New Government Continues Mongolia’s Rebalance to China

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 18

By:

The Mongolian People’s Party (MPP) came to power in a land-slide election in June 2016 due to the dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party’s (DP) economic policies. However, in outlining its economic development and foreign relations priorities, the MPP has made it clear that it intends to continue a core element of the previous government’s approach: active engagement with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Indeed, while less referenced in MPP talking points on the country’s foreign engagement, early indications suggest the Party largely preferences alignment with the PRC over its “third neighbor” partners as its support is more direct and far less conditional (Sonin.mn, October 17). Although China’s anger at Dalai Lama’s visit to Mongolia has prompted it to cancel a number of high-level meetings, this policy predilection—a legacy of the Democratic Party-led (DP) government—will likely continue a reorientation of Mongolia’s strategic approach to foreign relations that began in 2014 (Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 23).

Initially seen as the party intent on limiting Chinese influence, the DP altered its approach to the PRC in response to the country’s economic slowdown and essential abandonment by foreign investors. One can trace this policy shift to August 2014, when the DP-led government agreed to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with China aimed at deepening policy linkages, and to November 2015, when it signed an additional agreement with Beijing for further integration (Mongolia Ministry of Foreign Affairs, April 15, 2015; Xinhua, November 11, 2015). Far from politics as usual, these two agreements marked a fundamental change in Mongolia’s approach to China prioritizing interconnectivity over concerns of dependency.

As part of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, the DP-led government agreed to establish the Mongolian-Chinese Intergovernmental Joint Commission on Economic, Trade and Technology and the Mongolian-Chinese Mine and Energy Integration Cooperation Committee. Both formal mechanisms are meant to improve coordination between the two states’ economic systems (Xinhua, August 22). Within these frameworks, Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj established an annual trade exposition in China’s Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region (IMAR), a free trade zone between the two states in Erlian and Zamiin-Uud, and an economic corridor linking China and Russia through Mongolia: all key policy priorities for Beijing (Montsame, October 26, 2015). In 2014, the two states signed the Medium-Term Development Program for Mongolian-Chinese Economic and Trade Cooperation and agreed to double their bilateral annual trade to $10 billion by 2020 and to raise the amount of their currency swap agreement; both developments predicated on far greater Chinese involvement in the Mongolian economy than in the past (Mongolian Ministry of Commerce, November 11, 2015). The DP-led government also agreed to advance coordination between Mongolia’s national development strategy, the “Steppe Road Development Plan,” and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) including the “holy trinity” of mining, construction and financial cooperation (Xinhua August 22, 2014). As a result of these policy alignments, China became much more integrated in Mongolia’s domestic economic sector than before (ASAN Forum, April 7).

In addition to economic alignment, the DP-led government also pushed for greater integration with China across the two states’ political and security sectors (Xinhua, August 19, 2014). As part of the 2014 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement, for instance, the DP-led government agreed to greater political integration with Beijing, including regular, formalized meetings between the two states” respective legislatures. In 2014, for example, Mongolia’s Speaker of Parliament Zandaakhuu Enkhbold signed a memorandum of understanding with the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress Zhang Dejiang to establish a formal mechanism for engagement and exchange between Mongolia’s Parliament and China’s National People’s Congress (Xinhua, October 27, 2014). This agreement led to unprecedented levels of cooperation between Mongolia and China’s political elite.

Mongolia and China also expanded their security engagement under the DP-led government in a variety of spheres such as military-led cooperation on humanitarian and disaster relief, counter-terrorism, border security and transnational crime. In 2014, President Elbegdorj called on Mongolia’s Department of Defense and the Mongolian Armed Forces to develop deeper ties with China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) for communication, strategic trust, and training purposes (UB Post, October 11, 2015). In 2015, the two states held their first ever joint-training activity for Special Forces and counter-terrorism called “Falcon 2015.” Training included gunnery, helicopter fast-roping, and joint hostage rescue. Mongolia’s Minister of Defense, Tserendash Tsolmon, called for more regular and higher-level military cooperation between Mongolia and China immediately after the training exercise (Xinhua, October 16, 2015).

Continuing the Tilt Toward China

Within weeks of taking power, the MPP made it clear that it would continue and expand the DP-led government’s engagement approach with China. In August 2016, for instance, Speaker of Parliament Miyegombo Enkhbold and Prime Minister Jargaltulga Erdenebat—both senior MPP members—identified cooperation with China and the need for a more relaxed foreign investment environment as essential components for Mongolia’s growth in the short- to medium-terms (Nikkei, July 1). Prime Minister Erdenebat called for greater cooperation with China across the two states’ mineral resource, infrastructure, agriculture, transportation, and financial sectors during a meeting with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in October 2016. The same month, Prime Minister Erdenebat also pledged Mongolian cooperation with China’s BRI on infrastructure development in a separate meeting with senior Communist Party of China (CCP) official Liu Yunshan in Ulaanbaatar (Xinhua, October 1). MPP leadership has expressed its inclination to allow the Bank of China (BOC) to establish an office in Mongolia; a move the DP-led government was unwilling to take due to lobbying efforts from the country’s domestic banking industry. As the BOC would offer far lower interest rates than Mongolia’s domestic banks, its presence in the country would fundamentally alter its financial system and create additional state dependency on Chinese financing (Sonin.mn, October 24).

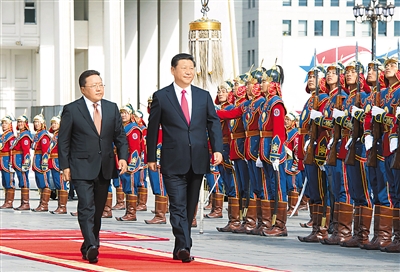

The MPP has also expressed its intent to establish greater political linkages with the PRC. In his October 2016 meeting with Liu Yunshan, for instance, Prime Minister Erdenebat called for greater political engagement and coordination between Ulaanbaatar and Beijing, stating the two states must “cement” their strategic partnership (Xinhua, October 1). The same month, Speaker of Parliament Enkhbold met with President Xi in Beijing and called for continued, high-level exchange between the MPP and the CCP. Speaker Enkhbold also pledged enhanced engagement between Mongolia’s Parliament and China’s National People’s Congress in direct response to President Xi’s call for greater bilateral collaboration on governance issues (Xinhua, October 19).

The MPP has also continued the DP-led government’s approach to security relations with Beijing. On October 17, the Chief of the General Staff of the Mongolian Armed Forces, Dulamsurengiin Davaa, called for a strengthening of Mongolian-Chinese military relations, to include higher-level cooperation and more frequent joint exercises, in a meeting with the Vice Chairman of China’s Central Military Commission Xu Qiliang (China Military Online, October 17). General Davaa noted that closer political and security cooperation with China is one of MPP-led government’s top foreign policy goals.

The Rebalance’s Driving Force

Both the DP- and MPP-led governments employ the same rationale for pursuing closer ties with the PRC: that bandwagoning with China provides Mongolia the best opportunity for economic development and growth (News.mn, October 24). By all accounts, China has emerged as Mongolia’s primary source of trade, finance, investment, and aid since the two states signed the 2014 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership; a central position within Mongolia’s domestic economy that is likely to expand as the two states further consolidate their economic linkages (Mongolian Ministry of Commerce, December 12, 2015). Mongolia’s other “third neighbor” partners, conversely, continue to have limited influence over the country’s economic development. Japan, for instance, receives only 0.45 percent of Mongolia’s exports; a base number likely to increase by only 5 percent following the two states’ FTA (UB Post, October 27). Russia—often wrongly identified as Mongolia’s “alternative” partner—is now a secondary economic actor for the state: its interests becoming increasingly limited with each passing year (Asan Forum, December 23, 2015). Even engagement with the IMF, which many analysts argue is the MPP’s way of avoiding over dependency on China, cannot compete with the allure of PRC financing to Mongolia, whether in the shape of a currency swap agreement or a $4 billion line of credit.

As such, one can best understand the MPP’s 2016–2020 Government Action Plan (GAP) as a manifesto for greater engagement with China in line with the 2014 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. More specifically, the GAP’s singular reliance on foreign investment to finance the state’s domestic-level economic goals such as debt reduction, stabilization of the macro-economy, the expansion/rejuvenation of the country’s mining sector, and economic diversification, were clearly drafted with the PRC in mind (Mongolian Parliament, August 26). No other state nor institution comes remotely close to matching the PRC’s ability to stimulate Mongolia’s economic through trade, investment, and/or aid. Neither is it certain the MPP-led government prefers alternative partnerships—including the IMF—to greater economic dependency on China (News.mn, October 13).

Importantly, Mongolia’s shift toward engagement with the PRC coincides with China’s own foreign policy reorientation away from greater power relations toward periphery diplomacy. Under the Xi Jinping administration, for instance, China has prioritized its ties with its neighboring states above its relations with great powers (with the potential exception of the United States) (Huanqiu, January 13, 2015). Within this larger paradigm shift, Mongolia has emerged as a strategic partner for China in terms of regional influence, peripheral security, and access to markets in the country’s near and far abroad (Xinhua, April 23, 2015). The Mongolian government’s decision to align more closely with the PRC since 2014 has not, therefore, occurred in a vacuum. Rather, Mongolian-Chinese linkages have deepened as both states have redefined their contemporary strategic challenges to see partnership as beneficial, if not essential. While China’s reaction to the Dalai Lama’s visit has caused a diplomatic flap, and China clearly intends to attempt to leverage the temporary cancelation of talks, such rhetoric does little to change the fundamentals of the two countries’ relationships.

Conclusion

The MPP’s decision to continue the DP-led government’s engagement strategy toward China highlights two important conditions in Mongolia’s contemporary political-economic situation. First, the Mongolian government—regardless of its precise party composition—lacks the agency to direct the country’s economy through entirely domestic means. Rather, as outlined in the GAP, Mongolia has become dependent on its external environment for growth opportunities and economic stability. This reliance creates vulnerabilities within Mongolia’s economic sector that the state lacks the capacity to mitigate absent foreign involvement. This inability raises questions about Mongolia’s domestic sovereignty or, at the very least, about the government’s ability to control the state’s domestic institutions.

Second, Mongolia has become reliant on China for its economic growth and stability to the point where the benefits of economic engagement outweigh the potential risk of overdependence. This understanding of Chinese influence is a fundamental break with Mongolia’s past strategic thinking. As recently as 2010, for instance, the Mongolian government drafted a National Security Concept that specifically called for decreased dependency on China through a network of foreign partners, or “third neighbors.” While the DP and MPP continue to pursue foreign relations that demonstrate the pretext of diplomatic diversity—most notably with Russia, Japan, and the International Monetary Fund—both parties’ clear preference for engagement China since 2014 undermines this approach. For the MPP in particular, partnership with China has become largely preferable to engagement with the state’s increasingly distant “third neighbors”; none of which have anywhere near the material capacity or political will to challenge China’s position in Mongolia (Sonin.mn, October 25).

Mongolians concerned about China’s growing influence over the state are unlikely to take much solace in the state of affairs. Rather than offer an alternative model for engagement with China, the MPP seems intent on accepting political and security linkages with the PRC as the price to pay for closer economic integration with the state. The MPP may justify these linkages with the understanding that Mongolia’s strategic options are limited and that the state’s “third neighbor” policy, while symbolically important, has lost its practical application (if, indeed, it ever had one). More likely, however, is that the MPP pursues its integration approach to China while continuing to engage with other state and institutional actors to preserve the appearance of broad engagement. While there is nothing inherently wrong in this model, particularly if Mongolia’s engagement with China leads to growth with secondary effects on the country’s human security, it is, however, important for analysts to acknowledge China’s structural power over Mongolia’s domestic and foreign policies. Failure to do so is failure to understand Mongolia’s political and economic systems as they actually are, not as Western states, in particular, would like to see them.

Dr. Jeffrey Reeves is an Associate Professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies. The views expressed are his own.