BRIEFS

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 13 Issue: 6

By:

HOUTHIS OPEN DOOR TO GREATER IRANIAN ROLE IN YEMEN

James Brandon

Internal sectarian and political divisions have continued to deepen in Yemen in recent weeks, creating fresh instability and uncertainty. This was highlighted by President Abd Rabbo Mansur Hadi’s decision to relocate his government from the capital Sana’a to the southern port city of Aden, after fleeing Sana’a where he had been held under house arrest by the Houthi Shi’a rebel group, which now controls the capital and northern, upland parts of the country. Hadi reportedly said that Aden had become “Yemen’s capital” due to his move (al-Jazeera, March 7). This was followed by GCC governments transferring their embassies to Aden, in a show of support for Hadi, with Qatar and Saudi Arabia moving their embassies on February 25, and Kuwait, Bahrain and the UAE following two days later (al-Sharq al-Awsat, February 27; al-Arabiya, February 28; Bahrain News Agency, February 28). The United States and United Kingdom have meanwhile moved some their remaining diplomats in the country to Aden, although they have not formally relocated their embassies, which remain closed in Sana’a. The UK additionally replaced their former ambassador, Jane Marriot, who was widely seen as inexperienced and occasionally tactless, with Edmund Fitton-Brown, a veteran Arabist who has nearly 20 years of experience in the Arab world and who enjoys extensive contacts in the Gulf (UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, February 23). The effect of these moves has been to demonstrate a united GCC, U.S. and UK front against the Houthis, in support of Hadi.

In Sana’a, the Houthis have responded to these moves to isolate them with a series of gestures, apparently intended to demonstrate both their hold on northern Yemen, their self-sufficiency and their deepening links to Iran. Most notably, on March 1, the first scheduled direct Iran-Yemen airline flight since the 1980s took place, with an Iranian Mahan Air aircraft landing at Sana’a, allegedly carrying what the Iranian Red Crescent described as “12 tons of medical devices and medicines” (Saba New Agency, March 1). This followed an agreement between the Houthis and Iran to operate up to 12 direct flights per week between the two countries and to allow Iranian “cooperation” in a range of aviation-related fields, such as airport operations and runway maintenance (Saba News Agency, February 28). This agreement seems intended to allow Iran to provide the Houthis with both a door to the outside world and also a source of technical expertise. In addition, the Houthis held military drills near the Saudi border on March 12, involving infantry, jeeps and artillery. Although a Houthi spokesman said that the actions were not intended to “pose a threat to anyone,” they were presumably intended as a warning to Saudi Arabia against intervening against the movement (Press TV, March 12). It is worth noting, however, that the Houthis’ isolation is less complete than it may appear in Western and GCC capitals. China, India and Russia all maintain their diplomatic presences in Sana’a, and China—a key investor in the country—in particular enjoys deep and long-standing connections with Yemen dating to the 1950s.

On the surface, the effect of these moves is to highlight, and perhaps accelerate, the Houthis’ drift towards the Iranian camp on one hand, and the GCC’s determination to prevent a viable Shi’a-dominated government taking root in the Arabian Peninsula on the other. At the same time, however, Hadi’s move to Aden, and his overt backing by the GCC, is unlikely to be universally welcomed locally; despite an infusion of Wahhabism into Aden during the past two decades, a significant section of Adenis (who mostly subscribe to the Shafi’i school of Islam), remain staunchly secular and/or inclined to Sufism. Many consequently regard Gulf-sponsored Salafism as an unwelcome foreign import, threatening the city’s traditionally more tolerant and open culture. In addition, representatives of the southern separatist movement, al-Hirak, have criticized the relocation of government bodies to Aden, characterizing this as importing northern Yemen’s problems to the south, no doubt fearing that the president’s relocation will hinder their own aspirations (Anadolu Agency, March 6). Meanwhile, Hadi’s “Popular Committees” militia has begun a de facto purge of potentially anti-Hadi southerners in Aden, for instance forcibly removing Abd al-Hafez Muhammad al-Saqqaf, a well-known member of a distinguished southern family, as the commander of the Special Security Forces in Aden (Yemen Times, March 11). Al-Saqqaf’s removal triggered brief but intense violence in the city on March 19 (al-Jazeera, March 19). To the likely further consternation of the Aden separatists, Hadi (who is himself from southern Yemen) is also backed by al-Islah, the Yemeni wing of the Muslim Brotherhood, which has refused to talk part in talks with the Houthis without Hadi (Yemen Times, March 11). Islah, which has long opposed southern separatism, itself remains engaged in a war of words with the Houthis, whose leader recently described Islah as pursuing a “dirty, negative, unethical, non-Islamic” strategy and alleged that there is “clear and open alliance between Islah and al-Qaeda” (al-Manar, February 26).

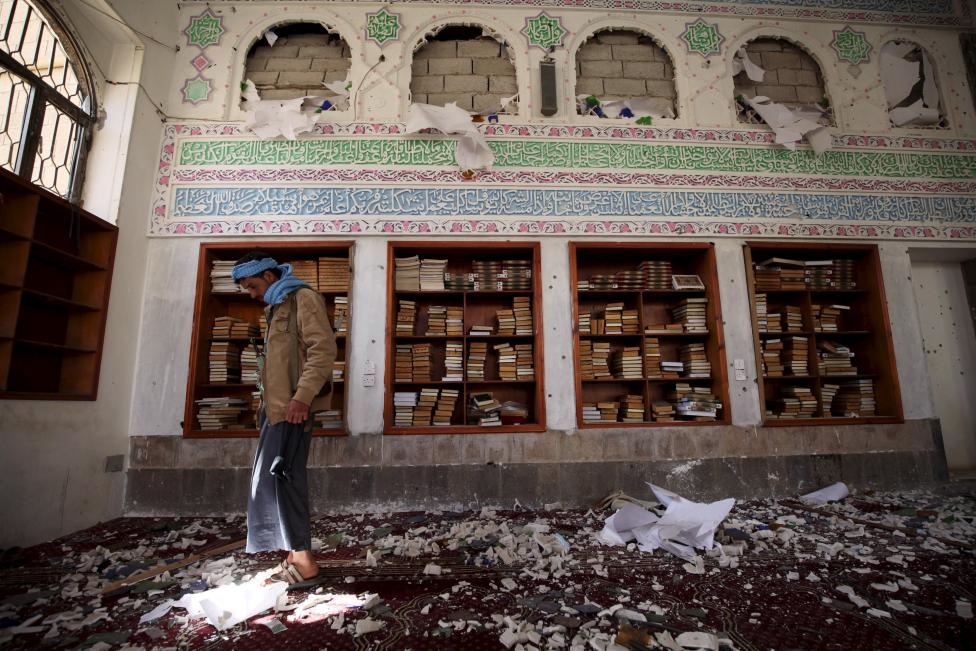

One risk posed by these developments is that the deliberate isolation of the Shi’a Houthis by the mainly Sunni GCC, with the support of Western nations, will accelerate the Houthis drift towards Iran and stoke Sunni-Shi’a political sectarianism that has largely been unknown in Yemenis, as shown the March 20 attacks on Zaydi mosques in Sana’a (Reuters, March 20). Such a development would potentially make any long term accommodation between the Houthis and GCC-backed factions harder to reach, as well as laying the groundwork for more overtly sectarian conflicts in the future. That said, the recent history of Yemen shows that apparently durable alliances are liable to collapse rapidly and that yesterday’s enemies can quickly become today’s friends; consequently a face-saving rapprochement between the Houthis and Hadi, and even between the Houthis and their arch-enemies Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Islah, cannot be ruled out. Such a deal would potentially restore a measure of calm to the country, at least in the short term.

MALI ATTACK HIGHLIGHTS CONTINUING JIHADIST THREAT

James Brandon

A lone Islamist attacker killed four people—two Malians, one French and one Belgian citizen—in a gun and grenade attack on a bar in Mali’s capital Bamako on the evening of March 7, before being killed himself by the security services. The attack was later claimed by the al-Murabitun jihadist movement via audio message. The recording said that the attack had been carried out to “avenge our Prophet” who had been “insulted and mocked” (Maliweb.net, March 9). The message also said the attack had been carried out in revenge for killing Ahmed al-Tilemsi, a founding member of the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA), who was killed in Mali in December 2014 during a battle with French special forces. Al-Tilemsi had also been an important member of al-Murabitun, which was itself formed by a 2013 merger between MUJWA and a smaller Salafi-Jihadist group run by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a veteran Algerian militant (RFI, December 11, 2014). The attack was the first fatal terrorist event in Bamako in several years, underlining the continuing jihadist presence in the country. However, the audio message also claimed a failed January assassination attempt against General Mohamed Ould Meydou, a senior ethnic Arab officer in the Malian Army, whose perpetrators were previously unknown. A suspected accomplice of the attacker was killed in a Malian special forces raid in the following week (Maliweb.net, March 16).

The attack potentially indicates that ethnic Tuareg and Arab Islamist insurgents, who are mainly confined to sparsely-inhabited northern Mali, may be seeking to bring the conflict to the capital. In addition, the nature of the attack, conducted against civilian targets associated with foreign interests, is strongly reminiscent of tactics by other Islamist militant groups worldwide, and potentially suggests that the group is shifting away from insurgency-style, mainly-rural operations toward conducting more terrorist attacks in urban areas. This shooting attack also comes soon after preliminary peace talks between the Malian government and representatives of various Arab and Tuareg armed rebel groups in Algeria. These talks ended positively in early March, with the Malian government signing the deal on March 1, and representatives of the main separatist rebel groups, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad—MNLA) and the Arab Movement for Azawad (Mouvement arabe de l’Azawad—MAA), promising to return to northern Mali to consult their grassroots supporters before signing it themselves (Algerie Presse Service, March 1). The Bamako attack, coming just days after this progress, may have been intended by al-Murabitun to signal their opposition to the proposed agreement and their determination to continue fighting. Since then, the Coordination of Azawad Movements (Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad—CMA), an umbrella group of different rebel organizations, rejected the current version of the proposed accord on March 16, although they said that it offered a basis for further negotiations (Maliweb.net, March 17).

At the same time, however, hit-and-run guerrilla attacks have continued in the north. Most notably, a UN base in the northern city of Kidal was struck by around 30 rockets, killing two local civilians and one Chadian soldier (Maliweb.net, March 8). No group has so far claimed responsibility for the attack. Meanwhile, ethnic tensions remain a key driver of the continuing violence in the region, underscoring how the conflict in northern Mali has polarized communities that had previously lived in relative harmony. For instance, in one recent bout of violence, two innocent ethnic-Arab teenagers were attacked, disemboweled and then burnt alive by locals in the aftermath of a suspected militant grenade attack on a nearby police station in the northern city of Gao (Maliweb.net, March 11; France24, March 10). The developments underscore that even if the main Malian northern rebel groups do reach an agreement with the government, northern Mali is likely to remain unstable for some time to come.