The Growing Alliance between Uzbek Extremists and the Pakistani Taliban

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 11 Issue: 5

By:

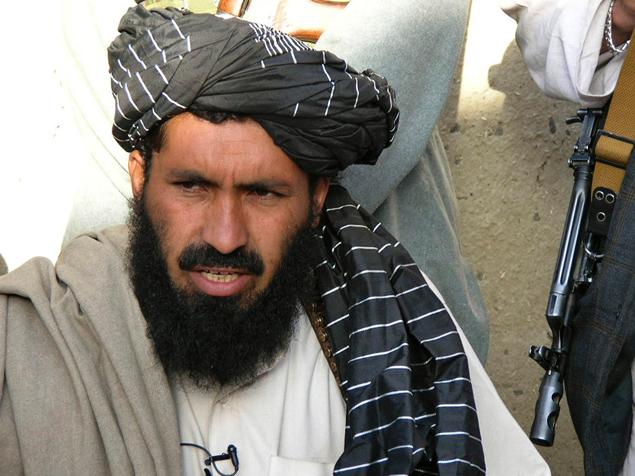

The U.S. drone strike that killed Maulvi Nazir in South Waziristan on January 2 eliminated a key local leader who resisted the presence of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) in South Waziristan. From a U.S. perspective, Nazir was a target because he provided safe havens and training camps in the South Waziristan capital of Wana from which militants could launch cross-border raids against U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan.

Nazir, however, was also an enemy of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). The TTP, or Pakistani Taliban, had opposed Nazir since the summer of 2009, when Nazir agreed to a non-aggression pact with the Pakistani government before the Pakistani army launched an offensive against the TTP in South Waziristan. Islamabad thus considered Nazir a “good Taliban,” even as he ordered his fighters to attack U.S. forces in Afghanistan (Dawn [Karachi], January 4).

Like the TTP, the IMU also opposed Nazir, and only five weeks before the drone strike that killed Nazir on January 2, a teenage suicide bomber sent by the IMU (likely with TTP backing) failed in an attempt to kill Nazir in Wana (The News [Islamabad], November 29, 2012). The IMU rivalry with Nazir began in 2007, when Nazir ordered an estimated 3,000 of his fighters to expel the IMU from Wana (see Terrorism Monitor, January 14, 2008). In the fighting, between 50 and 200 IMU militants were killed, while hundreds of other Uzbeks fled to other areas of South Waziristan and North Waziristan and possibly even to Afghanistan to join the Afghan Taliban in Helmand Province (Newsline [Karachi], June 10, 2007).

The Uzbeks in the IMU first arrived in South Waziristan en masse in 2002 to escape the U.S. rout of the IMU from its bases in northern Afghanistan. However, Nazir disliked the Uzbeks because they were reluctant to carry out attacks against U.S. forces in Afghanistan, focusing instead on carrying out joint attacks with the TTP against the Pakistani government. In addition, the Uzbeks who settled in South Waziristan increasingly interfered with local tribal and religious affairs, which angered Nazir.

With Nazir eliminated, it falls upon his successor, Bahawal Khan, to maintain the truce with the Pakistani army. However, if Khan is unable to do so, or if Nazir’s fighters seek revenge against the Pakistan government for allegedly aiding the U.S. drone program, then the truce between Nazir’s fighters and Pakistan may not hold. This would allow the IMU to reassert itself in Wana and carry out more attacks in Peshawar and the tribal areas, where the IMU has been increasingly active in recent months.

IMU militants participated in a TTP attack on the Peshawar air force base on December 16, 2012 that killed five people. This attack conformed to the TTP’s recent strategy of avoiding large-scale attacks in cities that kill a large number of civilians in favor of targeting military installations (The Nation [Islamabad], December 17, 2012). According to Pakistani security officers, IMU militants are known for their “ferocity, alacrity and training” and willingness to participate in high-risk operations (Dawn, December 18, 2012). Such operations include the attack on Mehran Naval base in Karachi on May 22, 2011, which was launched in retaliation for Osama bin Laden’s death, and the August 2012 attack on the Kamra Air base of the Pakistan Air Force in the Punjab region (The News [Islamabad], December 18, 2012; Dawn [Karachi], December 18, 2012). In Afghanistan, major IMU attacks include an attack on Bagram airbase in 2010 and an October 2011 attack on a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) base in Panjshir (Der Spiegel, January 18, 2011; AP, October 16, 2011).

The IMU also played a key role in the Bannu prison break in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province that freed Adnan Rashid and nearly 400 other prisoners, including an estimated 200 Taliban fighters, on April 15, 2012. Rashid was in the Pakistani air force when in 2003 he was found guilty and placed on death row for plotting to assassinate then President Musharraf—a charge which Rashid confessed to after the escape.

A TTP Uzbek language video released in May 2012 shows the IMU preparing for the prison break and says that the plan was devised after Rashid wrote a message seeking help to Abu Ibrahim al-Almani (a.k.a Yassin Chouka), a German of Moroccan descent who was designated a “global terrorist” by the United States for serving as a “fighter, recruiter, facilitator and propagandist” of the IMU. [1] According to the video, the operation to free Rashid was ordered by Hakimullah Mahsud, the overall leader of the TTP, and Waliur Rahman Mahsud, the leader of the TTP in South Waziristan (Online News [Islamabad], May 16, 2012).

In August 2012, a German-subtitled video released by the IMU´s JundAllah media wing featured Rashid speaking in Arabic and English about his time in prison. He described the night of the prison break, saying: “I saw my release in a dream about 20 days ago before the operation… I saw in the dream that some Uzbek mujahideen will come and will take me out of the prison.” Months later, on January 31, 2013, both the IMU’s JundAllah studio and the TTP’s Umar studio issued a “joint video message in support of the prisoners,” featuring Rashid, Abu Ibrahim al-Almani and Abdul Hakim, a Russian commander in the IMU. They declared that the IMU and the TTP have created a special unit called Ansar al-Asir (Supporters of Prisoners), whose aim is to free other imprisoned militants in Pakistan and target Pakistani intelligence agents, army personnel and prison staff (The News [Islamabad], February 7).

The integration of the IMU and the TTP has been displayed openly since September 2010, when the IMU’s JundAllah media agency posted a video online showing the successor of IMU founder Tahir Yuldash, the late Osman Adil, meeting with TTP leader Hakimullah Mahsud and his second-in-command, Waliur Rahman Mahsud (Furqon.com, January 15). These joint IMU-TTP videos are now commonplace. In December 2012 the IMU mufti, Abu Zar al-Burmi, even released a statement through the TTP’s Umar Studios in which he accused the West of hypocrisy for condemning the TTP’s attempted assassination of 13-year old Malala Yousufzal, while “having killed hundreds of innocent Pakistanis” themselves (As-ansar.com, December 27, 2012).

The IMU and TTP alliance in South Waziristan is likely to be strengthened by Maulvi Nazir’s death. For the TTP, this means that the IMU can continue to assist the TTP in attacking targets in Pakistan. For the soon to be departed U.S. forces in Afghanistan, this also means that the attacks from South Waziristan are likely to continue in an effort to hasten the withdrawal and portray the Taliban, the IMU and other allied militant groups as victors. For the IMU, Nazir’s elimination will help the movement secure the safe havens it needs in Pakistan’s tribal areas to pursue its long-term goal of establishing an Islamic State in Uzbekistan and the entire Central Asian region.

Note

1. U.S. Department of State, “Terrorist Designations of Yassin Chouka, Monir Chouka and Mevlut Kar,” January 26, 2012, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/01/182550.htm.

Jacob Zenn is an Analyst of Eurasian and African Affairs for The Jamestown Foundation. He presented testimony on the Islamist Militant Threats to Central Asia to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in February 2013. He is also a non-resident research fellow of the Center for Shanghai Cooperation Studies (COSCOS) in Shanghai, China.