Xinjiang Security Expo Reflects the Limits of U.S. Sanctions

Xinjiang Security Expo Reflects the Limits of U.S. Sanctions

Executive Summary:

- The annual Central Asia Digital Security Expo in Xinjiang is supported by the U.S.-sanctioned Xinjiang Public Security Bureau and brings technology firms together to network and market their products under the context of the CCP’s ongoing campaign of repression.

- Federal sanctions, due diligence, and regulatory policies have not limited U.S. exposure to human rights risks or eliminated funding for Chinese corporate R&D, which can be used to innovate the security and surveillance state.

- Nearly one third of the Expo participants analyzed have international connections, especially to the United States, in the form of overseas customers and branches, attendance at U.S. expos, or foreign regulatory approvals.

- Seemingly benign participants present alongside direct perpetrators, who have built Xinjiang Public Security Bureau infrastructure or sell torture devices used by the Bureau.

At the end of August, security and technology companies will arrive in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, for the 11th annual Central Asia Digital Security Expo (Central Asia Digital Security Expo). With support from the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau (XPSB), a U.S.-sanctioned entity, the expo will showcase the latest technologies for surveillance, policing, and social control. [1] According to its website, the expo serves to “improve the level of the northwestern region’s public security technology and prevention technology” (为全面提升西北地区公共安全技术和防范技术水平) by inviting companies to Xinjiang to collaborate and market their products (Central Asia Digital Security Expo, May 18, 2020).

An analysis of 50 companies that attended the 2024 expo highlights persistent failures of Western policies to meaningfully constrain international engagement with Xinjiang’s security industry. [2] Attendees included companies previously sanctioned for providing material aid to Russia in its full-scale invasion of Ukraine and one that manufactures torture devices used in Xinjiang detention facilities. Of the 50 participants analyzed, at least 16 have international connections, according to publicly available information. [3] International connections are defined here as selling to customers abroad, attending U.S. expos, operating offices overseas, or obtaining foreign legal certifications and regulatory approval. None of these companies has been sanctioned for complicity in genocide. A look at two firms is illustrative of the expo’s participants and their activities in Xinjiang.

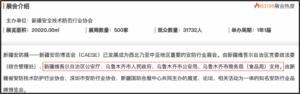

Figure 1: Registration Page for the Central Asia Digital Security Expo Acknowledges Support From the XPSB

(Source: Central Asia Digital Security Expo)

Digibird (小鸟科技) is a direct participant in the CCP’s security state through its links to the XPSB. Its monitoring systems were used in the bureau’s facilities throughout the region—including at its headquarters in Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture—as well as by the Xinjiang Prison Administration and Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (PjTime, June 3, 2016, November 9, 2016). [4] The adoption of Digibird products coincided with Chen Quanguo’s (陈全国) arrival as Xinjiang’s Party Secretary and the attendant increase in repressive policies.

According to Digibird’s official website, the company has an office in San Francisco and services customers in over 60 countries (Digibird, accessed June 16). It has completed projects for the Ministry of Defense of Malaysia and Chiang Mai University in Thailand, and its products have been approved by regulatory bodies in the United States, South Korea, and Europe (China Security Industry Network, June 19, 2017). It also has a tool listed on Apple’s App Store (Apple App Store, accessed May 12). Digibird claims to have a partnership with NASA, but while procurement filings confirm that three Digibird products were sold through an intermediary in the period 2015–2021, there appears to be no direct relationship (Solutions for Enterprise-Wide Procurement, accessed June 16).

Figure 2: Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture Public Security Bureau HQ

(Source: PjTime)

GTXD (国泰兴达) also supports the apparatus of Xinjiang’s repressive police state. The company designs and sells forensic investigation products such as DNA and drug testing equipment (GTXD, accessed June 16). It also sells an “interrogation chair” (审讯椅). More commonly known as a “tiger chair” (老虎凳), human rights experts describe it as a torture device (Human Rights Watch, May 13, 2015). Open sources do not contain evidence of any international connections, but GTXD’s presence at the expo alongside international-facing firms serves as a reminder of the expo’s purpose.

Figure 3: A ‘Tiger Chair’ Advertised by GXTD

(Source: GTXD)

Overview of Trends in International Connections

Among the 16 companies with an international presence, many export their products all over the world. One company, Everpro (长芯盛), lists 90 countries and regions (EverPro, May 2024). The majority sell to the United States, with Germany, France, Singapore, and Brazil also featuring as prominent markets. This is also true for many of the companies that have participated in expos held in the United States. For example, audiovisual technology firm Ansjer (安士佳电子) boasts customers in over 100 countries (though these are unspecified). As recently as 2020, it showcased its products at CES in Las Vegas, one of the world’s largest trade shows, suggesting direct links to the U.S. market (Devic, January 13, 2022; Ansjer, accessed June 16).

Fewer companies have established overseas branches. EverPro has a presence in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Italy, Japan, and Singapore. Another expo participant, Xi’an Jiexu Biotech (西安杰旭生物科技), does not have an overseas branch itself, but its parent company, Assure Tech (按旭生物), has at least two subsidiaries—in the United States and Singapore.

Analysis of Assure Tech’s products and corporate history shows multiple foreign regulatory approvals, including by regulatory bodies in the United States and Canada. In 2020, the company’s COVID-19 antibody tests received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The tests are sold by Thermo Fisher Scientific, an American company whose DNA sampling equipment was used by the XPSB to forcibly extract biometric data from Uyghurs (New York Times, February 21, 2019; Thermo Fisher, accessed May 20; Assure Tech, accessed June 16). The company’s current job postings for international sales positions request applicants with German, Spanish, French, and English language skills, reflecting their continued confidence in expanding across international markets (LinkedIn/Assure Tech, May 4). Several other companies at the expo have received regulatory approvals—and, in four instances, additional third-party approvals—for overseas markets. These include for the United States, Canada, South Korea, European Union, Germany, Japan, and Australia.

Regulatory certification permits the use of approved products in a specific jurisdiction, while federal and third-party approvals also tell the public that such products are safe for use. These determinations effectively legitimize and protect the reputation of the companies selling the products, support their marketing efforts, and obscure their ties to human rights abuses.

Conclusion

Past sanctions on officials and bureaus in Xinjiang have overlooked the commercial networks that underwrite Xinjiang’s security apparatus. Evidence of ties to this apparatus is publicized on companies’ official websites, in press releases, and in media reports, suggesting that businesses continue to operate unimpeded.

The expo organizers explicitly recognize the support of the XPSB. This demonstrates participating firms’ interest in the Xinjiang security market and, therefore, their complicity in the region’s human rights abuses. Ties to these companies thus pose a reputational danger to overseas firms that continue to depend on their exported technology. Operational risks are also present—PRC partner firms may find themselves subject to future sanctions designations or market restrictions.

The most urgent risk for foreign entities is the likelihood that they are currently funding human rights abuses in Xinjiang. By engaging with these firms, purchasing their products, and implementing their technologies, foreign entities are funding the research and development of companies engaged in Xinjiang’s security and surveillance state.

Notes

[1] The U.S. Department of State determined in 2021 that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had committed genocide against minority populations in Xinjiang (U.S. State Department, January 19, 2021). The following year, the European Parliament adopted a resolution that stated that CCP actions “amount to crimes against humanity and represent a serious risk of genocide” (European Parliament, June 9, 2022). Other countries’ governments have made similar declarations. In response to human rights abuses in Xinjiang, the U.S. government and others have placed sanctions on PRC officials and entities. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned former regional Party Secretary Chen Quanguo (陈全国), his deputy Zhu Hailun (朱海仑), the Director and Party Secretary of the XPSB, as well as the XPSB itself (Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, November 24, 2019; Department of Treasury, July 9, 2020).

[2] The database includes the first 57 companies included in the participant list. Seven of these companies were excluded from the analysis due to a lack of online presence (Flourish/Expo Participant Database, May 8).

[3] The true figure may well be higher (see database and sources).

[4] The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) is also known as the Bingtuan. It is a state-owned enterprise and paramilitary organization.