Moscow Can Use West-European Partners in South Stream Project

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 156

By:

South Stream, the Russian-led project company, considers moving its legal address and changing its registration from Switzerland to the Netherlands. The reasons behind this internal debate are not being disclosed as yet. Reportedly, Italian ENI favors this proposal. Earlier this year, ENI registered a company, South Stream BV, in Amsterdam as a subsidiary of South Stream Transport AG, according to Moscow insider reports (Interfax Oil and Gas weekly report, August 13).

The proposed relocation, if executed, would mark the South Stream project company’s third registration within a short period of time, all in the process of affixing a West European face on a Kremlin project. This project company is in charge South Stream’s section on the seabed of the Black Sea, from Russia to Bulgaria (not the overland sections in Europe). Initially a joint venture of Gazprom with ENI on a parity basis, this offshore project changed its structure in September 2011 at Gazprom’s initiative. Under the new shareholder agreement, Gazprom retains its 50 percent of shares intact; ENI has been reduced to 20 percent of shares; while German BASF/Wintershall and Gaz de France have acquired 15 percent each. South Stream had to undergo a new registration by December 2011, technically necessitating a new name as South Stream Transport AG. The existing shareholder agreements must be signed again with each registration, which would again be the case in the event of relocating from Zug (Switzerland) to the Netherlands. Such changes are common among small companies in risky ventures, but are highly unusual for large and established companies in flagship projects.

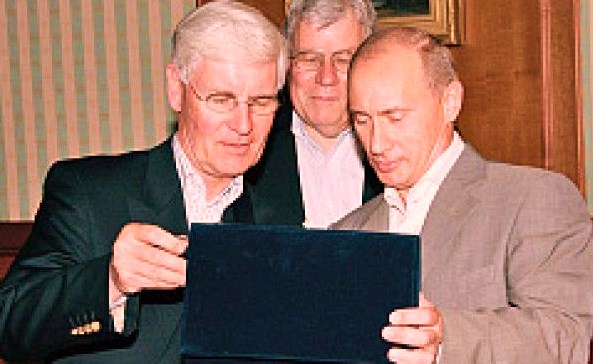

While coopting BASF/Wintershall and Gaz de France into its project, Gazprom recruited the outgoing CEO of Nederlandse Gasunie, Marcel Kramer, as South Stream Transport AG’s CEO. It has also picked Henning Voscherau, the Social-Democrat former long-serving mayor of Hamburg, as chairman of the board of South Stream Transport. He has no background in the energy sector but is a highly-connected politician and a popular, somewhat folksy figure in northern Germany. Earlier this year, Voscherau was considered as a nominee for President of Germany, following the incumbent Christian Wulff’s forced resignation under conflict-of-interest charges. Voscherau did not become a candidate; instead, Gazprom invited him to chair South Stream’s board – a symmetrical counterpart to Gerhard Schroeder, board chairman to Gazprom’s Nord Stream project in the Baltic Sea.

Henning Voscherau’s brother, Eggert Voscherau, a long-serving BASF executive, chairs since 2009 the BASF supervisory board. Thus, both brothers look set for key roles in the South Stream project. Eggert Voscherau also happens to have been appointed in 2006 a member of the board of Nord Stream. According to a German observer of the energy sector, “Russians can regularly appoint friends and relatives to manage political and economic projects, not only in Russia, but more recently also in Germany” (Wirtschafts Woche, March 19).

Moscow expects from such allies to lobby for Western political acceptance and financing of Gazprom’s projects. South Stream is a Gazprom-executed Kremlin initiative, planned to advance Russia’s interests, and driven by President Vladimir Putin personally. Moreover, it clashes head-on with the European Union’s energy policy (a common European policy, undermined however by unilateral German policies). Moscow’s business allies are lobbying in Brussels for TEN-E (Trans-European Networks-Energy) status to be conferred by the EU to South Stream. To legalize this project in Europe and secure Western financing, South Stream must be presented as international in its composition and European in its objectives. “This is an all-European, multilateral project,” Putin insists (www.kremlin.ru, July 24).

The three European companies in South Stream are tight-lipped about their goals in joining this project. In the case of ENI, those goals seem subject to changes depending on market and macroeconomic shifts. Initially, ENI’s role was to provide its advanced technology for laying South Stream’s offshore section on the seabed. In the last two years, ENI has evidenced second thoughts about its participation, seeking changes to or even an honorable exit from South Stream’s overland section to Italy. At the moment, ENI seeks to postpone the final investment decision, despite Moscow’s attempts to precipitate that decision (see EDM, July 26, 27). Gaz de France has yet to explain its interest in building the South Stream pipeline on the seabed of the Black Sea (unlike ENI, the French company does not seem to consider becoming involved in South Stream’s overland pipeline sections).

The objectives of BASF/Wintershall in South Stream seem at least partly transparent. As a general policy, this company has long been at the forefront of cross-investments and asset-swaps with Gazprom. These are practices that Moscow seeks to generalize among West-European champion companies. In South Stream’s case, BASF/Wintershall seems to pursue two goals in exchange for supporting South Stream. One goal is access to Siberian gas extraction projects in joint ventures with Gazprom. Another goal is marketing Russian gas from the South Stream pipeline in countries of Southeastern and Central Europe, as a middleman for Gazprom there.

In March 2011, while negotiating its accession to the South Stream project, BASF/Wintershall agreed to take the 15 percent stake in return for new long-term supply contracts benefiting its subsidiary, Wintershall Natural Gas Trading (WIIE Wintershall Erdgashandelshaus). This trading subsidiary acts as a middleman for Gazprom’s supplies to several EU member countries heavily dependent on Russian gas. According to the German company, “together [with Gazprom] we strengthen the supply security of Southeastern European member countries of the EU.” In October 2011, BASF/Wintershall and Gazprom signed a framework agreement on joint-venture development of the Achimov Blocs 4 and 5 (sections of the west-Siberian Urengoy field, planned to produce 8 billion cubic meters of gas annually from 2015 onward) in exchange for Gazprom acquiring 50 percent of the German company’s stakes in two North Sea gas fields (press releases, March 21, 23; December 1, 9, 2011).

Those countries, where BASF/Wintershall intends as Gazprom’s middleman to “strengthen the supply security,” include participant countries in the EU-backed Nabucco project. South Stream is calculated to compete with the Nabucco project and stop its implementation pre-emptively. It is also designed to frustrate the implementation of the EU’s Third Energy Package (“unbundling” gas supply from gas transportation). Gazprom’s gas-transportation joint ventures with German companies are at issue in that context. These motivations account at least in part for Moscow’s enlistment of West-European companies in the South Stream project.