Will Tajikistan’s Karategin Valley Again Become a Militant Stronghold?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 166

By:

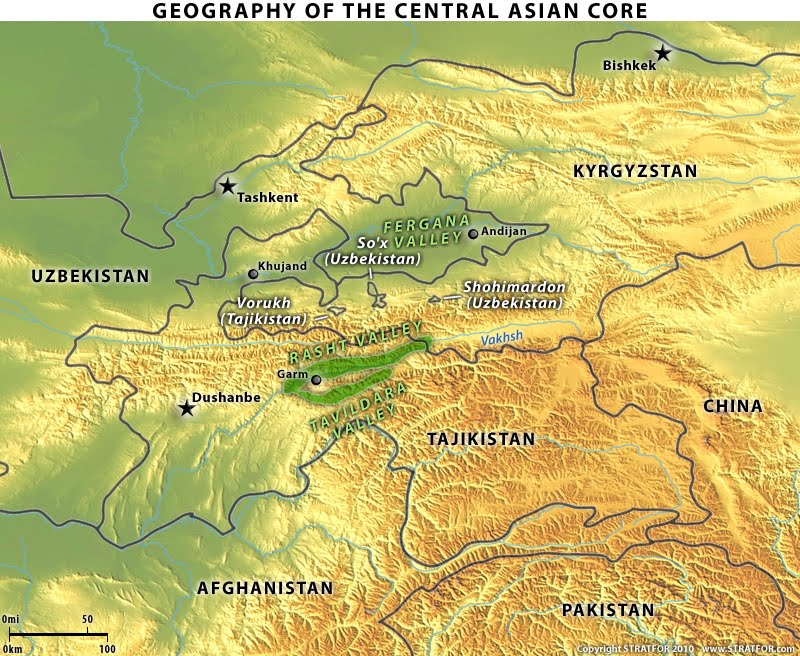

The Karategin (literally “black mountains”) Valley—also called Rasht Valley, located in the West-Central part of the country—is a very special region of Tajikistan. During the 1992–1997 Tajikistan Civil War, the Karategin was a stronghold for the Islamic opposition and became the site of numerous battles with militant groups. Notably, four members of the United Nations Mission of Observers in Tajikistan were murdered here in 1998 (UN Press Release, November 12, 1998). As of 2011, the government has succeeded in pacifying the region, but the end of the West’s mission in Afghanistan by 2014 threatens to reignite hostilities in the Karategin in the near future.

The special role of the Karategin Valley as a base of operations for militant groups originally stems from its ethnic cleavages. The region has traditionally been the homeland of the so-called Garm people (Garm is the main town in the Karategin Valley)—a minority ethnic group of Tajiks. Tribalism is a very serious problem for Tajikistan; the Tajiks have failed to unite into a single nation, and the political struggle here has been practically indivisible from the inter-regional and inter-ethnic one. Indeed, during the Civil War, a coalition of Garm and Pamir Tajiks fought against Kuliab and Hudjand Tajiks.

The author visited the Karategin Valley during the battle between government-backed Kuliab troops and the opposition in 1995 and witnessed Kuliab soldiers behaving like foreign occupiers. Banditry was a common occurrence in Garm-populated villages occupied by Kuliab troops. Kuliab soldiers privately told Jamestown that the Garm people were “very bad Tajiks” and it would be better to kill all local residents in the valley.

In 1996, opposition Islamic fighters (mujahideen) managed to seize this part of Tajikistan. The author visited Karategin that year and found the new regime was not much better than the previous. Even the appearance of the mujahideen was threatening to the local population: the mujahideen wore their hair long and had long beards. The Islamic fighters tried to govern the population in line with Sharia law, with all decisions of the mujahidin taken at meetings in the mosque. Local residents told Jamestown that the mujahideen had sometimes forced them to pray at the mosque five times a day under threat of punishment. When out in public, women were forced to wear scarves covering the whole face except the eyes. The sale of alcohol was strictly forbidden in the Karategin Valley, and cigarettes were banned as well. In addition, the mujahideen banned music at weddings, except for religious music played on traditional instruments.

Yet, several punishments devised by the mujahideen did not conform to traditional Sharia standards. Criminals were beaten in the mosques not with a stick (as Sharia law dictates), but with the shell of a hand-held grenade launcher. Also, large metal tanks were placed in some villages. The accused was put in the tank which was then beaten with a stick. Local people told the author that often the victim’s eardrums burst after this form of punishment.

February 1999 terrorist attacks in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, frightened the Uzbekistani authorities into indiscriminately arresting religious dissenters. Consequently, emigration from Uzbekistan to Tajikistan became a mass movement, with whole families fleeing and resettling in the Karategin Valley. Military camps also sprang up alongside civilian Uzbek settlements in the Karategin. Official circles in Dushanbe even discussed seriously allocating parts of the Karategin Valley for Uzbeks to live in, where a “free Islamic Uzbekistan in exile” would be established (Forum 18, November 12, 2003).

Fighters of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) thus lived in the Karategin Valley until 2000. Fighters from Uzbekistan fought side by side with Tajikistan’s opposition as early as 1992. Moreover, in 1996, one of the leaders of the IMU, Juma Namangani (given name, Jumma Kasinov), became first deputy to the most influential field commander of Karategin, Mirzo Zieev, who was killed in 2009.

In 1999, the author visited an IMU training camp near Hait in the Karategin Valley. A typical day for IMU militants was broken into two parts—in the morning, they were trained in subversive operations techniques, while the second half of the day was devoted to indoctrination. For instance, the trainees were shown footage featuring the struggles of Islamic militants with the “unfaithful” the world over. Kyrgyzstani military officers interviewed by Jamestown reported that arms, ammunition and food were actually airlifted to these Uzbek fighters by planes of Tajikistan’s Ministry for Emergency Situations, headed by Mirzo Zieev.

Minister Zieev, in an interview with Jamestown, denied that arms and ammunition had been airlifted to the Karategin-based IMU by Tajikistan’s Emergency Situations Ministry. According to Zieev, the Ministry did not have planes. Zieev also said he had actually convinced Jumma Namangani to leave Tajikistan, which apparently offended the IMU leader (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, December 14, 2000).

In the summer of 1999, Tajikistan-based IMU militants launched an armed attack from the Karategin in an attempt to break into Uzbekistan through the territory of Kyrgyzstan. After long and heavy fighting with the armed forces of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, the militants withdrew back to Tajikistan. Next year, however, the militants regrouped and invaded both Kyrgyzstan and the Surkhandarya administrative region of Uzbekistan. Detachments of some local Tajik field commanders from the Karategin Valley (for example, Abdullo Rahimov—a.k.a. Mullo Abdullo—from Komsomolabad and Eribek Ibraghimov—a.k.a. the “Sheikh”—from Tajikabad) also took part in these armed Uzbek Islamic raids. In the fall of 2000, most IMU fighters moved from Tajikistan to Afghanistan. Some Karategin field commanders, for example Mullo Abdullo, also relocated to Afghanistan together with the IMU (see TM, December 18, 2003).

Yet, hostilities returned to the heart of Tajikistan within a decade. In May 2009, Mullo Abdullo returned with his fighters to the Karategin Valley from Afghanistan, and government troops responded by carrying out military operations against them. According to Dushanbe, in July 2009, Mirzo Zieev supported the rebellion and was killed during the battle (ferghana.ru, July 13, 2009). Furthermore, in 2010, more than two dozen prisoners, including two of Mirzo Zieev’s sons, escaped from a detention center in the capital of Tajikistan after a bloody shootout. All were originally arrested during fighting in the Karategin Valley in July 2009 (Reuters, August 23, 2010; Kommersant, August 24, 2010). These escaped prisoners returned to the Karategin, sparking new military operations in the region by the government. On September 19, 2010, a defense ministry convoy seeking to apprehend the excaped prisoners came under grenade attack in Kamarob Gorge in the Karategin Valley. At least 28 soldiers were killed. The authorities blamed Abdullo for the ambush and additional government forces were sent to the area to hunt down the attackers (BBC, September 20, 2010). After a prolonged period of heavy fighting, the militants were destroyed, but the resistance in the Karategin Valley was only extinguished on April 15, 2011, when Abdullo was killed (Lenta.ru, April 17, 2011).

After Mullo Abdullo’s death, Dushanbe completed clearing the Karategin Valley of its independent warlords, placing the region firmly under the government’s control. The recent military operation in Pamir (the other region where the influence of former opposition field commanders was also strong; see EDM, July 27, August 1) shows that Tajikistan’s government believes that “the Karategin problem” has been resolved. Furthermore, as the author concludes from his travels to the area, local residents of the Karategin Valley are so tired of living through war that they are ready to accept administrative leadership originating from any region of Tajikistan.

But the situation is likely to change after NATO and US forces withdraw from Afghanistan after 2014. At that point, Tajik militants who fought in Afghanistan may return home to continue the struggle. These mujahideen will probably attempt to settle in the Karategin Valley and the Pamir region, which are both traditionally opposed to the pro-government Kuliab clan. Uzbek militants who fought in Afghanistan could also again use Karategin valley as a staging point for an attack on Uzbekistan, thus spreading the conflict beyond Tajikistan’s borders.