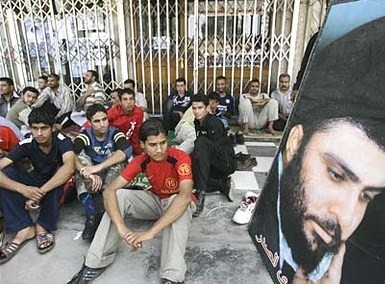

Who Speaks for the Shi’a of Iraq?

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 7

By:

Iraq’s Shi’a Arabs, the demographic majority with an estimated 60-70% of the population, wield the most political influence in Iraq. But the Shi’a of Iraq are a diverse group, with major regional differences between the Shi’a of Basra and the deep South and the Shi’a of the north-central region. Iraq’s Shi’a hold divergent views on the appropriate role of religion in government. Other areas of internal division among Shi’a parties exist, such as a common position on cooperation with the United States, but these are secondary in their influence on Shi’a voters.

Iraq’s Shi’a political parties have fought battles with each other that at times were as bloody as the sectarian war between Sunnis and Shi’a in 2006-2008. From 2005-2008, the Badr Corps of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) and Sadrists fought militia battles in the streets of Basra. In 2009, the two groups reconciled and formed a coalition for the March 2010 elections. How could two groups bent on eliminating each other become allies only two years later? Why did Da’awa—the compromise party supported by both ISCI and Sadrists in 2006 for the Prime Ministership—break from the coalition in 2009?

Secularism vs. Theocracy

Iraq’s Shi’a hold widely divergent views on secularism and the role of religion in post-Saddam Iraq. Many Shi’a view secularism—a main characteristic of Saddam’s regime—with distrust. Indeed, secularism and Ba’athism are synonymous in the minds of many Iraqi Shi’a. Saddam’s Ba’athist agents, both Sunni and Shi’a, noted who attended Shi’a mosques and reported on Shi’a clergy and Iraqi travel to Iran. Saddam was not trying to exterminate Shiism from Iraq. Rather, he wanted to eradicate the Shi’a opposition that used Shi’a religious institutions and sought refuge in Iran to organize and plan attacks against Saddam. But the effect of Saddam’s surveillance of Shi’a mosques and clergy was perceived by Iraq’s Shi’a population as a threat to their religious identity. In spite of opposition to Saddam, many of Iraq’s Shi’a were as secular in their political and social views as most Ba’athists, and opposed an Iranian-style theocratic government.

With the fall of Saddam’s regime and the rise of Iraqi Shi’a political parties, advocacy of an Islamic government became an option, and one that was desired among Shi’a who viewed the incorporation of Shi’a Islam into Iraq’s government as an effective way to render a Ba’athist return to power impossible. Da’awa and ISCI are among those Shi’a parties that espouse an Islamic government in order to protect Shi’a interests in Iraq. These parties rose out of the opposition to Saddam, and their leaders were among the Shi’a opposition targeted by his regime. This religious outlook, however, conflicts with the Shi’a who prefer a secular lifestyle and who do not want to live under an Iranian-style theocratic government. Ayad Allawi’s al-Iraqiya and Ayad Jamal al-Deen’s Ahrar are examples of secular Shi’a parties.

Religious Shi’a parties in Iraq are sometimes assumed to be “Iranian” parties because they share a similar ideology and because of the frequent travel to Iran by religious Shi’a politicians. ISCI in particular has been labeled an “Iranian” party. Contrary to this assumption, some of the most virulent opposition to Iranian influence in Iraq comes from religious Shi’a parties, including ISCI. [1] Iran provided shelter to Shi’a resistance fighters, but these Shi’a Arabs were not treated as equals by Iran and were denied residential rights (Azzaman, January 27, 2009). Arabic remained their primary language, and they returned to Iraq at the first opportunity. Secular Shi’a parties, such as al-Iraqiya, on the other hand, tend to espouse good relations with Iran and shy away from strong criticism of their eastern neighbor (Asharq al-Awsat, January 20).

A great deal of religious rivalry exists between Iraq and Iran. Both Najaf (Iraq) and Qum (Iran) are seats of Shi’a religious power. Religious Shi’a parties distrust Iran’s motives for interfering in Iraqi affairs, and are particularly suspicious of Iran’s interest in Najaf. Secular Shi’a parties, on the other hand, tend to focus on Iran’s potential as a trading partner and how to divide natural resources such as oil and water. When viewed in this manner, anomalies such as the secular anti-Iranian Ahrar party become more comprehensible, in that Ayad Jamal alDeen, a Najaf cleric is both skeptical of Iran’s motives in Iraq and committed to secularist government.

Rivalry between the major Iraqi Shi’a religious parties is understandable, given that the prize would ultimately be power and influence in a future theocratic government. The Badr/Sadr battles of 2005-2007 were not surprising as these two factions have been vying for dominance within the religious Shi’a movement in Iraq. Their rapprochement in 2009 makes ideological sense in that both parties believe a Shi’a theocratic government would best protect Shi’a interests against a possible return of a hostile Sunni dictatorship.

However, further schisms between ISCI and the Sadr movement are very likely because both desire dominance over the theocratic movement in Iraq but draw on different voter bases. [2] In the run-up to the March 2010 parliamentary election, arguments between the ISCI and Sadrist coalition partners drew attention to the fragility of the partnership, with Muqtada Al-Sadr accusing ISCI of sympathizing with the Ba’athists (Aswat al-Iraq, January 22).

De-Ba’athification Masks De-Secularization

The Shi’a are divided on the “de-Ba’athification” of Iraqi politics. With secularism confused with Ba’athism, selective de-Ba’athification would accomplish the religious Shi’a parties’ goals of de-secularization. Some former Ba’athists may be allowed to continue to participate in Iraqi politics as long as they espouse theocratic views. [3] Secularist Shi’a, on the other hand, sometimes wax nostalgic about the Saddamist era, not because they miss Ba’athism, but because they prefer secularism to the imposition of religious dictates on personal lifestyles. Secular Shi’a parties advocate for reconciliation with former Ba’athists and reintegration of Sunni extremists into the government in the name of political stability, but these populations would also temper the influence of the more religious Shi’a parties in government (Al-Bawaba, January 28).

Many Iraqi Shi’a hold both positions simultaneously; they desire a secular government and wish to prevent the return of a Ba’athist government. Shi’a voters will cast their ballots according to which priority is higher at election time. A secular Shi’a voter may prefer Ayad Allawi’s secularist platform but may vote for a religious party if the primary concern is preventing a return of the Ba’athists.

South vs. North Iraqi Shi’a

Iraqi Shi’a of the North/Central region differ from the Shi’a of the South, culturally and linguistically. [4] Southern Shi’a, originating from Nasiriyah, Amara, and Basra, feel entitled to a greater share of political power and resources considering their numerical strength in the most oil-rich region of the country. [5] The Fadilah Party, for example, is a Southern Shi’a party with a stronghold in Basra. Fadilah is a religious party and part of the Iraqi National Alliance (INA) of Shi’a religious parties. But while it is an INA member, Fadilah at times differs from ISCI and Sadrists on issues that pertain to the Southern Shi’a, particularly concerning oil and decentralization (Aswat al-Iraq, November 16, 2009).

Shi’a party positions on decentralization strongly correlate to the geographic base of the respective party’s power. Southern Shi’a favor decentralization, which would result in more revenue remaining in the oil-rich southern provinces. Fadillah, for example, held a referendum in 2008 to declare Basra its own region, but failed to garner the necessary ten percent support to be brought to Parliament. Fadilah’s position is not shared by nationalist Shi’a parties with strongholds outside the deep South because they would suffer if a greater share of resources were diverted to Basra. ISCI also supports decentralization, albeit a larger Shi’a region. Sadrists and Da’awa favor a strong central government that would keep revenue flowing to Baghdad, where both parties historically maintained stronger voter influence.

One of the trends to watch in the Shi’a political landscape will be the “migration” of Shi’a politics southward. In the January 2009 provincial elections, Da’awa came to power in the Basra provincial council. The Fadillah governor was replaced with a Da’awa member. Subsequently, Da’awa began moving away from its strongly centrist position and toward greater regional resource sharing, as reflected in the 2010 budget that accords the Basra provincial government a dollar per barrel of oil produced, a move that puts Da’awa more at odds with centralists but is more representative of the interests of Shi’a in Basra. [6] If Da’awa can maintain a strong power base in Basra, it may not need to ally with the “nationalist” INA to maintain primacy among the religious Shi’a parties. [7]

As Iraq’s population becomes increasingly divided along sectarian lines, a natural occurrence will be the migration of the Shi’a voter base southward. The Basra, Maysan, and Dhi Qar regions likely will gain in power and influence within Shi’a parties because these regions will become almost entirely Shi’a. A strong centralist political line will lose voters in the South. As internal displacement along sectarian lines continues and the country itself becomes more divided, decentralization is a more likely outcome.

[See Above Table for Reference]

Notes:

1. “Shiite Politics in Iraq: The Role of the Supreme Council,” International Crisis Group. Middle East Report No.70, November 15, 2007.

2. Reidar Visser, “Sadr-Badr Compromise in Tehran, the Iraqi National Alliance (INA) is Declared,” www.historiae.org, August 24, 2009. The ISCI voter base draws on upper and middle class, well-educated, middle aged Shi’a. The Sadrist voter base is younger, under-employed and less educated. See “Shiite politics in Iraq: The Role of the Supreme Council,” International Crisis Group: Middle East Report No. 70, November 15, 2007.

3. Reidar Visser, “Some More De-Baathification Metrics,” Iraq and Gulf Analysis, January 22, 2010. See also Reidar Visser,. “The 511 De-Baathification cases: Sectarianism or Despotism?” historiae.org, January 20, 2010.

4. Reidar Visser,. “Basra, the Reluctant Seat of ‘Shiastan’?” Middle East Report. March 12, 2007.

5. Reidar Visser,. “Decentralization Bonanza in the Iraqi Budget.” .historiae.org, .January 27, 2010.

6. Ibid

7. Reidar Visser, “After Sadr-Badr Compromise in Tehran, the Iraqi National Alliance (INA) is Declared,” historiae.org, August 24, 2009.