Nihilism, Denialism, and Annihilation in New Xinjiang White Paper

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 18

By:

Executive Summary:

- Xi Jinping’s personal imprimatur on the Party-state’s policies in Xinjiang are unambiguous, according to a new white paper published to coincide with a central-level delegation to the region in late September.

- The Party uses cultural and historical arguments to justify its ongoing policies of cultural erasure in the region that have been characterized by governments, parliaments, and other entities as genocidal. The white paper celebrates many of these policies.

- In defiance of Western measures aimed at curbing human rights abuses, the government actively provides support to sanctioned entities, while senior officials reject accusations of forced labor, instead blaming the United States for “unemployment” in the region.

- Beijing’s quest to normalize the situation in Xinjiang is part of a broader project that sees the region as strategically important, opening up the country to deeper trade and connectivity with Eurasia as part of its ultimate pursuit of national rejuvenation.

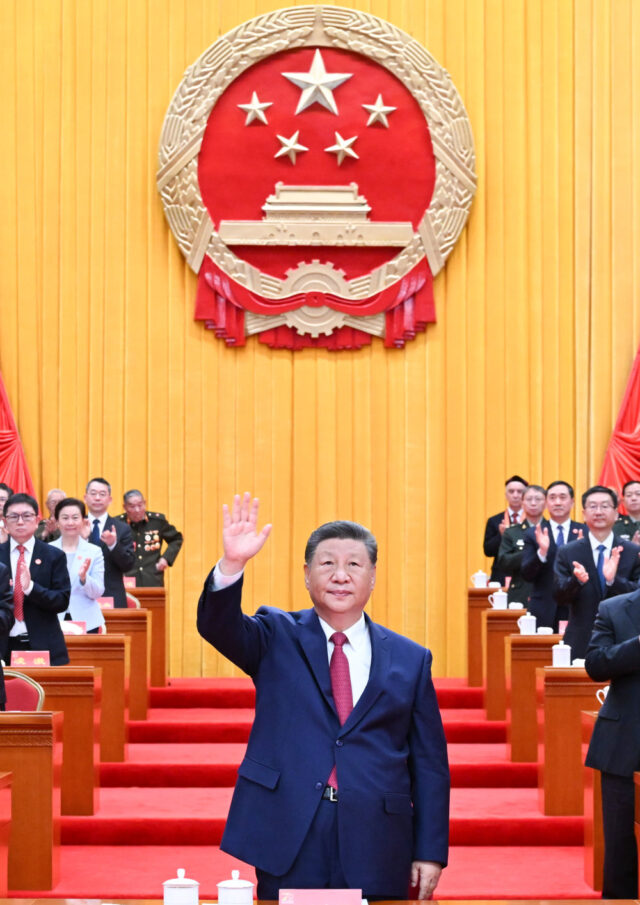

General Secretary Xi Jinping’s centrality to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) project in Xinjiang is unambiguously clear in a new white paper issued by the State Council Information Office (SCIO). Titled “CPC Guidelines for Governing Xinjiang in the New Era: Practice and Achievements” (新时代党的治疆方略的成功实践), the document has been released to coincide with a central-level delegation Xi led to the region to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the region’s founding under the PRC (CCTV, September 23). The text reads as a triumphal vindication of the Party’s work. Pushing back against international human rights concerns, it is also replete with Orwellian passages eulogizing Xinjiang’s advances in democratic processes and human rights (Xinhua, September 20).

The white paper reveals three aspects of Xi’s Xinjiang policies: nihilism, denialism, and annihilation. First, it pushes a conception of Chinese history, culture, and civilization that provides a theoretical underpinning for the Party’s domination of the region. Second, it denies evidence of genocidal actions, instead blaming the United States and other external powers for causing unrest in the region. Third, it celebrates policies of cultural erasure that seek to annihilate distinct cultural and religious practices in pursuit of forging a unitary ethnonational conception of the “Chinese nation” (中华民族).

Nihilism

Xi Jinping has long been deeply concerned about the metaphysical justification for the Party’s rule. In a departure from his preferred Marxist mode, he often emphasizes the non-material, especially when discussing issues of culture (China Brief, October 20, 2023). This is evident in claims that Xinjiang is a “sacred territory” (神圣领土) and that national unity is the central government’s “sacred mission” (神圣使命). Such pronouncements stem from fears of “cultural nihilism” (文化虚无主义). In recent years, the Party has feared external influences eroding the cultural bedrock of what it views as Chinese civilization. If not countered, these corrosive forces could lead to the collapse of not just the Party, but of Chinese civilization itself. In response, Xi has doubled down on ideology, asserting China’s cultural identity as an existential foundation and firmly establishing the “spiritual identity of the modern civilization of the Chinese nation” (树立中华民族现代文明的精神标识) (Study Times, September 4, 2023; China Brief, March 28).

The notion of Zhonghua Minzu (中华民族), an ethnonationalist conception of the Chinese nation, is at the heart of the white paper. The first full sentence of the text begins with these words, which are followed in the third sentence by the claim that Xinjiang “has been an inalienable part of China’s territory since ancient times” (新自古以来就是中国领土不可分割的一部分). The phrase also appears in the repeated articulation of the white paper’s “central theme” (主线), which appears five times in the text: “Forging the consciousness of the Zhonghua national community” (以铸牢中华民族共同体意识为主线). As the scholar James Leibold has argued, the use of the verb “forge” (铸牢) indicates that this work is part of a broader “soul-casting” project, in which the CCP is “melting down the heterogeneity of minority cultures and recasting them in Party-defined norms” (Scroll.in, September 20). The Party is clearly aware of these connotations, and so in its official English translation opts for a softer term, “fostering.”

A roster of hardline officials who see the nation through this particular lens have overseen Xinjiang policy in recent years. In 2020, Chen Xiaojiang (陈小江) was appointed as the director of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission, which manages ethnic minorities within the PRC with the principal aim of promoting national unity. Chen was the first Han director of the commission in six decades. But his two successors, Pan Yue (潘岳) and, as of September 12, Chen Ruifeng (陈瑞峰), are also Han. Pan, in particular, is a well-known ethnonationalist official. In 2024, he led the publication of a compulsory textbook for university students that promotes a Han-centric cultural and racial nationalism (China Brief, May 24, 2024).

The Party’s theories of culture and civilization—and its intolerant rejection of alternative approaches as nihilism—are intertwined with its view of history. Under the steerage of these officials and, ultimately, Xi Jinping, Party-sanctioned history has been made concrete in Xinjiang through the region’s physical cultural infrastructure. According to the white paper, the regional government has preserved key ruins and sites that “reflect past central authorities’ viable governance of Xinjiang” (中央政权有效治理新疆重点遗址遗迹保护展). This has been done, presumably, at the expense of preserving evidence that would support theories that conflict with this narrative. Meanwhile, 471 education bases for patriotism have been set up (SCIO, September 23). These efforts, downstream of the Party’s theoretical work, help to justify policies of cultural erasure.

Denialism

Evidence from the last decade—evidence that the Party has gone to considerable lengths to repress—details the brutality of the regime. On the basis of this evidence, the U.S. government has characterized Xi’s policies as genocide (U.S. Department of State, January 19, 2021). The same conclusion has been reached by the Uyghur Tribunal in the United Kingdom, as well as by Parliaments around the world (Uyghur Tribunal, December 2021). Even the United Nations, which Xi Jinping refers to as the “core” (核心) of the international system, refers to probable “crimes against humanity,” recently expressing concern about policies “increasing criminalisation of Uyghur and other minority cultural expression” (UN OHCHR, August 31, 2022, October 1).

The Party denies these accusations. The white paper acknowledges that Xinjiang has faced an “unprecedented crisis of national extinction and racial annihilation” (亡国灭种的空前危机), but this particular quote refers to the actions of Western imperialists in the nineteenth century—something that was ultimately prevented when the CCP “wisely decided to peacefully liberate Xinjiang” (中共中央英明决策和平解放新疆) in 1955. Elsewhere, officials argue that it is in fact the United States that is perpetrating abuse in Xinjiang. At the press conference for the white paper’s release, Chen Weijun (陈伟俊), Xinjiang’s vice-chairman, said that “unjustified U.S. sanctions are violating the employment rights of workers of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang under the guise of human rights protection. If there is any forcing, it is the U.S. that is doing it by forcing unemployment” (SCIO, September 23).

By framing the United States and other countries as bad-faith actors whose “purpose is political manipulation and economic bullying under the guise of human rights protection” (实质是打着“人权”的幌子搞政治操弄和经济霸凌), the Party justifies doubling down on its abusive policies. The standing committee of Xinjiang’s Party Committee has adopted resolutions “supporting the development of sanctioned enterprises and related industries” (支持受制裁企业及相关产业发展的有关决议). It also “actively provides services to sanctioned enterprises and supports them in legally safeguarding their legitimate rights and interests” (积极为受制裁企业提供服务,支持企业依法维护自身合法权益). In this way, Xi is doubling down in the face of international backlash.

Annihilation

The white paper celebrates policies of cultural erasure in Xinjiang. Often, they are justified using Party-sanctioned history. For example, claims that the Chinese script has been “in constant use” (从未中断) in Xinjiang since the Western Han (roughly two thousand years ago) are used to support the government’s efforts to “strengthen the teaching of the national standard language and script in schools” (学校国家通用语言文字教育教学持续加强). (In the press conference accompanying the white paper’s release, officials praised clips of children in Xinjiang proudly saying, “I am Chinese” (SCIO, September 23).)

The Sinicization of religion (宗教中国化)—what the white paper’s official translation euphemistically refers to as ensuring that religions “conform to China’s realities”—is also justified in this way. The text claims that a “long-standing tradition of a unified China” (中华文明长期的大一统传统) exists and that “throughout history, successive central governments in China have regarded the promotion of mainstream values and the excellence of traditional Chinese culture as an indispensable component of their governance in Xinjiang” (中国历代中央政权都将弘扬主流价值和中华优秀传统文化作为治理新疆不可或缺的重要内容). As a result, the Party believes it is entitled to “carry out activities to promote the national flag, the Constitution and laws, socialist core values, and the fine traditional Chinese culture in religious venues” (开展国旗、宪法和法律法规、社会主义核心价值观、中华优秀传统文化进宗教活动场所活动). In reality, this entails preventing the observation of religious rituals and practice, and framing attempts to do so as subversive and extremist.

The Buck Stops With Xi

The white paper makes clear throughout that Xi Jinping holds ultimate responsibility for policies enacted in Xinjiang. The preface notes that “the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core … has examined, planned, and deployed work in Xinjiang” (进入新时代,以习近平同志为核心的党中央 … 审视、谋划、部署新疆工作). Later on, it states that Xi “personally charts the course, sets the direction, and steers the ship” (亲自谋篇布局、把脉定向、领航掌舵). The conclusion, perhaps most emphatic, avers that the results of all policies in Xinjiang in the New Era are, “fundamentally, attributed to the leadership by General Secretary Xi Jinping as the core of both the CPC Central Committee and the entire Party” (根本在于习近平总书记作为党中央的核心、全党的核心领航掌舵). [1]

Xi’s focus on Xinjiang is part of a decision to raise Xinjiang’s importance in national policymaking. As the white paper states, Xi has “placed Xinjiang work in a prominent position within the overall work of the Party and the state” (把新疆工作放在党和国家工作全局的重要地位). This prominence can be tracked across PRC white papers. No other subject has been the focus of more white papers than Xinjiang in the last decade (see Table 1 below). At least one has been dedicated Xinjiang every year from 2014–2021, including three in 2019 (SCIO, accessed October 1). [2] It is also clear in the number of visits (four) that Xi has made as general secretary—more than any other autonomous region. [3]

Table 1: The 14 PRC White Papers on Xinjiang Published 2003–2025

| English Title | Chinese Title | Source & Date |

| Xinjiang’s History and Development | 新疆的历史与发展 | Xinhua, May 26, 2003 |

| Xinjiang’s History and Progress | 新疆的发展与进步 | Xinhua, September 21, 2009 |

| XPCC’s History and Development | 新疆生产建设兵团的历史与发展 | Xinhua, October 5, 2014 |

| Historical Witness to Ethnic Equality, Unity and Development in Xinjiang | 新疆各民族平等团结发展的历史见证 | Xinhua, September 25, 2015 |

| Freedom of Religious Belief in Xinjiang | 新疆的宗教信仰自由状况 | Xinhua, June 2, 2016 |

| Human Rights in Xinjiang Development and Progress | 新疆人权事业的发展进步 | Xinhua, June 1, 2017 |

| Cultural Protection and Development in Xinjiang | 新疆的文化保护与发展 | Xinhua, November 15, 2018 |

| The Fight Against Terrorism and Extremism and Human Rights Protection in Xinjiang | 新疆的反恐、去极端化斗争与人权保障 | Xinhua, March 18, 2019

|

| Historical Matters Concerning Xinjiang | 新疆的若干历史问题 | Xinhua, July 21, 2019

|

| Vocational Education and Training in Xinjiang | 新疆的职业技能教育培训工作 | Xinhua, August 16, 2019 |

| Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang | 新疆的劳动就业保障 | Xinhua, September 17, 2020 |

| Xinjiang Population Dynamics and Data | 新疆的人口发展 | Xinhua, September 26, 2021 |

| Respecting and Protecting the Rights of All Ethnic Groups in Xinjiang | 新疆各民族平等权利的保障 | Xinhua, July 14, 2021 |

| CPC Guidelines for Governing Xinjiang in the New Era: Practice and Achievements | 新时代党的治疆方略的成功实践 | Xinhua, September 20, 2025 |

Xinjiang’s “strategic importance” (战略地位) lies in its role in national strategy. Critical to achieving the overarching goal of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is becoming the preeminent power in the international system (China Brief, September 5). This requires advancing economic goals, including expanding international trade and connectivity. As an “an important gateway of Chinese civilization to the outside world” (中华文明向世界开放的重要门户), Xinjiang’s “One Port, Two Zones, Five Centers, and One Port Economic Belt” (一港、两区、五大中心、口岸经济带) is key, as it aims “to build a golden channel across the Eurasian continent and a gateway for opening up to the west” (打造亚欧黄金通道和向西开放桥头堡).

Conclusion

In Xi’s conceptual arc, repressive policies in Xinjiang have engineered a historic transformation from chaos to stability, and now to governance (由乱到稳、由稳向治的历史性转变). Under this vision, the Party is now promoting Xinjiang as an increasingly normal part of the PRC. Officials are bullish, for example, on its prospects as a holiday destination, praising a “boom” in cultural activity, and a “hot” tourism sector (SCIO, September 23). [4]

One takeaway from the Party’s increasing focus on Xinjiang over the last decade, especially in its external messaging, is that Xi himself and the regime more broadly feel vulnerable to international censure, knowing that their actions undermine their aspirations for moral legitimacy in the international system. Put another way, Xi protests too much: admission of ongoing policy support for sanctioned entities suggests policymakers are feeling the pain of international pressure.

Notes

[1] The argument that Xi personally bears responsibility for policies implemented in Xinjiang is one that is shared by outside observers. The Uyghur Tribunal report states: “The Tribunal is satisfied that President Xi Jinping … bear[s] primary responsibility for acts that have occurred in Xinjiang,” and that crimes committed “have occurred as a direct result of policies, language and speeches promoted by President Xi.”

[2] White papers are intended primarily for an external audience. They appear either when Beijing perceives a need to proactively shape a narrative, or when it feels compelled to respond to bad press in overseas media (China Brief, April 22, 2011). This helps explain a near-constant stream of white papers focused on explaining the country’s approach to human rights. It is also the reason for targeted white papers, such as ones on the PRC’s rare earths policy and claims to the Diaoyu Islands in 2012, or on Taiwan in the summer of 2022 (SCIO, June 20, 2012, September 25, 2012, August 10, 2022).

[3] In September, Xi brought with him nine senior officials, including politburo standing committee members Wang Huning (王沪宁) and Cai Qi (蔡奇). Both men had accompanied Xi the previous month to Tibet, which also has been elevated in importance under Xi’s tenure (China Brief, September 19).

[4] International actors, in acquiescing to or tacitly accepting Beijing’s narrative, risk complicity in ongoing human rights abuses in the region. As research by the Uyghur Human Rights Project uncovered earlier this year, some of the biggest international hotel chains operate in Xinjiang, are exposed to forced labor, and operate in areas administered by the Xinjiang Production and Constructions Corps—a sanctioned entity (UHRP, April 25).