Iran’s Red Sea Strategy Amid the RSF–SAF Fratricidal War in Sudan

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 22 Issue: 11

By:

Executive Summary:

- Iran is supplying the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) of General Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan with drones and other weaponry in its struggle against the rebel Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by General Hamdan Daglo “Hemedti.” This has given rise to concerns that Tehran desires to establish a naval facility in Sudan.

- In combination with the Iran-friendly Houthi movement in Yemen, such a base would offer a point from which Iran could further threaten Red Sea shipping as well as the main maritime entry point for Muslims making the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.

- Iran–Sudan relations have fluctuated over the last several decades, especially since the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir. In particular, tensions stemming from Sudan’s Sunni-majority population and Iran’s promotion of Shi’ism tend to place a limit on Tehran–Khartoum ties.

- Despite official denials, Iran is suspected of either attempting to establish a naval facility on Sudan’s Red Sea coast or gain access to preexisting ports there given the strategic advantages offered by doing so. Doing so may represent a bridge too far for U.S.–Sudan relations, which Khartoum has spent years working to improve.

A supporter of the Palestinian cause since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran has adopted an aggressive stance in response to Israel’s offensive on Gaza. As part of a strategy to assert itself regionally, Tehran has taken advantage of its proximity to the Red Sea, one of the world’s most important trade conduits, to apply pressure on Israel and its Western backers. With the Iran-friendly Houthi movement in Yemen installed near the narrow Bab al-Mandab Strait at the southern end of the Red Sea, Iran is taking a new interest in Sudan and its 465-mile Red Sea coastline. To this end, Tehran is supplying the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) of General Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan with potentially game-changing weaponry in its struggle against the rebel Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by General Hamdan Daglo “Hemedti.” This raises two questions: What does Tehran want in return? And is it likely to get it?

Sudan’s Relations With Iran

In the 1990s, Iran enjoyed a close relationship with the Islamist military regime of President Omar al-Bashir. He welcomed Iranian technical and diplomatic support in his effort to create a more Islamic state and defeat South Sudanese separatists. Many of the Islamists who were ejected from power after al-Bashir’s overthrow in 2019 now support General al-Burhan’s SAF.

Relations with Iran were cut in January 2016 when Khartoum sided with Saudi Arabia after a mob attacked the Saudi embassy in Tehran in reaction to the execution of top Saudi Shi’ite cleric Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr and 46 others on January 2, 2016 (Press TV [Tehran], February 5). Al-Bashir’s government then turned to Iran’s Arab rivals in the Gulf states for support. During this time, Sudanese troops (mostly RSF) fought alongside Saudi forces against the Iranian-backed Houthi movement in Yemen.

The centuries-old Sunni–Shi’ite religious divide complicates relations between Sunni Sudan and Shi’ite Iran. After al-Bashir downgraded relations with Iran in 2014, he made it clear the move was made in reaction to alleged attempts by Iranian diplomats to spread Shi’ism in Sudan: “We do not know Shi’ite Islam. We are Sunnis. We have enough problems and conflicts and we do not accept introducing a new element of conflict in Sudanese society” (Sudan Tribune, January 31, 2016).

A March 2023 Saudi–Iranian rapprochement brokered by Beijing allowed Khartoum to make its own move to renew relations with Tehran. The shift was welcomed at the time by Hemedti, who had risen from a minor member of the notorious Janjaweed militia to commander of the RSF paramilitary (X/@Generaldagllo, March 10, 2023). When the renewal of diplomatic relations was made official in October 2023, one of Tehran’s most immediate concerns was Sudan’s growing relationship with Israel through the U.S.-backed Abraham Accords (Sudan Tribune, October 9, 2023).

The Israel Issue in Sudan–Iran Relations

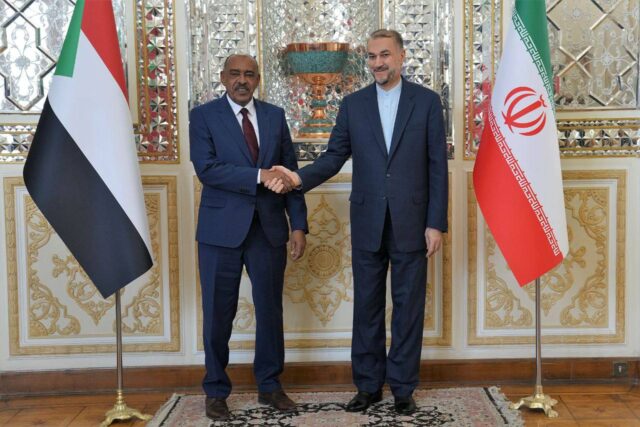

Ali al-Sadiq Ali, Sudan’s acting minister of foreign affairs, met Iran’s late president, Ebrahim Raisi, in Tehran on February 5 to discuss their countries’ improved relationship. During the meeting, Raisi emphasized that the “criminal Zionist regime” could never be a friend to Islamic countries. Without mentioning Sudan by name, he condemned those Islamic nations that chose to pursue normalization of relations with Israel (Mehr News [Tehran], February 5).

Following a law implemented in 1958, Sudanese leaders were forbidden from normalizing relations with Israel. The upheavals that followed the overthrow of President al-Bashir in 2019 provided an opening for the United States to bring Sudan into the Abraham Accords in exchange for a long-desired removal of American sanctions on Sudan. A member of Sudan’s ruling Sovereign Council, Admiral Ibrahim Jaber, rejected suggestions that relations with Iran spelled an end to the Accord, claiming that renewed relations with Iran would not affect diplomatic normalization with Israel: “We will pursue normalization when it benefits us and refrain from it otherwise” (Sudan Tribune, March 24).

On February 2, 2023, Sudan and Israel finalized a deal to normalize relations. Israel hoped the deal would facilitate the deportation of Sudanese asylum seekers, but the outbreak of hostilities in Sudan in mid-April 2023 put further developments in this area on hold (Haaretz, February 3, 2020). If Sudan grows closer to Iran, its commitment to the Abraham Accords—which were half-hearted at best, even before the Gaza offensive—is likely to wither on the vine.

Iran and al-Burhan

Iran’s support for al-Burhan and the SAF is assisted by the Sudanese army’s solidly Islamist officer corps (the result of repeated purges) and the backing of Islamist militias and leaders from the al-Bashir regime connected to the SAF. Despite the Sunni–Shi’a divide, Sudan’s Islamists have a long record of cooperation with Tehran. These ties in the past included Iranian military training for Sudan’s Popular Defense Forces. [1]

In return for arms, Iran will likely demand that Sudan cut its already damaged ties with Israel and abandon the Abraham Accords entirely. Israel has a long history of encouraging and arming conflicts within Sudan as a response to the opposition of successive regimes in Khartoum. In this tradition, acting foreign minister Ali al-Sadiq Ali blamed Israel for encouraging the RSF during a January visit to Tehran (Press TV [Tehran], January 20). Sudanese officials have also suggested that Washington step in to halt the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) military support for the RSF before criticizing the SAF’s ties to Iran (Sudan Tribune, February 3).

Though relations between the UAE and Iran have shown signs of improvement over the last year, the issue of Sudan remains a point of contention, with the UAE being accused of providing weapons and financial support to the RSF. [2]

Iranian Drones and the Resurgence of the SAF

In March, coordinated tactics using drones, artillery, and infantry enabled the SAF to retake the old city area of Omdurman, the national radio and television headquarters, and the Wad al-Bashir Bridge, which is a vital supply link for the RSF. The success of this offensive is believed to be partly due to the arrival of modern Iranian drones (Al Jazeera, March 12; Radio Dabanga, March 17). The drones, which are also used to direct artillery strikes, operate out of the Wadi Sayidna base north of Omdurman. The RSF claims that the SAF receives air deliveries of Iranian drones twice a week out of Port Sudan (Reuters, April 10).

Iran began supplying unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to Sudan in 2008. This allowed the SAF to build a small arsenal of Ababil-3 drones, which have capabilities useful in the type of urban warfare common to the ongoing Sudanese conflict. Sudan also produces its own copy of the Ababil-3, known as the Zagil-3. Iranian Mohajer-class drones are also used by the SAF, with the latest in the series, the Mohajer-6, providing game-changing capabilities, including an arms payload of up to 150 kg (Military Africa, April 20, 2023).

First produced in 2018, the Mohajer-6 has a relatively low ceiling of 3.4 miles, which makes it vulnerable to anti-aircraft defenses. The drone has seen extensive use by Russia in its latest war against Ukraine. In mid-January, the RSF claimed to have shot down a Mohajer-6 drone in Khartoum State using a man-portable air-defense system (MANPAD) (Military Africa, January 15). The RSF released photos of another downed Mohajer-6 in Omdurman on January 28 (X/@RSFSudan, January 28; Asharq al-Awsat, January 29; Radio Dabanga, January 29). Despite these public losses, the new Iranian drones have played an important role in restoring the SAF’s military credibility.

A Red Sea Port for Iran

Citing Ahmad Hassan Muhammad, “a senior Sudanese intelligence official” and alleged advisor to General al-Burhan, the Wall Street Journal reported on March 3 that Iran had unsuccessfully pressed Sudan for permission to establish an Iranian naval port on the Red Sea in exchange for advanced weapons, drones, and a seagoing helicopter carrier (Wall Street Journal, March 3). Former Sudanese foreign minister Ali al-Sadiq Ali responded quickly and described the report as “incorrect,” saying “Iran has never asked Sudan to build an Iranian base. I recently visited Iran, and this was not discussed” (Sputnik [Moscow], March 4).

Other sources in Sudanese military intelligence suggested such an offer was likely never made, and its disclosure may have been a means for al-Burhan to express dissatisfaction with the lack of support the SAF has received from the international community (Asharq al-Awsat, March 4). An Iranian foreign ministry spokesman described the report as “baseless and politically motivated” (Radio Dabanga, March 5). SAF spokesman Brigadier General Nabil Abd Allah refuted the claim as “absolutely untrue” and denied there was any advisor to al-Burhan bearing the name Ahmad Hassan Muhammad (Sudan Tribune, March 4).

Despite the strong denials, it would be odd if Iran had not brought up the possibility of using a port on Sudan’s Red Sea coast behind closed doors, even if Iran had not asked to build a military base. An Iranian military base or port access on the western coast of the Red Sea—combined with Iran-friendly Houthis on the eastern side of the Red Sea—would make it easier for Tehran to have an armed presence along one of the world’s most important maritime routes. Iran has also recently operated three ships in and around the Red Sea. The first, operating in the Red Sea, is the IRIS Alborz, an Alvand-class British-built frigate launched in 1969 that has been modernized since. It is accompanied by the IRIS Beshehr, a Bandar Abbas-class replenishment vessel. The third is the MV Behshad, a cargo vessel believed to operate as a spy ship for Iran in the Gulf of Aden since 2021. The Behshad was alleged to have supplied information to Houthi missile groups from the Gulf of Aden but appears to have returned to Iran in April, simultaneous with a severe drop in Houthi missile attacks (Radio Dabanga, March 5; Alma Research and Education Center [Israel], April 24).

An Iranian presence would be discouraged by Egypt, which backs the SAF and has four naval ports of its own on the Red Sea. Russia, which has long sought a naval base on Sudan’s coast, would no doubt be displeased to see its Iranian ally take precedence. Relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran remain tense, and the Saudis would not be happy to see an Iranian naval base opposite its port of Jeddah, the main maritime entry point for Muslims making the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. Sudan has its own concerns. As with a Russian naval base in Port Sudan, an Iranian base could attract unwanted military attention from other powers. Sudan cannot afford to have its only modern sea-based port and main inlet for trade damaged or destroyed through military action. The United States, believed to have carried out a crippling cyber-attack on the Behshad in February, would be almost certain to reimpose sanctions on Sudan should it provide a naval port to Iran.

Conclusion

Though its need for military support against the RSF is serious, Sudan’s government is likely to take a measured approach toward improving its relations with Iran. The SAF has no more public support than the RSF and is seen by many Sudanese as too deeply involved with the Islamists who wielded power in Sudan during the three decades of Omar al-Bashir’s unpopular regime. Sudan’s Islamists, proud Sunnis who are tightly tied to the transitional government, are poor candidates to become puppets of Shi’ite Iran. Sudan’s army (commanded by Sunni Islamists) is also unlikely to commit itself militarily to the pursuit of Iranian objectives. There is, of course, the possibility of an RSF victory in the ongoing struggle, but for now, the RSF has no presence in eastern Sudan and no ties to Iran.

Sudan has no interest in seeing damaging U.S. sanctions restored after spending years trying to convince Washington it is not a state sponsor of terrorism. Once the current conflict ends, Sudan will need help, not hindrance, in its reconstruction, and will need to look further than Iran for assistance. All these factors speak against the establishment of an Iranian naval facility in Sudan or a formal alliance. If, however, Iranian assistance brings about an SAF triumph, Tehran is certain to come calling for payment in some form.

Notes:

[1] Jago Salmon: A Paramilitary Revolution: The Popular Defence Forces, Small Arms Survey, Geneva, 2007, pp.17-18.

[2] Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan, S/2024/65, January 15, 2024, pp. 14–15, 51–52.