Waking Up? China Moves on Environmental Issues at Paris Summit

Publication: China Brief Volume: 15 Issue: 24

By:

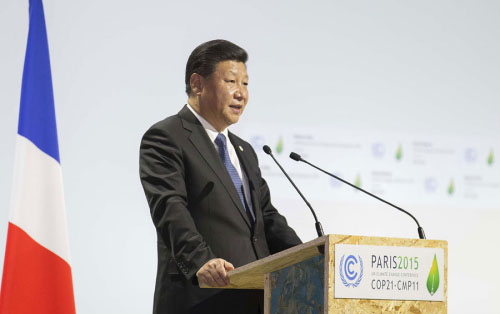

In 2009, the image of Chinese ministers asleep at their desks at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen was taken as a metaphor for the world’s torpid movement on environmental issues. With the results of the recent Paris Conference on Climate Change showing progress and a number of reforms by China’s top leadership, it is becoming clear that, in terms of both foreign and domestic policy, China is “waking up” to face its environmental problems.

At the conference in Paris, which ended on December 12, delegates from 196 countries agreed to a framework that, if approved by a majority of top carbon emitters, will become legally binding. China and the U.S., despite their frequent and ongoing disagreements on a number of strategic issues, are viewed as being cooperative partners in this endeavor.

The groundwork was laid during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Washington in September. U.S. President Obama and President Xi “reaffirm[ed] their shared conviction that climate change is one of the greatest threats facing humanity and that their two countries have a critical role to play in addressing it” (NDRC, September 26). China committed itself to lowering carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP by 60-65 percent from its 2005 level by 2030.

As ever, balancing the needs of economic growth and environmental protection have proven difficult, particularly with a country as reliant on coal for power generation, and whose economy is widely viewed as going through a period of contraction.

Domestically, at the top level, there are positive signs. A White Paper issued by the National Development and Reform Council (NDRC), China’s top economic planning agency, acknowledged a range of environmental crises—from droughts and soil degradation to air pollution, paving the way for further action (NDRC, November 2013). Premier Li Keqiang announced at a June meeting of the body that China was on-track to achieve the current five-year plan’s carbon-reduction and environmental goals (Gov.cn, June 12). The Leading Small Group for Comprehensively Deeping Reforms (中央深改组), a committee lead by Xi Jinping and members of the Politburo Standing Committee, issued a series of action plans dealing with the environment (Xinhua, July 5). Specifically, these reforms within the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) have shifted responsibility onto local cadres to improve and changed the budget mechanism for local environmental bureaus’ (环保局) that had discouraged them from issuing fines. The MEP’s new media savvy “scholar-politician” Chen Jining has been a much more effective voice than his predecessors (China Brief, December 7). While these moves at the highest level are certainly welcome, facts on the ground paint a different picture.

At the local level, things are less encouraging. China has for many years seen large protests against specific environmental threats, particularly carcinogenic chemical-producing factories. Though these groups have been effective in shutting down polluting factories in Xiamen and Dalian, cities in China’s south and north, similar protests elsewhere, including in Kunming and Chengdu, both cities in China’s south west, have faced more stern opposition from local governments (SCMP, May 20, 2013). In response to mass protests, the Kunming city government eventually published an environmental report on the proposed factory (Beijing Morning Post, June 26, 2013). In each of these cases, government action came only after it became apparent that media suppression and riot control would no longer be effective. Moreover, government action was successful in suppressing these issues from becoming larger, national level movements.

More troublingly, seemingly universal problems, such as urban smog, have failed to mobilize significant protest. Years after the U.S. Embassy briefly labeled Beijing’s air as “crazy bad,” this month, Beijing issued its first ever smog red alert (ChinaNews Online, December 7; Caixin, December 8). This was quickly followed by a second red alert less than two weeks later (Sina Online, December 18). It appears that most Chinese citizens have chosen to simply don their breathing mask, change the filter of their air purifier and get on with their lives.

The Chinese government, through its restriction of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), lack of support for grassroots environmental efforts and long inattention to environmental issues that could slow economic growth has created a recursive loop of focus on growth, empty promises and apathy. Though China’s cooperation in international forums is certainly welcome, without a “comprehensively deep” internalization of environmental protection, from the Politburo to the city block, the needed will to correct China’s environmental issues—much less global concerns—will be lacking.