PRC Consolidates Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Dominance

By:

Executive Summary:

- The pharmaceutical manufacturing industry in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) appears to be consolidating around a handful of national giants such as Sino Biopharm and Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine.

- These companies occupy a large and growing presence in international supply chains and hold bottlenecks in at least three “essential medicines.”

- The PRC government has released a policy initiative targeting the pharmaceutical industry almost every year since at least 2015.

- Much of the PRC’s pharmaceutical manufacturing development is also linked to Western investment in Chinese capabilities, with leadership from companies such as AstraZeneca, Roche, and Sanofi contributing billions of dollars to research and development in the PRC and personally meeting with Xi Jinping.

In July, LaNova (礼新医药), a major international supplier of innovative biomedical technology, was acquired by the large Chinese pharmaceutical conglomerate Sino Biopharm (中国生物制药) (Sino Biopharm, July 15; BioSpace, July 16). This move comes amid substantial growth in the burgeoning pharmaceutical production and development sector within the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and has the potential to further entrench the country in both international and U.S. supply chains.

LaNova saw major development in late 2024, when Merck, an American pharmaceutical giant, paid the company nearly $600 million to further develop, produce, and commercialize its flagship LM-299 anti-cancer treatment, along with a possible $2.7 billion for technology transfer, development, regulatory approval, and additional commercialization (Merck, November 14, 2024). This agreement followed an earlier deal between LaNova and AstraZeneca for treatment of a certain type of bone marrow cancer that neared $600 million (BioSpace, May 15, 2023). These partnerships and others marked a reversal of the previous dynamics of U.S. innovation and Chinese manufacturing and point to extensive Chinese advancements in the pharmaceutical and biomedical fields. The recent acquisition of LaNova by Sino Biopharm will likely further strengthen the conglomerate and increase its overall innovation potential through LaNova’s staff and patents.

Beijing’s Rare Earths Playbook Signals Danger for API Dependence

This development is only the latest milestone in the PRC’s recent rise in the medical, biotech, and pharmaceutical fields. In particular, production in the PRC of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), the inputs that are essential to diagnose, cure, mitigate, and treat diseases, has increased rapidly in the last decade (Bioengineered, February 8, 2022). As of 2019, API manufacturers for at least three drugs identified by the U.S. Government as “essential medicines” were located solely in the PRC (FDA, October 30, 2019). Chokepoints in the pharmaceutical field can have strong ripple effects downstream and cause direct harm to patients. This was seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the Department of Health and Human Services reporting over 100 drug shortages in the United States (Johns Hopkins University, November 2020). The effect was most acute in low-cost generic drugs, whose production had been greatly outsourced abroad. During related supply chain disruptions, the U.S. government initiated emergency actions such as invoking the Defense Production Act, government stockpiling efforts, and ordering military airlifts of supplies (Congressional Research Service, December 23, 2020). Many of these shortages persist. One report found an average of 301 critical drug shortages in 2023, with 85 percent “critically or moderately” impacting patient care (American Hospital Association, May 22, 2024). While these shortages represent a dangerous and known bottleneck, there may be many more essential medicines that have not yet been discovered to be wholly reliant on Chinese manufacturing.

Information into pharmaceutical supply chains can be opaque and difficult to parse (Brookings, July 28). U.S. reliance on Chinese APIs may be anywhere between 8–47 percent, with the PRC possibly having a further stake in nearly 90 percent of global API supply chains. These estimates vary wildly due to the secondary and tertiary inputs that come from upstream processes in manufacturing, which frequently lead back to the PRC but are just as often unknown. For example, the United States reportedly receives 50 percent of its finished generic drug imports from India, while India in turn likely receives around 30 percent of its APIs and Key Starting Materials (KSMs) from the PRC (Jerin Jose Cherian et al., “Economies”, January 18, 2021; Exiger, April 16; Andrew Rechenberg, The Hill, June 22). [1] This reveals a possible additional 15 percent upstream exposure to the PRC that may have been unaccounted for in some estimates that only examine direct shipments to the United States.

When left uncovered, unknown connections, bottlenecks, and dependencies can have drastic effects on policymaking, as developments in the rare earths sector make clear. For example, the PRC controls an estimated 98 percent of raw gallium extraction as a byproduct of its aluminum production (U.S. Geological Survey, January 2023). The mineral is used in nearly all advanced semiconductors and is an essential ingredient in everything from missile defense systems to radar arrays, and even the F-35 stealth aircraft (CSIS, July 18, 2023). This gives the PRC a firm grip over these key supply chains and substantial leverage to force issues in their favor. The PRC government first moved to utilize this dependency in 2020, when its Export Control Law, which restricted access to its chokepoints, came into effect. The law included a provision for extraterritoriality to control sales beyond its immediate buyers (National People’s Congress, October 17, 2020; China Brief, March 15, 2021). Beijing made good on this threat in 2023 and 2024, when it used the new law to restrict gallium sales to U.S. buyers. In December 2024, it introduced the Dual-use Item Export Control Regulations to ban the sales outright (Medeiros, Evan and Andrew Polk, “China’s New Economic Weapons,” April 8). [2]

The U.S. government significantly underestimated the threat from these restrictions and the damage it would cause to U.S. industry and consumers (CSIS, July 17). On paper, the United States did not import much gallium from the PRC, instead trading with allies such as Japan, Germany, and Canada, and mostly importing high-purity forms of the mineral. Yet these partners’ supply chains all ran back to the PRC, and many were forced to stop trading with the United States once restrictions were implemented. Additionally, the PRC government recently tightened its grip over the mineral by introducing further export bans on the technology and techniques used for gallium extraction (Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer, July 25). These policies likely signal Beijing’s intent on maintaining this avenue of control, and an understanding of the power this leverage gives them in the international arena.

Like gallium and other minerals, the PRC’s growing presence in pharmaceutical supply chains and biomedical research represents a steadily developing chokepoint that the PRC government is keen on fostering. By 2018, estimates already showed a strong trajectory for growth. Increasing FDA approvals for pharmaceutical products coincided with Xi Jinping’s direct interest and large investments from the Made in China 2025 plan (CNBC, April 19, 2018). This attention appears to have borne fruit. According to the PRC-based Prospective Industry Research Institute, the number of Chinese API manufacturers increased 36 percent from 1,250 to 1,700 between 2018 and 2023. Likewise, API production increased from 2.3 to 3.9 metric tons, representing a 70 percent increase, while overall industry profits increased 25 percent, and are expected to grow a further 23 percent by 2030 (Prospective Industry Research Institute, April 19, 2024).

New Regulations and Courting Foreign Capital

Much of this growth appears to be linked to direct government investment, mirroring developments in other priority sectors highlighted in strategic policy documents issued by Beijing. Almost every year since 2015, the government has implemented a major policy initiative targeting the pharmaceutical industry (Sina Finance, September 5, 2024). Plans such as the 2015 National Medical and Health Service System Planning Outline (全国医疗卫生服务体系规划纲要), 2016’s Pharmaceutical Industry Development Planning Guide (医药工业发展规划指南), or the 2021 Implementation Plan for Promoting High-Quality Development of the API Industry (推动原料药产业高质量发展实施方案) all provided clear roadmaps for building the industry along with general support from the 13th and 14th Five Year Plans in 2017 and 2022 (State Council, March 6, 2015; National Health Commission, November 9, 2016; National Development and Reform Commission, November 9, 2021).

In the first half of 2025, the State Council released the “Opinions on Comprehensively Deepening Drug and Medical Device Regulatory Reform” (全面深化药品医疗器械监管改革促进医药产业高质量发展的意见), while the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA) announced “Several Measures to Support the High-Quality Development of Innovative Drugs” (支持创新药高质量发展的若干措施). Both of these documents seek to streamline regulatory requirements, provide further monetary support, and direct government resources toward supporting medical innovation, particularly big data and emerging technology (State Council, January 3; NHSA, July 1). For example, when discussing support for drug and medical device innovation (药品医疗器械研发创新的支持力度), the “Opinions” suggest establishing a regulatory body for introducing artificial intelligence and medical robots, as well as further strengthening intellectual property protections for the data gathered during R&D and clinical trials for new pharmaceuticals. Likewise, the “Several Measures” document calls for a much greater presence of newly developed drugs in the PRC’s medical system. It also demands drastically reducing the time required for drug approval down from an estimated five years to one and keeping initial pricing relatively unchanged during yearly purchasing renegotiation.

Beyond these activities, Beijing often establishes pilot and demonstration zones to cluster industries and experiment with regulations and other mechanisms (State Council, September 7, 2024). These zones are concentrated in coastal provinces and cities. Four in particular, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, and Shanghai, represent 37 percent of the PRC’s API manufacturing output, with Jiangsu being the single largest contributor (Prospective Industry Research Institute, April 19, 2024). Shanghai’s Pudong District is home to a recent large scale investment from Sino Biopharm and its partners to fund more pharmaceutical companies seeking to establish businesses in the area (Yicai Global, April 23). Further, the local government is partnering with private investment firms and loosening regulations on foreign investment to direct even more capital into developing the sector (Shanghai Government, January 17).

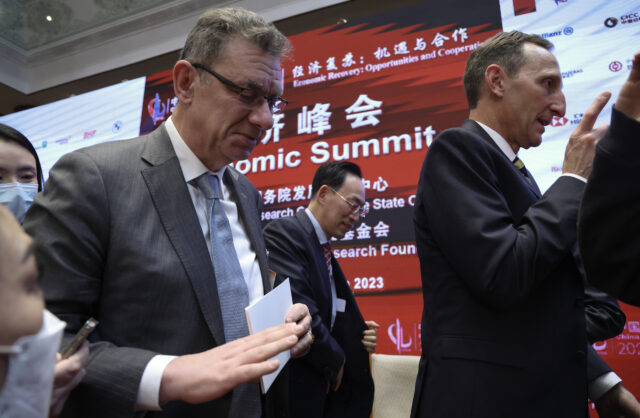

The push for foreign capital extends all the way to Xi Jinping, who in March met with leaders from leading foreign pharmaceutical firms, including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Merck, Pfizer, and others in March. The meeting reportedly lasted 90 minutes, included over 40 international CEOs and other senior leaders primarily from the pharmaceutical industry, and focused on the need to maintain global supply chains and invest in the PRC’s growth (Xinhua; Fierce Pharma, March 28). During the meeting, Xi stated directly that international investment was inseparable from the country’s economic growth (也离不开国际社会支持帮助). He also emphasized the PRC’s stability and business environment (State Council, March 28). Investments from these international firms are vital to developing Chinese pharmaceutical manufacturing, to the extent that in 2024 the PRC government refrained from punishing AstraZeneca to the full extent of the law, despite finding the company guilty of widespread medical insurance fraud (China Brief, December 6, 2024).

Early signs suggest that Beijing’s reforms of regulations and foreign investment laws may already be generating results. The months following Xi’s meeting with foreign executives saw a series of international firms investing in Chinese drug manufacturing. For example, in May the Swiss company Roche Pharmaceuticals announced a $280 million investment into Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park (张江高科技园区) to establish drug manufacturing capabilities and further integrate the region into its supply chains (Shanghai Government Foreign Affairs Office, May 9). Roche’s investment followed the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi’s announcement of a $1 billion investment in insulin production in the PRC, as well as AstraZeneca’s $2.5 billion in funding for Chinese research, development, and testing (Pharmaceutical Technology, March 24; Global Corporate Venturing, April 4). This series of investments have led Chinese media to emphasize the PRC’s “magnetic pull” (磁吸力) in drawing foreign funding to build out its pharmaceutical production capabilities (Xinhua Finance, April 1). On top of governmental support, this direct investment from international firms may well cement Chinese pharmaceutical companies’ place in international supply chains for years ahead.

Conclusion

The PRC’s ability to successfully cultivate its pharmaceutical industry will ultimately depend on the extent of international pushback. Within the U.S. government, the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security announced an API supply chain investigation in 2024 that, when released, may lead to further action to prevent another chokepoint from developing in a critical sector (U.S. Department of Commerce, July 9, 2024).

For now, while the PRC does not have complete dominance in international pharmaceutical supply chains, it is well positioned to continue to grow in that direction. The closer it comes to realizing that dominance, the more leverage Beijing will have to maintain its global interests.

Notes

[1] Cherian, Jerin Jose, Manju Rahi, Shubhra Singh, Sanapareddy Eswara Reddy, Yogendra Kumar Gupta, Vishwa Mohan Katoch, Vijay Kumar, Sakthivel Selvaraj, Payal Das, and Raman Raghunathrao Gangakhedkar. “India’s Road to Independence in Manufacturing Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: Focus on Essential Medicines.” Economies Vol. 9 No. 2 (2021): p.71. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9020071

[2] Medeiros, E. S., & Polk, A. “China’s New Economic Weapons.” The Washington Quarterly Vol. 48 No. 1 (2025): p.99–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2025.2480513