New Law Reshapes Chinese Counterterrorism Policy and Operations

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 2

By:

On December 27, the National People’s Congress approved China’s new Counterterrorism Law, establishing a legal basis for counterterrorism operations and the authorities delegated to the security services for that mission (Xinhua, December 27, 2015). Earlier drafts of the law sparked international controversy after Beijing claimed the need for access to the communication and information system encryption keys used by Chinese and foreign companies operating in China. The Chinese state’s role in intellectual property theft stoked fears that Beijing was using security concerns as an excuse to exploit foreign companies. Although this provision was softened, the approved text of the Counterterrorism Law still contains a number of expansive powers, such as restrictions on press coverage of terrorist incidents. The law’s most important elements, however, address organizational changes to how the Chinese intelligence and security services conduct counterterrorism operations. The law creates a new counterterrorism policy system, which mirrors similar systems established for other security missions to improve coordination and information sharing.

Highlights of the Counterterrorism Law

The new Counterterrorism Law outlines a broad set of authorities and practices for the Ministry of State Security (MSS), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), and other parts of the political-legal apparatus.

Cooperation: Information technology and telecommunications firms are required to cooperate as requested by the appropriate authorities. This cooperation includes the possibility of providing encryption keys and data otherwise kept private within a company’s records.

Expanded Police Authority: The police can restrain the activities of terrorist suspects, including preventing them from leaving a locality, meeting with others, and taking public transport.

Use of Force: The police are allowed to use weapons against armed terrorists in the middle of an attack without prior authorization. This strange provision seems to suggest either more police officers will be armed or that confusion about what police could do in the middle of an attack had stalled the responses to attacks, like the attacks at the Kunming train station in March 2014.

Overseas Operations: The People’s Liberation Army and People’s Armed Police are authorized to execute counterterrorism operations overseas with the approval of the Central Military Commission. The Ministry of Public Security is similarly authorized with the approval of the host country and the State Council (Xinhua, December 27, 2015).

As with the Counterespionage Law passed in late 2014, the new Counterterrorism Law contains provisions that provide a legal foundation for activities that are probably already occurring (China Brief, March 6, 2015). State media also pointed out that some of the practices formalized in the new law were drawn from studies of U.S. and European security legislation. Although this obvious propaganda point is intended to undermine Western criticism of some of the law’s features, many of the authorities are not unlike how Western security services operate (Xinhua, December 27, 2015; Legal Network, December 29, 2015). The primary difference is the latter receive judicial and legal oversight for their operations and often do not possess the authority to proceed without that oversight.

The explicit discussion of Chinese armed forces and the security services operating abroad highlights Beijing’s growing willingness to use force outside China and engage in joint operations to protect Chinese overseas interests, even if such operations are not necessarily related to terrorism. An incident on October 5, 2011, in which 13 Chinese riverboat sailors were killed by drug smugglers, galvanized the government to take action (China Brief, November 11, 2011). After a flurry of negotiations, the MPS began coordinated river patrols on the Mekong River and deployed officers to Laos to provide operational support in the hunt for the drug lord, Naw Kham, responsible for the murders (Xinhua, September 19, 2012). The MPS has conducted joint operations in Angola to capture a Chinese criminal gang, and Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign led to MPS officers being deployed overseas to track fugitives and liaise with local authorities, as well as use Interpol channels to put pressure on those fugitives (Xinhua, August 25, 2012; SCMP, April 23, 2015; Xinhua, October 29, 2015). The PLA’s different service elements also appear to be seeking roles, as demonstrated by PLA Navy marines’ participation in a recent training exercise in Xinjiang (Xinhua, January 8). The need to protect Chinese citizens from kidnappings or worse (as Chinese deaths in the Boston Marathon bombings, the Islamic State execution, and the bombing in Bangkok amply demonstrate) and the inability of the Chinese government to do so probably generated momentum for the international aspects of the Counterterrorism Law (Bangkok Post, August 19, 2015; China Brief, February 3, 2012; China Brief, May 11, 2012).

Establishing a New Counterterrorism Structure

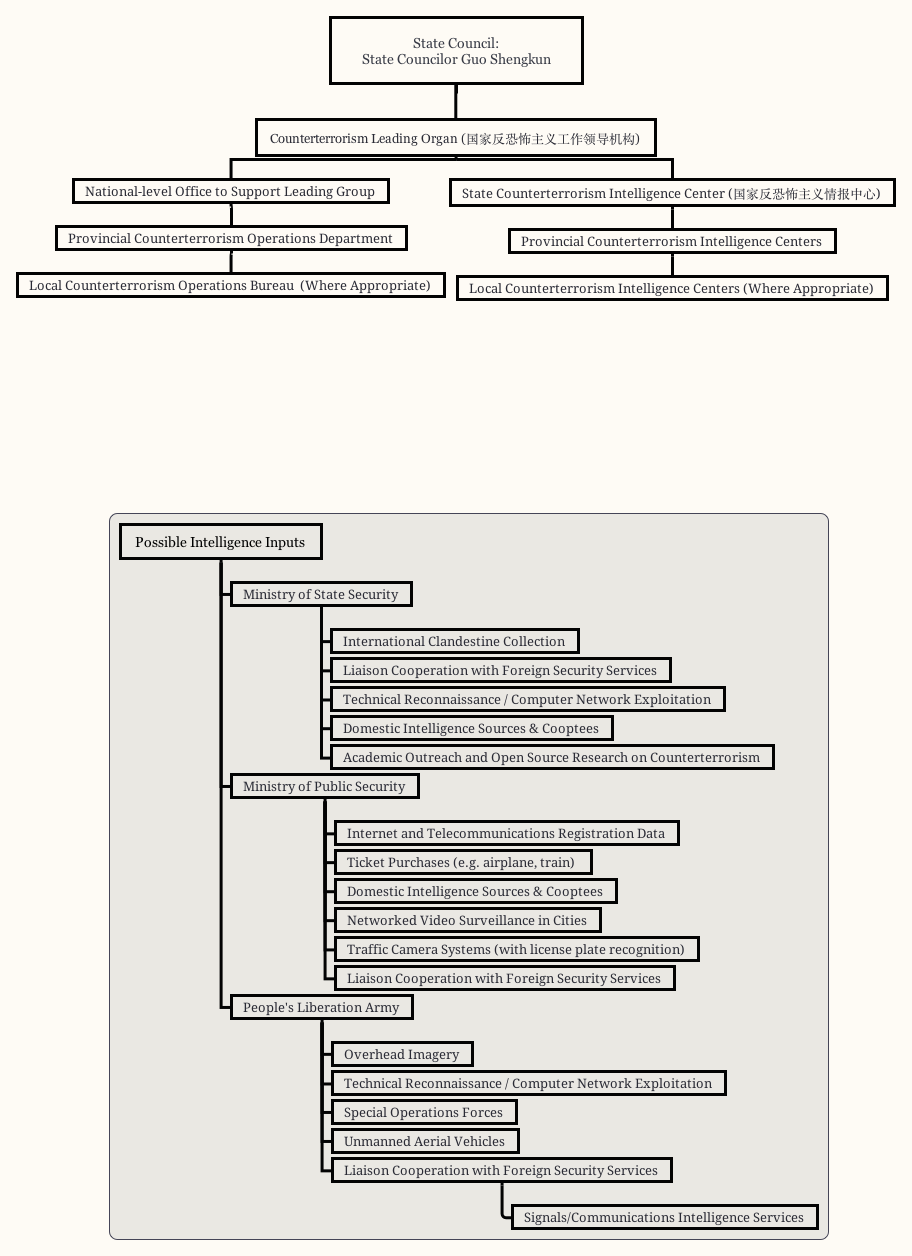

The most important provisions relate to a new policy and operations system focused on creating and implementing counterterrorism policy. The system will bring together counterterrorism elements of the MSS, MPS, and possibly the People’s Armed Police under a quasi-autonomous structure, distinct from other policymaking bodies like the Political-Legal Commission. The law contains two provisions that outline the structure of the policy system:

National institution for counterterrorism work (国家反恐怖主义工作领导机构): This leading institution at the national level will be present at every level of government at least down to the municipality. The organizations in this structure will be responsible for conducting counterterrorism operations;

State Counterterrorism Intelligence Center (国家反恐怖主义情报中心): The State Counterterrorism Intelligence Center (SCIC) would serve as an interdepartmental and inter-regional clearinghouse for “counterterrorism intelligence information work” (反恐怖主义情报信息工作) and coordinating related resources. The MPS and MSS, as well as their provincial departments and sub-provincial bureaus, therefore, would submit counterterrorism information to the SCIC. The work of the SCIC also will be buttressed by sub-national counterterrorism intelligence centers; however, the law is ambiguous about what level of government is required to set up a local center. The SCIC also will provide analytic reports and warning of terrorist activities to local security forces (Xinhua, December 27, 2015).

The law mentions each of the major political-legal institutions contributing to the new counterterrorism institutions—namely, the MSS, MPS, People’s Procuratorate, and the court system. The “relevant departments” (有关部门) could include the principal military intelligence departments within the PLA General Staff Department (or possibly the newly-established Strategic Support Force), the People’s Armed Police, and the United Front Work Department (UFWD). The relevance of the first two are obvious, but their role depends on whether the Central Military Commission authorizes their participation. The latter has responsibility for manufacturing consent among the ethnic minority groups for Beijing’s rule, and some evidence suggests the United Front system has become more involved in managing unrest in Xinjiang (China Brief, July 26, 2013). The UFWD potentially adds capabilities, including intelligence, indoctrination, and the authority to integrate outsiders, albeit in a controlled form, into the party’s political processes.

According to the law’s text, the counterterrorism intelligence system will draw upon the full capabilities of the Chinese intelligence and security apparatus. The law authorizes MPS and MSS elements to recruit sources as well as develop a broad network of contacts (“rely on the masses” and “establish a grassroots work force”) to provide tip-offs. Technical reconnaissance means, such as computer network operations, can also be employed, provided the information collected is used solely for counterterrorism operations. The law’s text is explicit on this point, probably to assuage concerns that Western companies providing their encryptions keys would be vulnerable to economic espionage (Xinhua, December 27, 2015). Additionally, the MPS is singled out for its capability to collect information on and track an individual through their identification documents and biometrics, as well as real name registration for many telecommunications and Internet services. The law authorizes the MPS to gather this data, and employ it to restrict the movements of terrorist suspects. These capabilities have been under development for some time, and the wording of the law (and the specific omission of the MSS) suggests that, without the counterterrorism law, the MSS could not draw upon these resources for state security work (China Brief, June 3, 2011). Integrating these collection capabilities under the SCIC might make the counterterrorism policy system the closest to an all-source intelligence system in China, second only to the military intelligence system.

The organizational details described in the Counterterrorism Law offer only a glimpse of what probably will be built up in the coming months, but this is not Beijing’s first effort at integrating policy and operations against a particular challenge. The closest parallel to the new counterterrorism system is the structure of the 610 Office under the Leading Small Group for the Defense and Management of Evil Cult Issues (中央防范和处理邪教问题领导小组), established to target the Falun Gong quasi-spiritual movement. Beneath the leading small group is an executive office, the 610 Office itself, which staffs the group and formulates policy. Beneath the central 610 Office, every province and down to the county or municipal level has a local 610 Office. The personnel at each level are drawn from their local MPS and MSS bureaus, and they work in the 610 Office independent of their home element. By seconding police and intelligence officers away from their home ministry, the 610 Office sharply reduces bureaucratic friction and competition. Because the MSS adopted the police rank system in the early 1990s, performance evaluations can be standardized and being assigned to the 610 Office does not obviously disrupt one’s career (Xinhua, September 16, 1992; December 23, 1992). The effectiveness of Beijing’s campaign against Falun Gong over the last 17 years suggests the 610 Office structure streamlines domestic security intelligence and operations.

Comparing the available information on the counterterrorism system to the 610 Office structure raises a few questions about the new set of organizations and how they will function. First, this system will operate under the State Council, unlike the 610 Office, which operates under the Party’s umbrella. This could signal that the UFWD or related institutions would not be included in counterterrorism. Unless a counterterrorism leading small group is established inside the Party or the State Security Committee (中央国家安全委员会) to serve as the primary authority, the new system almost certainly will be focused narrowly on security operations rather than a comprehensive counterterrorism effort. An integrated approach would be signaled by making united front work as a constituent part of the system or placing senior counterterrorism officials in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress separate from their home ministries. Otherwise, placing a Party organization like the UFWD under or integrating with a State–Council-led effort seems unlikely, if not unthinkable.

Second, the status of the counterterrorism personnel assigned to the new counterterrorism system probably will affect how well the system functions. In the 610 Office structure, police and intelligence officers are seconded over, removing them from their home agencies. For the operational elements of the counterterrorism system, mimicking the 610 Office may be the most beneficial option. The personnel work separately in an integrated office, but can later return to their home ministry. The SCIC and any sub-national elements, however, might be better served by a task force structure, more akin to the Olympic security intelligence organizations. The Chinese intelligence officers and information workers assigned would have direct connectivity back to their home offices with the ability to search for useful information and feed it into the SCIC rather than wait for the ministry to provide intelligence reporting as it determines relevance. The Olympics, however, were an exceptional political event, and Beijing may not be prepared to push such integration in a system where rivalries have been the historical norm. [1]

Conclusion

The Counterterrorism Law, in large part because of the organizational changes, marks a significant change in Beijing’s intelligence and security operations against what it considers to be terrorist targets. Although counterterrorism probably will not be on par with similarly integrated systems (Taiwan, Falun Gong, and preserving stability) led by Politburo Standing Committee members, the new authorities and institutional structure likely will be sufficient to integrate policy and operations both at home and abroad. Though the implementation remains to be seen, there is little reason to doubt NPC Chairman Zhang Dejiang’s assertions that the new law, by establishing the basic principles of counterterrorism operations, “will improve [China’s] counterterrorism capability and level” (Xinhua, December 27, 2015).

The new organizational structure for counterterrorism should smooth out some of the tensions between the MPS and MSS over which ministry has jurisdiction in terrorism cases. In China, the definitions of public security and state security complicate the handling of terrorism when the individuals involved are Chinese citizens. Ostensibly, the MPS should have primacy, but, if there is an international dimension to why these people pose a threat, then the MSS should have primacy. The difference in political clout, however, is substantial. MPS officials frequently outrank their MSS counterparts at every level of the Political-Legal Committee structure, and the former has started to encroach on the MSS’s national security prerogative (China Brief, April 12, 2013).

In addition to streamlining operations, the counterterrorism system should improve the flow of information across the relevant ministries. The creation of a national-level intelligence center above the operational counterterrorism offices establishes a clear structure outside of the MPS and MSS for who should be handling what tasks. Instead of feeding a competing ministry, the agencies will be supporting a national policy system in which clearer directions and established overarching objectives ensure a basic level of cooperative effort as can be seen in operations against Taiwan (China Brief, December 5, 2014).

Peter Mattis is a Fellow in the Jamestown Foundation’s China Program and edited China Brief from 2011 to 2013.

Note

1. David Ian Chambers, “Edging in from the Cold: The Past and Present State of Chinese Intelligence Historiography,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 56, No. 3 (September 2012), pp. 31–46.