilitary cargo into Afghanistan, if its legislative norms are abided by," Karimov said following talks with the Turkmen president. The significance of transiting cargo through Uzbekistan into Afghanistan cannot be overstated, since the country is located strategically within the region. All cargo sent to Afghanistan using the northern supply route will pass through Uzbekistan. Karimov also noted that his country currently supplied Afghanistan with electricity, and he appeared to show an interest in reactivating the construction of the Termez-Mazar-e Sharif railway, which would link Termez to Afghanistan (Uzbek Television First Channel, February 25).

Despite Turkmenistan’s neutrality, Berdimukhamedov also agreed to open Turkmen airspace for the transit of nonmilitary cargo in support of the ISAF’s mission in Afghanistan. "We have nothing against the transit of humanitarian aid via our air corridor," he said. It is interesting that he should announce this in the context of his visit to Tashkent. This underscores the increasingly important bilateral relationship between Ashgabat and Tashkent and also implies that Berdimukhamedov may be looking to Karimov for guidance in handling Turkmenistan’s relations with the West. This may fit Ashgabat’s cautious approach, as it observes the slow restoration and evolution of Tashkent’s relations with the U.S. and NATO, following the troubled period after May 2005 (Interfax, February 25).

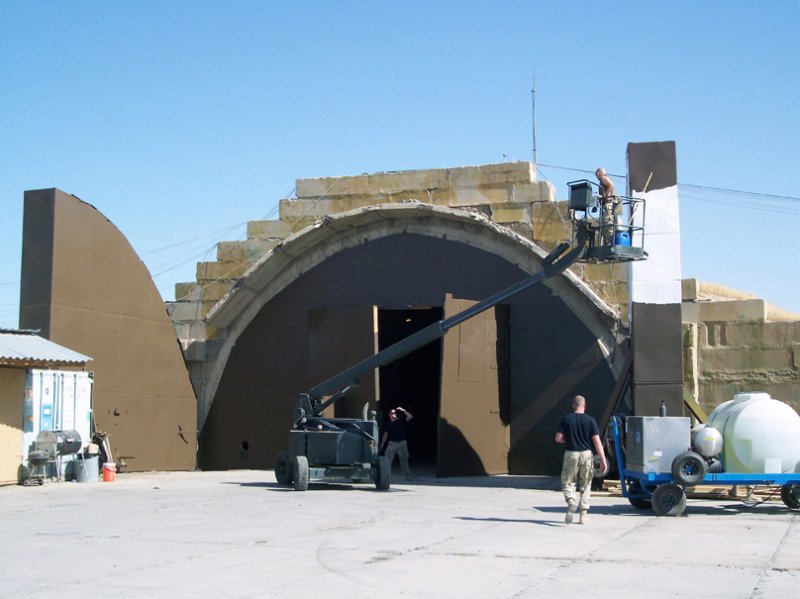

The use of an air corridor through Turkmenistan raises the question of where the shipments would originate from. There may be an effort to provide additional options to the six-day, overland northern route, which begins in Latvia and crosses Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. Diverting supplies from Uzbekistan through Tajikistan could help avoid a bottleneck at Termez. The first test consignments in the northern route began in Latvia on February 19 and arrived in Uzbek territory on February 25. The use of Turkmen airspace makes sense if NATO supply flights can either depart in the future from Turkey, through Iranian and Turkmen airspace, or from Navoiy or Karshi-Khanabad in Uzbekistan, again through Turkmenistan. One senior NATO general has already mooted the idea of opening a discussion on transit with Tehran (www.nationalreview.com/02/05/<wbr></wbr>2009).

Naturally, the transit agreements reached with Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have been downplayed in Moscow. Andrey Grozin, head of the Central Asian department of the Institute of CIS Countries, does not consider this development a geopolitical "threat" to Russia’s interests in the region. "There is nothing unexpected in the fact that Ashgabat and Tashkent agreed to allow cargo for the coalition forces in Afghanistan to transit through their territories. This is in line with what the leaders of these two countries have said about the fight against terrorism and is also quite understandable in view of the financial crisis. They will receive money for the transit," Grozin explained (Interfax, February 25). However, as Moscow asserts its foreign policy more aggressively within Central Asia, it will notice that the United States and NATO are reconfiguring their security interests within the region. Given the poor track record of bilateral cooperation among the Central Asian states, the deepening ties between Ashgabat and Tashkent are arguably becoming the most active partnership within the region.

The real significance of the meeting in Tashkent went beyond the transit agreements. Karimov and Berdimukhamedov also signed a number of significant cooperation documents, not only showing the extent of their bilateral partnership but creating the framework for closer security cooperation. These included mutual extradition agreements; measures to jointly combat transnational crime; border security agreements involving cooperation between border guards at Uzbek-Turkmen checkpoints; a protocol on cooperation between Uzbekistan’s National Security Service (SNB) and the State Border Service of Turkmenistan relating to searches; and a protocol between the SNB and the Turkmen Ministry of National Security on mutual assistance and cooperation (Uzbek Radio, February 25).

Their talks also covered water resources management, energy, tourism, regional security, and, of course, Afghanistan. Both sides expressed a "commonality" on the positions they held on key subjects. Berdimukhamedov stated:

I would like to note the constructive nature of our talks held here in a traditional atmosphere of friendship, openness, mutual confidence, and understanding. Our talks once again confirmed the adherence of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan to the steady expansion of [our] partnership, strengthening neighborly relations between the two fraternal nations. I would like to say that we highly appreciate the current state of our dynamically advancing relations with Uzbekistan, based on principles of equality and mutual benefits (Interfax, February 25).

New cooperative arrangements and dynamics are needed in Central Asia, both to promote the stabilization of Afghanistan and strengthen regional security. Finding ways of achieving this in a way that bypasses Russian paranoia over American bases in the region will not only defuse tension with Moscow but facilitate greater practical input from NATO’s partners in Central Asia. The recalibration of the U.S. security strategy relating to Afghanistan will demand forging new partnerships in Central Asia, with an emphasis on low-key access rather than high profile basing rights.