Brief: Gazan “Gray-Zone Militants” Challenge U.S. Immigration Vetting

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 23 Issue: 8

By:

Executive Summary:

- A Gazan man accused of participating in the October 7 attacks entered the United States on a visa after concealing his ties to the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP). His arrest exposes gaps in immigration vetting for militants from smaller or non-Islamist factions.

- The case underscores a growing counterterrorism challenge posed by “gray-zone militants”—combatants with combat experience and ideology but unclear organizational ties, making them difficult to identify through current screening systems.

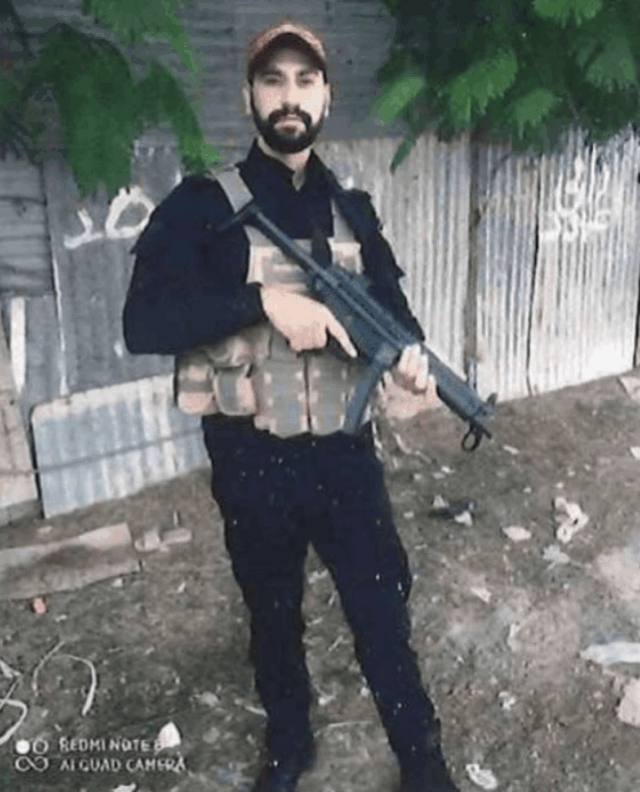

The recent detention of Mahmoud Amin Ya’qub al-Muhtadi (Arabic: محمود أمين يعقوب المهتدي) in Lafayette, Louisiana represents an uncomfortable development in U.S. counterterrorism policy. The 33-year-old Gaza-born al-Muhtadi was living in Lafayette on a temporary visa when Israeli intelligence alerted U.S. officials that al-Muhtadi’s phone had pinged a cell tower outside the Israeli community of Kfar Aza the morning of October 7, 2023 (Hebrew: כפר עזה) (ynet global, October 17). Kfar Aza, a small kibbutz (Hebrew: קיבוץ, “agricultural commune”) two miles east of the Gaza Strip, was one of the hardest-hit communities during the October 7 massacres; of the commune’s 950 inhabitants, 64 were killed that morning and another 19 taken hostage (ynet, March 5). Al-Muhtadi’s presence near Kfar Aza that morning suggests he was a militant who took part in the atrocities. The al-Muhtadi case, from his involvement in militancy to his arrival in the United States, highlights likely systemic weaknesses in vetting men from conflict zones, allowing a low-level actor from a small group to effectively slip through.

Numerous small paramilitary organizations and armed individuals joined Hamas in its October 7 attack. Al-Muhtadi was affiliated with the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (Arabic: الجبهة الديمقراطية لتحرير فلسطين, DFLP), a leftist organization related to the better-known PFLP (Arabic: الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, “Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine”), and fought as part of the DFLP’s military wing, the National Resistance Brigades (Arabic: كتائب المقاومة القومية). The DFLP was one of at least five other groups that accompanied Hamas in its invasion, many appearing to act with little top-down coordination. Among those accompanying Hamas were the Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades (Arabic: كتائب أبو علي مصطفى) of the PFLP, the Nasser Salah al-Din Brigades (Arabic: كتائب الناصر صلاح الدين), also called the Popular Resistance Brigades, which comprise a collection of different armed groups, and completely unaffiliated militants (BBC, November 27, 2023; UN Human Rights Office, June 10, 2024;

Al-Muhtadi’s group was not given advanced notice of the Hamas-led assault. The U.S. prosecution found evidence that he heard of the attack, gathered friends in his unit while telling one to “bring the rifles,” and went on to invade amidst the pandemonium (Erem News, October 17).

After leaving Gaza for Egypt sometime later, al-Muhtadi applied for a U.S. visa on June 26, 2024. On his application, he lied and claimed he had never been affiliated with a militant group. His application was approved, and he arrived in the United States on September 12, 2024, in Dallas, Texas. He then briefly lived with his children for a stint in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and then settled in Lafayette, where he worked at a restaurant (Sky News Arabia, October 18).

Western leaders have long feared deliberate infiltration by terrorist groups that send operatives to commit attacks in the countries to which they immigrate. This paradigm is built around combating deliberate infiltration by hostile groups, which has been a threat from international Salafi-jihadist organizations like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) over the past two decades. Meanwhile, groups like Hamas and even the less-renowned DFLP are blacklisted, and prospective asylum seekers with known Hamas affiliation are barred from entry. However, the existing vetting system appears ill-equipped to sideline militants from a long list of diffuse groups with complicated and only semi-documented affiliations. While the DFLP or similar organizations may be blacklisted, they do not necessarily have the organizational characteristics that make them intelligence targets, allowing immigration officials to effectively enforce the blacklisting. It appears possible that in a counterterrorism environment far more geared towards surveying high-profile Islamist groups, individuals affiliated with a small leftist militia may slip through the vetting far more easily.

Limited parallels exist among Iraqis and Syrians who immigrated in the 2000s and 2010s. These countries suffered from insurgencies by Salafi-jihadist groups, which spawned an environment of dozens of competing groups, largely operated by people who would not have attracted the attention of security services. A surprising example is this phenomenon was Salwan Momika (Arabic: سلوان موميكا) case. [1] Momika was an Iraqi anti-Islam firebrand who lied about his role in a Christian militia affiliated with Iran’s Popular Mobilization Forces (Arabic: الحشد الشعبي, PMF) when he sought asylum in Sweden (YouTube/Orient – أورينت نيوز). [2] While Momika’s activism was dangerous for himself and caused some public unrest, it was ultimately nonviolent. In other cases, former militants from the aforementioned countries went on to obtain criminal charges or demonstrate links to terrorism (ABC News, November 18, 2015; BBC News, August 26, 2024).

There is little independent information that intelligence or immigration services can use to verify risks in Gaza. In such an environment, the existing vetting procedures appear reliant on personal disclosure, making them easy to exploit. Even with Hamas’s dominance, the web of militant groups within Gaza numbers over a dozen, in addition to armed men who participate in hostilities as part of amateur militias (UNISPAL). Such individuals are unlikely to appear in databases gathered by intelligence services unless their exploits are truly unique and notable, but they retain all the key markers of militants: arms training, radicalization, connection to organizations, and sometimes combat experience. As much of the Western world juggles its humanitarian and security priorities around the Israel–Hamas War as well as other conflicts, opportunistic “gray-zone militants” like al-Muhtadi, who likely number in the thousands, pose an increasingly difficult screening dilemma.

Al-Muhtadi’s fate could set a precedent for future immigrants and asylum seekers with strong ties to militancy. It is uncertain whether al-Muhtadi was an active threat after landing in the United States, but participants in “opportunistic terrorism” need to be understood as belonging to an important gray area between “members of organized ideological groups” and civilians—especially when operating alongside the former.

Militants subverting U.S. and Western security checks should no longer be expected to do so with central direction. In an era and environment where a rag-tag leftist militia engages in joint operations with a world-renowned terrorist organization, policymakers need to understand militants as belonging within environmental milieus rather than organizational hierarchies.

[1] Momika was murdered by another asylum seeker, believed to be Bashar Zakkour from Syria, in January 2025 (SyriacPress, October 16).

[2] The Assyrian militia which Momika fought for, Kataib Rouh Allah Issa ibn Miriam (Arabic: كتائب روح الله عيسى بن مريم, “The Spirit of God, Jesus son of Mary Brigades), primarily combatted the Islamic State (IS) in his native northern Iraq, but Iran’s militias in the region were also accused of rights violations and vigilante violence against local Sunni Arabs.