Moscow Examines an Alternative Vision of Military Professionalism

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 184

By:

Last week the official Russian defense ministry publication Krasnaya Zvezda carried a three-part article devoted to the American officer corps and its professional experience. The article placed the American officer corps within a civil society, addressed the unique professional isolation of the officer corps, but then remarked upon the intellectual vitality of that officer corps and its impact on the contemporary development of military art and sciences. Major-General Sergei Pechurov entitled the series Chto dvizhet Amerikanskim ofitserom (What Motivates the American Officer?) (Krasnaya Zvezda, September 25, 26, 29). Pechurov is a graduate of the prestigious Military Institute of Foreign Languages (Eastern Faculty), he served abroad in the Middle East, and attended military schools in the U.K. and Canada, and holds a doctorate in military sciences as well as having written numerous articles devoted to foreign military history and affairs.

Pechurov began by making reference to Samuel Huntington’s classic study, “The Soldier and the State,” but defined objective civilian control in terms of a conservative profession of arms within a liberal society, which separates the officer corps from the rest of society even as it employs the separation of powers between the President as Commander-in-Chief and the Congress, which controls the resources and has the explicit power to declare war, to ensure civilian control: “Therefore, control over the armed forces was gradually fragmentized and in a sense “blurred” among all the institutions of power in the United States.”

His critical assessment noted that Americans expect their officers to be educated with a mastery of the profession of arms and able to prepare the force for war. The profession of arms in this manner is isolated from civil society by its own norms and its very way of thinking which stresses “universal, concrete and permanent,” values. But, Pechurov notes, the American officer is not to be a jingoist. Others –politicians, philosophers, journalists, and academics– may clamor for the use of force and romanticize war, but not the officer corps. Officers are responsible for preparing the force for war but understand the costs in blood and treasure that will result (Krasnaya Zvezda, September 25, 26, 29).

Indeed, in going to war Americans expect their conflicts to express their values, to be about achieving overarching national objectives in keeping with a just cause. The very idealism of American society drives the tendency to turn a conflict into a crusade. Pechurov draws attention to both World Wars being conflicts fought with such justifications as opposed to the limited wars of the Cold War, such as Korea and Vietnam. In those two cases, “the views of the military were little heeded, and the ‘halo of sanctity of the case’ for which some had to die on the battlefield, was not observed.” In the cast of the meta-terrorist acts of 9/11, American society found sufficient cause to declare “a total war on terrorism” justifying the invasion of Afghanistan and later Iraq.

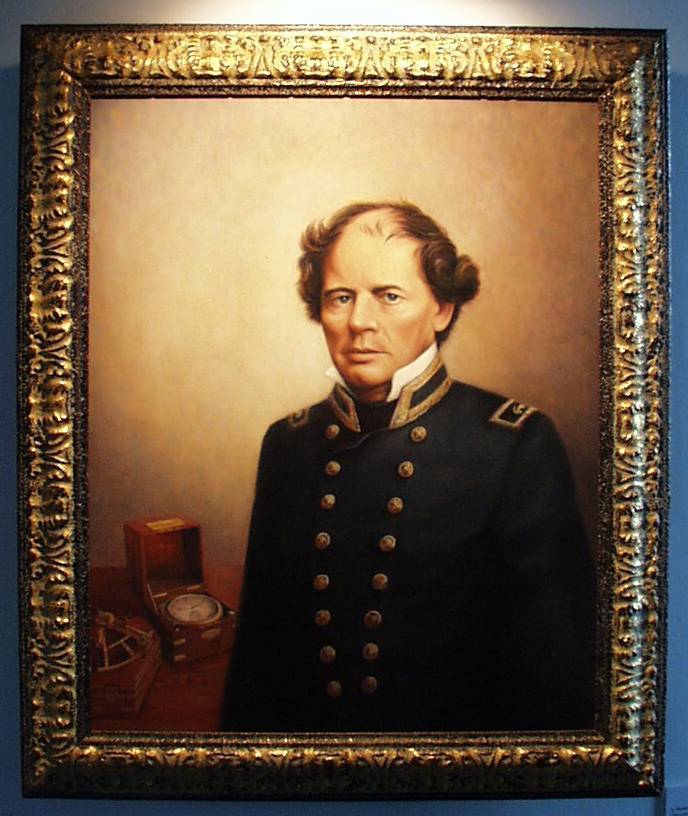

Pechurov sees in the American officer corps a serious interest in military arts and sciences, which took a distinctly different path than that of the British, French, and German military traditions, which was already evident in the mid-19th century in the work of the great maritime scholar Matthew Fontaine Maury, the father of Annapolis, and Dennis Hart Mahan, who influenced generations of officers tactics at West Point. While noting the supposed anti-intellectualism of General Norman Schwartzkopf, Pechurov points to awards this officer received while a student at Fort Benning.

Pechurov specifically mentioned the intellectual credentials of General Eric Shinseki, Admiral William Owen and Vice Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski, which he praised for their contributions to the development of the “revolutionary theory of network-centric warfare . . . now widely studied as new classics of military art.” He also noted the contribution of Colonel Douglas A. Macgregor to reshaping the force that would go to war: his book “Breaking the Phalanx” “offered ground troops to break the deadlock, restructure, and reorganize the unwieldy divisions into smaller, more flexible, rapidly deployable so-called battle groups.” The brigade revolution in the U.S. army placed a premium on adaptive leadership; a challenge now facing the Russian military. However, Macgregor retired as a colonel, reflecting the fact that the U.S. military has not found an easy place for theorists to thrive. The school house has no long-term place for the professional officer. Indeed, many senior officers speak of the need to restore a warrior ethos and see intellectuals as dangerous to the profession of arms. This tends to re-emphasize the isolation of the officer corps from civil society (Krasnaya Zvezda, September 25, 26, 29).

This series of articles is highly significant, as the Russian armed forces are currently undergoing systemic military transformation, and reveals potentially important shifts in their thinking. For the last two decades one of the most important stumbling blocks to successful military reform and transformation has been the self-referential vision of the military profession held by most Russian officers. Such conservatism is not unique to the Russian military, but it was a particular impediment when placed in juxtaposition to the radically different environment in which the Russian armed forces have had to operate.

Pechurov’s analysis might be dismissed by skeptics as little more than know your probable enemy, but for its attention to the problem of a military professional operating in a civil society, which the Russian military after two decades of failed reform has been unable to address. The very idea of senior officers finding careers outside the military is quite uncommon. Aleksandr Lebed being the most noted example of an officer who was willing to give up his uniform to engage in electoral politics.