WHY DID PUTIN COME TO MINSK?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 4 Issue: 236

By:

On December 13-15, Russian President Vladimir Putin made the first official visit to Belarus of his presidency, which is scheduled to end on March 2, 2008, when new presidential elections take place in Russia. Ostensibly, the visit concerned the next stage of development of the Union State, and one week prior to the meeting, the Belarusian government acknowledged that talks would focus on a new draft constitution. However, despite the secrecy surrounding the meeting, the Union State was not the main reason behind the talks.

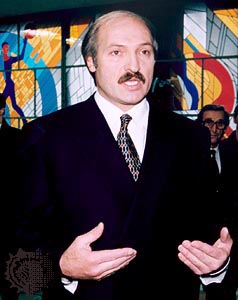

Prior to the meeting speculation was rife among the Russian media that Putin intended to coerce Belarusian president Alyaksandr Lukashenka into forming a Union State that would effectively end Belarusian independence and provide Putin with a new political career as the head of the new entity, which theoretically could wield greater power than the Russian state alone under a new president. Demonstrations held by members of the opposition to protest Putin’s visit and defend Belarusian sovereignty resulted in some of the harshest military actions since the 2006 presidential elections, including the beating of United Civic Party leader Anatol Lyabedzka and the hospitalization of one youthful demonstrator, plus injuries to dozens of others.

The Russian daily Kommersant also questioned Putin’s initial meeting at the airport with Belarusian Prime Minister Syarhey Sidorsky, which journalist Andrei Kolesnikov considered a breach of protocol and an affront to Lukashenka. However, of more importance is why Putin chose this particular time to visit Minsk. The two presidents had a private meeting that lasted four hours, and even the official government organ SB Belarus’ Segodnya acknowledged ruefully that other than the official handshake between the two leaders, it had little knowledge about the contents of the discussion.

Subsequently there were broader meetings that included high-level officials from both sides. The Russian delegation included Prime Minister Vladimir Zubkov; Sergei Mironov, chairman of the Council of the Federation; Boris Gryzlov, speaker of the State Duma; and Minister of Finance Alexei Kudrin. Notably absent was Putin’s nominee for president, Dmitry Medvedev, and Pavel Borodin, the State Secretary and informal head of the Union State. The two sides reportedly discussed means to consolidate economic, political, and military ties.

On the economic front, Belarus has agreed to adhere to the regimen applied last year for gas imports and will pay prices that are 67% of Western European levels. In return, Russia has agreed to a loan of $1.5 billion to offset the higher prices. The signing of the loan was something of a breakthrough for the Belarusians, and it is worth noting that Belarus will still pay prices for gas that are well below the levels paid by Georgia and Ukraine. Debating the reasons for Putin’s visit, Alyaksandr Milinkevich, head of the Movement for Freedom, commented that the macro-economic stability of Belarus had become dependent on support from Russia, and specifically the leadership in Moscow. Such a situation is contrary to the national interests of Belarus, in his view.

But given the lack of news on the Union State – Putin’s decision to accept the post of prime minister when he steps down in March effectively destroys the notion of his heading such a state – and the lack of change on the gas issue, then the real point of the meeting was likely to debate military and security questions. In late August, Alexander Surikov, Russian ambassador in Minsk, stated that Russia was prepared to deploy new military facilities in Belarus, including tactical nuclear weapons. One report noted that Belarus has kept its missile launchers in prime condition should the weapons given up in the mid-1990s ever be returned from Russia. Russia, in other words might have been seeking confirmation from Belarus that it would remain a partner in the campaign to oppose U.S. plans to build missile-defense facilities in Poland and the Czech Republic.

If so, then its quest was successful. Lukashenka reiterated his commitment to Russia as a military ally, commenting that Belarus would stop “tanks advancing to Moscow.” The two leaders had a symbolic visit to Victory Square, and Putin recollected the common history of the two countries as well as the open border and the fact that Russians are “not foreigners” in Belarus. Belarus currently is home to the Volga radar station in Hantsavichi (Brest region), part of its early warning system, as well as a long-range radar center in Vileyka, west of Minsk. The latter station maintains contact with Russian nuclear submarines in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans (and part of the Pacific Ocean), and Belarus has never seriously considered removing them.

Although Lukashenka has defended Belarusian sovereignty and had a war of words with Putin in recent months, he has remained fearful of NATO’s advances into Eastern Europe. The Americans have opted to raise sanctions against the Minsk government and have condemned the recent crackdown on demonstrators. Therefore Belarusian leaders are happy to agree to Putin’s latest request. Presumably the Russian president is ensuring that his western border is secure before taking the next step after the suspension of adherence to the Conventional Forces in Europe treaty. For Belarus, official defiance toward Russian threats to its sovereignty and the imposition of high gas prices appears to have dissipated in the face of a much larger potential peril.

(Belorusy i rynok, December 17-24; Belorusskaya delovaya gazeta, December 17; SB Belarus’ Segodnya, December 15; Kommersant, August 28, December 15; www.charter97.org, December 13; BBC News, December 14)