Philippines Choose Chinese Investment Over Territorial Defense

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 6

By:

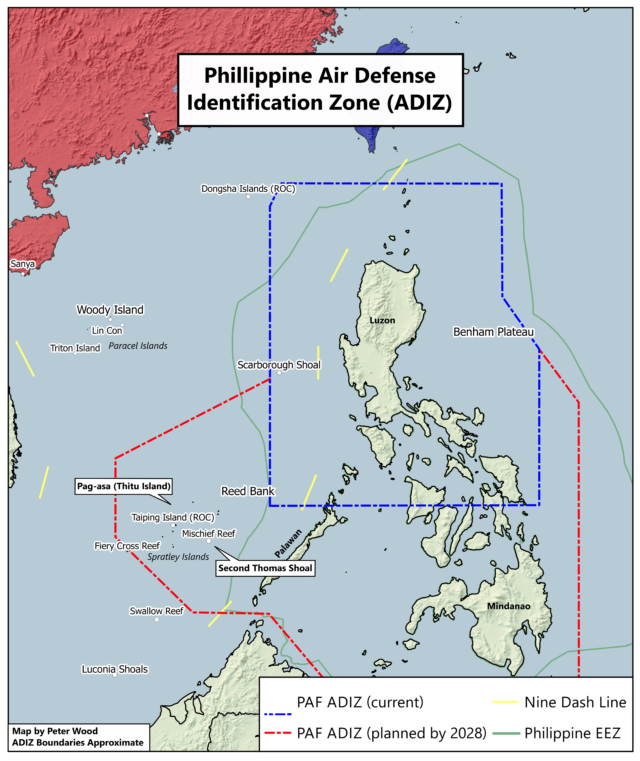

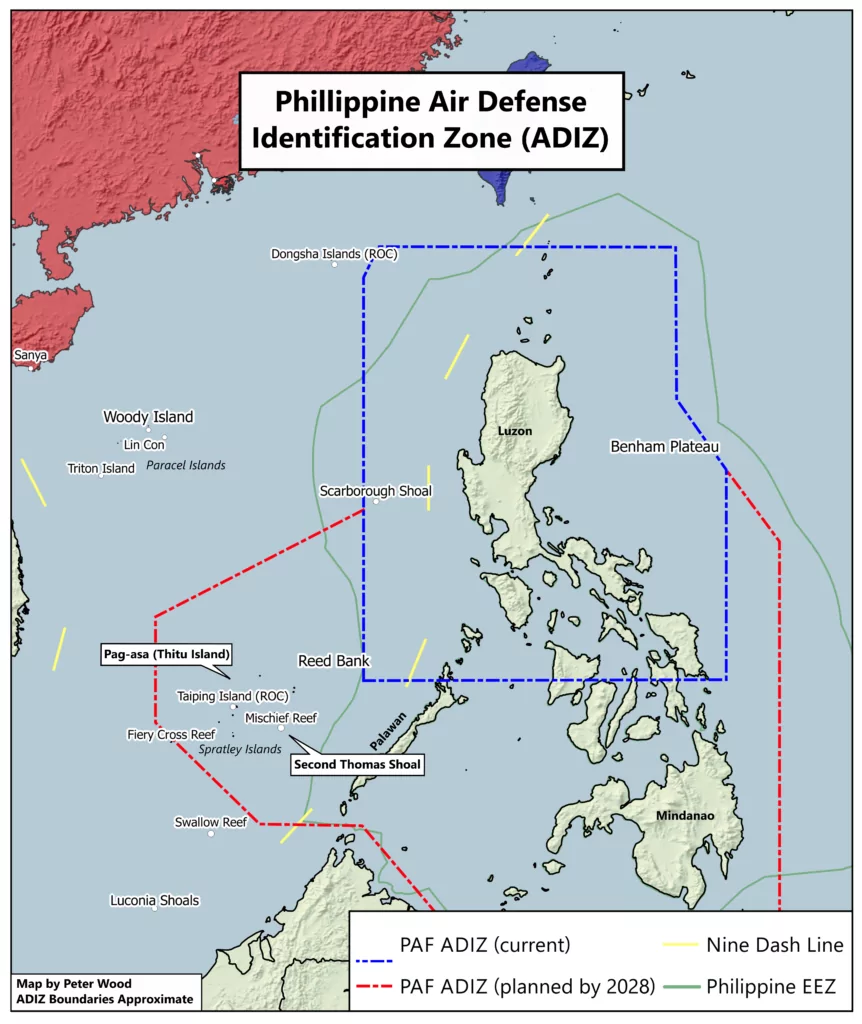

In early April, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte made waves by promising to improve Philippine defenses on islands in the South China Sea. “We have to fortify. I must build bunkers there or houses and make provisions for habitation.” Renovation and expansion of facilities on Paga-Asa (Thitu Island) “has my full support” (Philippine Star, April 7; Manila Bulletin, April 17). Additional comments claimed that the Philippine armed forces would seize unoccupied islands, and that Duterte himself would plant a flag in Pag-asa. Duterte adopted this stance after questions were raised about his close relations with China and increasing number of apparent violations of Philippine sovereignty. Philippine defense officials announced in March, for example, that Chinese vessels were detected near Benham Plateau, a subsea formation to the east of Luzon, the Philippines main island (Philippine Star, March 29). However, less than a week later Duterte rolled back these comments “Because of our friendship with China” (ABS-CBN News [Philippines], April 12). Earlier in March Duterte had declared that he did not wish to confront China in the South China Sea and that “”I deeply believe the Philippines-China relations will scale new heights” (Xinhua, March 17).

Despite winning a judgement against Chinese occupation of islands in the South China Sea before the international court of arbitration in July 2016, Duterte, then newly elected, put the Philippines on a path toward closer relations with China. Most importantly, he also appears to have adopted many of China’s attitudes toward economic and strategic issues.

The Philippines are an interesting test case for the effectiveness of Chinese attempts to export values and win allies through economic incentives—even those with whom it has competing territorial claims.

During his October 2016 state visit to China, Duterte secured $24 billion worth of loans and infrastructure projects (China Brief, November 11, 2016). Economic development is a core plank of Duterte’s political appeal, one he is unlikely to risk through real action in the South China Sea. Moreover, his desire for better relations with China appears to go beyond a need for investment. During his meeting with CCP Liaison Department Head Song Tao (宋涛), Duterte expressed admiration for the CCP’s governance of China, saying he wished to send members of his PDP–Laban political party to China to learn (Guangming Daily, February 24). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Duterte’s national security policy appears to at least “rhyme” with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “Comprehensive National Security Outlook” (总体安全观).

Duterte’s “National Security Policy 2017–2022”, proposed in October 2016, places internal conflicts (Moro secessionism and the communist insurgency), economic and social threats, poverty, corruption, drugs, food security) as its focus—not external security (Manila Bulletin, March 14). [1] Fiery rhetoric about improving bases aside, budgetary figures indicate that the focus will be on these internal economic and security issues—not confrontation with China (Rappler, January 21).

A pronounced realignment of resources toward internal security will have long-term negative consequences for the Philippine Armed Forces’ ability to challenge Chinese intrusions. A recurring problem with Philippine assertiveness is not just the tremendous imbalance in Filipino vs Chinese military capabilities (for example, the PLA Navy’s 9th Zhidui, homeported in Sanya, Hainan province, has more firepower than the entire Philippine Navy) but also in terms of maritime and aerial surveillance. If possession is nine-tenths of the law, then being able to monitor airspace and ship traffic is its maritime equivalent.

The features and islands that the Philippines occupy in many cases lack proper facilities. A handful of Philippine Marines live in the BRP Sierra Madre, a 1940s-era ship run aground on Ayungin Shoal (Second Thomas Shoal). Pag-asa Island, for example, has a short unpaved airstrip, barely capable of handling C-130 transport planes. The largest occupied island in the Kalayaan municipality, it is home to less than 200 full-time residents. Palawan, the long and narrow island further east, was planned to be the home to an expanded U.S. presence.

“Flight Plan 2028”, an overview of the Philippine Air Forces’ modernization plans, which was drafted under previous President Benigno Aquino anticipates extending the Philippines’ Air Defense Identification Zone to adequately cover the country’s Exclusive Economic Zone and claims taking until 2028. Current radars and interception capabilities are insufficient to cover even the majority of Philippine territory, and most of the radars date to the 1960s (see map). [2]

For Duterte, backing down on territorial claims could mean that his government misses out on major economic windfalls. In addition to its importance for fishing, one contended area, Reed Bank is believed to have 115 million barrels of oil and 4.6 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (Manila Bulletin, November 20, 2016).

Given the Philippines economic problems (12 million Filipinos live in extreme poverty), such a “guns vs butter” calculation is incredibly difficult (Philippine Daily Inquirer, March 18, 2016). Even Duterte’s predecessor, President Benigno Aquino backed off some aspects of his ambitious modernization program, noting that for the cost of a single fighter jet, the government could build 2,000 classrooms (Philippine Star, July 22, 2013). Duterte’s acceptance of Chinese investment in exchange for not challenging territorial claims has important security implications for the rest of Southeast Asia.

President Duterte has clearly changed the direction of Philippine defense policy, prioritizing achieving internal security and economic prosperity first. However, with Chinese island reclamation projects nearing completion, and expanded U.S. access to Philippine facilities uncertain, Duterte may have traded away the Philippines ability to effectively enforce their claims. It also sets a precedent for other states which face similar hard choices: improve defenses and bring China to the negotiation table over territorial claims, or accept economic investment for acquiescence.

Peter Wood is the Editor of China Brief. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterWood_PDW

Notes

- National Security Council Secretariat, Briefing: “Our National Security Policy For Change and Filipinos Well-Being (2017-2022), October 7, 2016.

- Philippine Air Force “Flight Plan 2028”, December 17, 2014.