New Emphases in the PLA’s Operational Centers of Gravity

By:

Executive Summary:

- Like many militaries around the world, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) places strong emphasis on Clausewitz’s concept of the center of gravity—the single most important and decisive operational problem to the PLA in a given phase or time window.

- A recent PLA Daily article places new emphasis on information-centric centers of gravity, time-sensitive targeting, and the requirement for higher-level approval.

- These three shifts reflect intensified preparations for operations against Taiwan, as well as suggesting an ongoing breakdown of trust between military authorities and frontline officers.

Carl von Clausewitz’s concept of the center of gravity remains a key analytic tool for military and operational planning that is used by armed forces worldwide. The 19th century theorist of war derived the term (Schwerpunkt, or “main point” in the original German) from its use in the physical sciences. He used it metaphorically to refer to a focal point in an enemy’s forces when its acts with a substantial degree of unity (Echevarria, 2003). [1] In military discourse within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), analysts define a “center of gravity” (作战重心) as the single most important and decisive “operational problem” (作战问题) in a conflict’s given phase or time window. Analyzing operational problems can uncover the nature and patterns of a military confrontation. This analysis focuses on real adversaries, the PLA’s own capabilities, and potential battlefields, while studying key issues such as guidance, methods, and deployment. The aim is to ensure victory in future wars and keep pace with the evolution of warfare (PLA Daily, July 7, 2022; November 24, 2022; July 8).

On October 2, Xu Shiyong (许世勇), likely a professor at the PLA Army Command College, published an article on the concept of operational centers of gravity in the PLA Daily (PLA Daily, October 2). According to Xu’s operational definition, operational or tactical planners who apply the concept well can seize the initiative on the battlefield and ultimately achieve their operational objectives (PLA Daily, April 23, 2024; October 2). Xu had previously written a piece on the concept that appeared in April 2024 (PLA Daily, April 23, 2024). [2] A comparison of the two articles suggests an evolution in the understanding of this concept within the PLA. The more recent piece focuses more on information-centric gravity, time-sensitive targeting, and approval from higher authorities. This shift in emphasis carries implications for potential operations against Taiwan as well as for recent controversies surrounding the PLA’s personnel management.

Three Aspects of ‘Center of Gravity’

Since the formation of the current Central Military Commission after the 20th Party Congress in 2022, the PLA Daily’s “Military Forum” (军事论坛) has published four articles focusing on the concept of “operational centers of gravity” (作战重心). In addition to Xu Shiyong’s two pieces that emphasize the operational application of the concept, two other articles describe its theoretical foundations (PLA Daily, May 30, 2023; August 15, 2024).

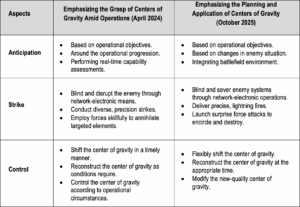

Xu Shiyong’s two articles emphasize different aspects of the concept, but both follow a similar framework that divides analysis into three areas: anticipation (预判), strike (打击), and control (调控). Each contains several subcomponents that largely overlap, though specific elements vary due to the difference in focus of the two articles (see Table 1 below). The different emphases of the two articles means that there has not necessarily been a shift in the PLA’s overall discourse on the center of gravity concept. However, the October 2025 article introduces several ideas not found in the previous three pieces. These differences deserve closer attention.

First, Xu’s second article prioritizes centers of gravity for employing “new quality combat forces” (新质战斗力). New quality combat forces refer to information-system–based, system-level combat capabilities (China Brief, March 15, 2024). A Chinese military researcher, writing in the People’s Daily, used artificial intelligence as an example, noting that machine learning and big data analytics can enable real-time situational awareness and anticipatory assessment of the battlefield, thereby improving decision-making precision, strengthening command and control, and increasing the likelihood of success in combat (People’s Daily, August 1). The article also prioritizes adjustments to a conflict’s center of gravity to secure an advantage in the effectiveness of new quality combat forces against the enemy. The piece marks the first time a discussion has linked the two concepts. It indicates that analysts must treat the information dimension as the primary consideration when assessing centers of gravity and make information-oriented adjustments the top priority.

Second, the article emphasizes striking the enemy’s “time-sensitive targets” (时敏目标)—battlefield objectives whose value depends on timing and typically consist of highly mobile, high-value enemy platforms that pose a serious threat to one’s forces and demand immediate response. According to PLA writers, destroying time-sensitive targets is decisive for reversing a deteriorating situation, seizing the initiative, and securing victory. Striking these targets requires strengthening strike capabilities that are fast, precise, and efficient and built on networked information systems, enabling near-instant neutralization through rapid, well-executed actions (PLA Daily, April 21, 2022; June 6, 2023). Writings on centers of gravity have not previously discussed this topic.

Third, the article argues that any change to the assessed center of gravity must be reported immediately to higher authorities and must receive their approval. This requirement signals that senior PLA leaders intend to strengthen real-time control over subordinate operational units because changes to the center of gravity can alter existing operational plans. New quality combat forces are supposed to make this reporting-and-approval requirement feasible. On this point too, Xu’s article is the first to discuss this aspect of chain of command protocols in the center of gravity literature.

Discussion Reflects Taiwan Focus, Distrust Within the PLA

The latest discussion of Clausewitz’s concept partly reflects the PLA’s intensified preparation for potential operations against Taiwan, which remains the PLA’s primary—and most likely—adversary in any future conflict. The reference to gaining an advantage over the enemy in new quality combat forces also could point to Taiwan. Compared with the United States, Japan, or South Korea, Taiwan’s information and communication capabilities represent a domain where the PLA likely feels more confident that it can gain superiority. The PLA also appears to be strengthening its training for time-sensitive strikes against Taiwan. As Taiwan expands its asymmetric weapons, such as coastal anti-ship missiles, the PLA counters by using long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for reconnaissance and strikes along Taiwan’s coast. Eight UAV circumnavigation flights took place during this year’s Joint Combat Readiness Patrols—up from three in 2024, all of which occurred in August. This could reflect the PLA’s growing focus on detecting and engaging time-sensitive targets.

A second implication is that tighter control over frontline units’ adjustments to operational plans partly reflects senior PLA leaders’—and possibly Xi Jinping’s—current distrust of the military. The PLA has long emphasized Party control, where top-down authority is considered essential and typically highlighted early in official writings. Yet of the four PLA Daily articles on centers of gravity, the first three made no mention of closely following higher-level orders or securing timely approval. This implies that assessing changes to the center of gravity in a conflict and adjusting based on real-time battlefield conditions was previously left to frontline commanders. An apparent reversal in the latest article to now requiring approval for any adjustment suggests Xi Jinping’s dissatisfaction with recent personnel management has eroded trust in frontline officers, prompting tighter central oversight in a domain once defined by initiative and flexibility.

Notes

[1] Echevarria II, Antulio J. “Clausewitz’s Center of Gravity: It’s Not What We Thought.” Naval War College Review, Winter 2003, Vol. LVI, No. 1.

[2] Xu Shiyong’s current position and title remain unclear, but he published research under the affiliation of the PLA Army Command College in both 2016 and 2019. See: Xu Shiyong and Ke Lisha (2016), “The Impact of Offensive–Defensive Transitions on Informatized Operations and Countermeasures (攻防转换对信息化作战的影响及对策),” National Defense Technology (国防科技); Xu Shiyong, Xu Lisheng, and Li Zongkun (2019), “Strategic Considerations for Accelerating the Development of the Army’s Power Projection Capability (加快陆军投送能力建设的战略思考),” National Defense Technology (国防科技).