Blinding the Enemy: How the PRC Prepares for Radar Countermeasures

Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 6

By:

Information warfare and information operations constitute the foundation of the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) doctrine of winning what it calls “informationized wars (信息化战争).” [1] Electronic warfare (EW), one of five pillars of information warfare, has found its way to the forefront of the PLA’s war preparation agenda. All PLA major exercises now feature significant EW components.

These developments have real-world implications: In late January, PRC media unveiled a new type of airborne jamming system mounted on Xi’an H-6G long-range heavy bombers, trumpeting its role in reinforcing PRC electromagnetic spectrum dominance in the South China Sea (Huanqiu Net, January 24). The muscle flexing shows growing PRC confidence in EW technology and widening EW capability gap between the PRC and its neighbors.

Despite all this, the PLA’s EW capacity has been a neglected topic, primarily because of the lack of quality information. However, new sources, examined here for the first time in English-language PLA analysis, allow us a unique look at previously unexamined subjects. For the purposes of simplicity, this paper leaves aside issues such as sensors, communications equipment, and weapons systems to focus on one facet of EW, namely, how the PRC conceptualizes and prepares for radar countermeasure (RCM; 雷达对抗) [2]. Indispensable to modern wars, the “blinding” of enemy radars with EW complexes provides friendly forces a critical edge in combat. Therefore, the PLA thinking illuminated by the main text of analysis, including simulations of strikes against enemy carrier battle groups, deserves in-depth examination and assessment.

The Text to Be Analyzed

The bulk of this paper’s analysis draws from the Principles of Radar Countermeasure (雷达对抗原理), hereafter called Principles. Funded by the Central Military Commission’s Project 2110 and published by the PRC’s National Defense Industry Press, the book was last updated and reprinted in November 2016. The text is a collective effort of the PRC’s top radar and EW experts from the National University of Defense Technology’s Electronic Countermeasure Institute and all five PLA branches.

Based on the Electronic Countermeasure Institute’s internal textbooks, Principles reveals how RCM is taught in leading PRC EW schools and how PRC thinkers conceptualize RCM. Thus, we can say with confidence that Principles is an authoritative text with reliable information on the subject, one that allows us to treat the subject in much greater depth than has previously been the case in authoritative, open-source English-language publications. [3]

Differences in PRC and US Perceptions of EW

It is important to note that the PRC is learning quickly from the US in EW matters. PRC thinkers keep a very close watch for new ideas coming out of its number one competitor—the US. At a recent Qian Xuesen Forum that saw the gathering of leading PLA-affiliated scientists and engineers, an expert with the PLA’s Strategic Support Force delivered a speech on artificial intelligence and electromagnetic spectrum warfare, an expansion of current EW concepts first publicized in 2015 that has yet to be fully embraced by the Pentagon (81IT Net, February 22).

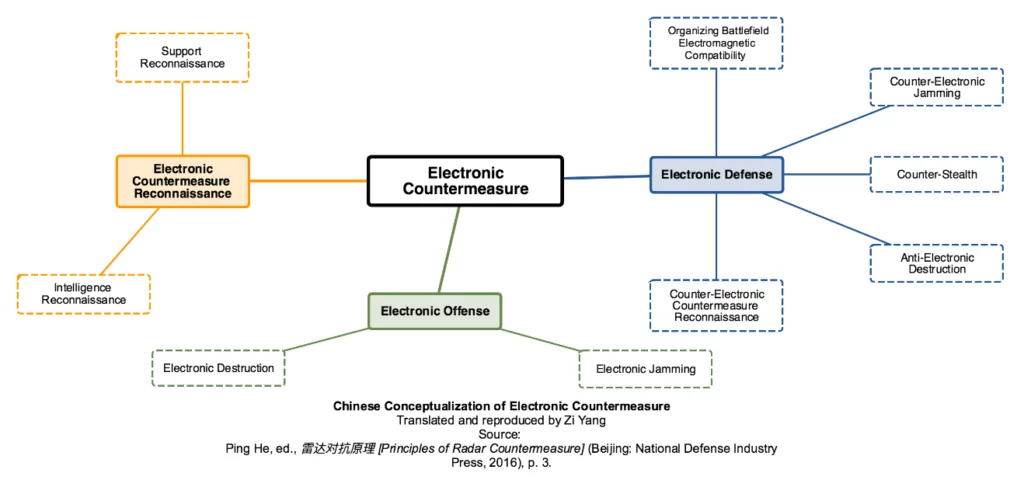

Perhaps because of this, while PRC and American thinkers use different terminology to describe various aspects of EW, their concepts largely overlap. US experts subdivide EW into three areas: electronic support, electronic attack, and electronic protection. In Chinese jargon, these three are respectively called electronic countermeasure reconnaissance (电子对抗侦察), electronic offense (电子进攻), and electronic defense (电子防御) (Principles, pp. 2–3).

There are two key differences to note: Firstly, the Chinese jargon “target electronic protection (目标电子防护)” refers specifically to target protection, while the American term “electronic protection” covers a much broader area. Secondly, Americans view jamming and deception as two distinct concepts, while PRC experts see them as an integrated whole (Principles, p. 3–4).

The Chinese term for EW is “electronic countermeasure (电子对抗).” RCM is further defined as “a form of electronic countermeasure aimed at protecting friendly radars and undermining/damaging the effectiveness of enemy radars (including radar countermeasure equipment) (Principles, p. 4).”

PRC Views on RCM “Hard Kills”

Hard-kill refers to the substantive destruction of enemy assets. PRC thinkers view anti-radiation missiles, drones, bombs, and high-power microwave weapons as the main tools of trade in the substantive destruction of enemy radar systems. Principles describe in some detail the pros and cons of each of these methods, as well as how they are to be used in combat.

Anti-radiation missiles (ARMs) normally employ passive radar homing. The blast radius of an ARM is generally 20 to 60 meters. ARMs are typically highly stealthy and intelligent, but some are limited in their capabilities by their passive radar seekers. The PRC has four types of ARMs—the CM-103, YJ-91, LD-10, and FT-2000 (National Interest, November 30, 2017). Of these the FT-2000 is perhaps the most noteworthy. It is a unique surface-to-air ARM made to target airborne early warning and control aircrafts and EW aircrafts. Cold launched, the FT-2000 utilizes active radar homing to strike targets 12 to 100 kilometers away, at altitudes of between three and 20 kilometers (China Net, August 21, 2015).

Usually weighing 200 kilograms or under, anti-radiation drones (ARD) conduct kamikaze attacks on its intended target. The blast radius of an ARD is larger than an ARM at 50 to 100 meters. The ARD’s greatest advantage is that it can be used as a loitering munition (Principles, pp. 241–243). In a military parade in August 2017 at Zhurihe Combined Tactics Training Base (朱日和合同战术训练基地), one of the PLA’s main training bases, the PLA demonstrated its ASN-301 ARDs. Bearing striking resemblance to the Israeli Harpy, the ASN-301 has a range of 288 kilometers, a destructive range of 20 meters, and four hours of endurance (Israel Defense, March 1, 2017).

Although anti-radiation bombs (ARBs) are discussed in Principles, the authors admitted that it is rarely used in combat because to do so requires air superiority.

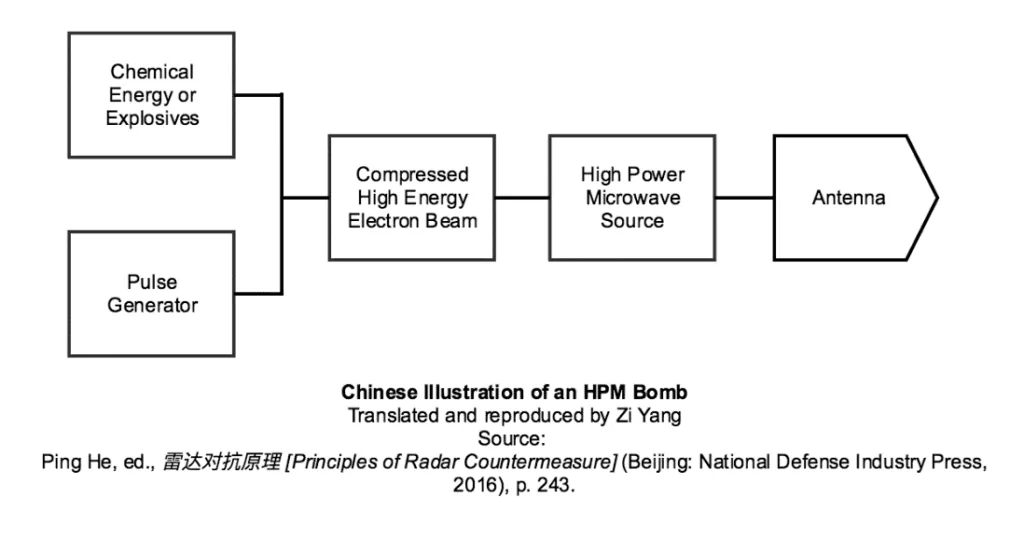

High-power microwave (HPM) weapons, although not yet fielded, are in the view of PRC experts a critical future EW weapon. HPM pulses enter electronic equipment through the “front” (antennas) and “back” channels (any openings on the target) (Principles, p. 244). Depending on radiation intensity, HPMs can disable or completely destroy enemy electronic equipment.

HPMs can also harm human radar operators. At low intensity (3–13 milliwatt/cm2), HPMs can cause confusion, memory loss, altered behavior, blindness, deafness, loss of consciousness, and even heart failure. At the highest level of intensity (80 watt/cm2), a HPM attack would be a “death ray”, killing enemy combatants within a second (Principles, p. 245–246).

The authors of Principles seem to have more information on miniaturized HPM bombs—deliverable via artillery shells, rockets, aerial bombs, and missiles—than they do on HPM weapon complexes—which could indicate Chinese technological maturity in the former, or an attempt to conceal advancements in the latter. [4]

PRC Views on RCM “Soft Kills”

Soft-kill refers to the use of EW countermeasures to disrupt and confuse the enemy. Principles outlines two types of radar jamming: suppressive and deceptive. Each topic has an active and passive side, as well as further subdivisions that yield a dozen or more distinct jamming techniques.

Active suppressive jamming uses noise or pulses to overwhelm and interfere with the operation of enemy radar receivers. One example among dozens of jamming techniques is random pulse jamming, which employs pulses with irregular parameters to cover the radar echoes bouncing off a target (Principles, p. 167). Passive suppressive jamming refers to the use of chaff and corner reflectors on the physical battlefield.

Deceptive jamming uses false signals to mislead enemy radars. So-called “active deceptive jamming (有源欺骗性干扰)” also has a range of techniques. Ground bounce jamming, for example, is most effective against active or semi-active homing missiles. In this scenario, an airborne EW system projects a powerful simulated radar echo at the ground, in such a way that it is reflected towards the incoming missile. If successful, the missile will instead home in on the simulated echo (Principles, p. 198). Passive deceptive jamming refers to decoys such as drones and rocket-propelled decoys. The radar cross-section of decoys must be more reflective than that of the real target, but not overly strong, or else it would increase the risk of the decoy getting exposed.

PRC Views of RCM’s Defensive Aspects

According to Principles, the most important ways to guard friendly assets against enemy radars are disguise and stealth. It also divides these techniques into ‘natural’ and ‘man-made’.

For example, the Principles point out, the earth’s curvature creates radar blind spots that allow friendly assets to position themselves out of sight of enemy radar. Rough terrain such as forests, mountains, hills, and valleys can also hide friendly assets, while rain can degrade radar echoes (Principles, pp. 219–221). However, natural disguises are not the best option since they are not always readily available.

Multi-spectral camouflage is a convenient tool for protecting friendly assets from radar detection. But if this is unavailable, Principles suggested that tree branches, reeds, and hay could be utilized, although they must be sufficiently thick to deflect electromagnetic waves (Principles, pp. 222–223).

Stealth technology, on the other hand, focuses on reducing radar cross-sections through smooth exterior design that minimizes corners and edges.

In addition to passive measures, the Principles suggest a self-screening jammer can mask the target through jamming the main beam of enemy radar.

To defend against anti-radiation weapons, Principles suggests the use of decoys and deceptive jamming to confuse the incoming weapons or trigger a premature detonation (Principles, p. 255). Specific to HPM weapons, Principles advocates adding a filter system for incoming microwaves, the use of burn-resistant materials for electronics, adding an automatic shutdown mechanism that anticipates an HPM attack, and sealing or lining all openings on equipment with HPM-absorbing materials (Principles, pp. 257–259).

Putting It All Together

Towards the end of the book, Principles features a series of RCM simulations that reveal PRC thinking about how the various RCM tools and techniques illustrated above could be integrated on the tactical level. However, it is necessary to note that these examples are based on PLA observations of foreign military exercises and simulations.

One case with considerable relevance to a future conflict in the Asia-Pacific is a simulated airstrike on a carrier battle group.

The attacker consists of over 20 aircraft enhanced with EW countermeasures—16 bombers, one early warning and control aircraft, one RCM support aircraft, three airborne standoff jammers, and two EW aircrafts loaded with ARMs.

The attack begins with the RCM jet identifying and locating enemy radar. This information is then passed on to the entire attacking formation. Three standoff jammers begin to disrupt the carrier battle group’s radar. Two EW jets then attack enemy radars with ARMs, while lead bombers lay down chaff corridors to shield friendly bombers as they approach the target. The self-screening jammer on each bomber is simultaneously activated.

As the bombers approach the target, the chaff dispensers make a sharp turn. Bombers begin attacking the enemy with precision-guided munitions. Friendly standoff jammers then shift their focus to jamming enemy fire control radars, missile guidance receivers, surveillance radars, and command guidance links, until the attack is over (Principles, pp. 282–283).

The simulation projects the entire attack to last between 10 to 15 minutes.

Conclusion

Compared to emerging EW powers like Russia (ICDS, September 2017), we know far too little about China’s actual EW/RCM capabilities. Against the backdrop of China’s strict information control regime, what we can extrapolate from Principles gives us a much-needed glimpse into how China conceptualizes RCM and how it educates its EW specialists. This brief overview and analysis has not covered Principles in its entirety; interested readers would do well to consult it for a comprehensive, authoritative look at how the PLA conceptualizes RCM as part of its overall EW doctrine.

Zi Yang is a Senior Analyst at the China Programme, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Follow him on Twitter @ZiYangResearch.

Notes

[1] According to Heritage Foundation’s Dean Cheng, “The PLA’s 2011 volume on terminology describes ‘informationized warfare’ as warfare where there are networked information systems and widespread use of informationized weapons and equipment, all employed together in joint operations in the land, sea, air, outer space, and electromagnetic domains, as well as the cognitive arena. In informationized warfare, the main form of conflict is between systems of systems. As part of this systems-of-systems construct, informationized warfare is envisioned as informationized militaries, operating through networked combat systems, command-and-control systems and logistics and support systems.” See: Dean Cheng, Cyber Dragon: Inside China’s Information Warfare and Cyber Operations (Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 2016), p. 39.

[2] Radar countermeasure (雷达对抗), communications countermeasure (通信对抗), electro-optical countermeasure (光电对抗), and underwater acoustics countermeasure (水声对抗) constitute the four subsets of Chinese EW or dianzi duikang (电子对抗).

[3] Even the Pentagon’s annual reports on the PRC military capacity, typically one of the most authoritative, in-depth sources available, have had relatively little to say on this subject. For the interested reader, the annual report’s most extensive treatment of PRC EW to date can be found on page 66 of the 2014 annual report.

[4] For the latest developments on Chinese HPM weapons, see: The Diplomat, March 11, 2017.